Reviews

Preppie! II

Adventure International

Longwood, FL

16K Cassette

32K Diskette

$34.95

by Steve Harding

Up and coming prepster Wadsworth Overcash had the world by the tail until a failed Freshman initiation banished him to the tender mercies of the cruel Groundskeeper. Forced to recover wayward golf balls on a course of hellish design, Wadsworth barely escaped with his Lacoste intact. Now, the saga of Wadsworth Overcash continues as he faces his greatest challenge yet in -- Preppie! II" So begins the manual in the latest installment in Russ Wetmore's delightful Preppie! series from Adventure International.

Preppie! II is far different from Preppie!. In Preppie! II, our hero finds himself once more in the clutches of the evil Groundskeeper. This time, the golf ball retrieval motif has given way to a paintbrush, and a plethora of "Preppish" colors with which Wadsworth must paint the floor throughout a series of mazes. There are five levels with three different mazes in each level. The object is to paint the entire floor in each of the three mazes.

Sounds easy so far, right? Not so. The first and third maze in each level are inhabited by radioactive frogs that will search out our hero and leap on him, given a chance. Each of these mazes also has a pair of revolving doors that Wadsworth can use and the frogs can't -- a real advantage for our hero, unless there happens to be a frog waiting on the other side!

|

| Preppie II |

The middle maze in each level should look familiar to Preppie! veterans. The lawn mowers and the golf carts are once again out in force in an attempt to "raze" Wadsworth's hopes. These mechanized dangers move horizontally and at varying speeds, making avoiding them all the more difficult.

Wadsworth has one advantage -- The Cloak Effect. Pushing the joystick fire-button renders him invisible for a short length of time. The Cloak Effect also makes our hero impervious to radioactive frogs, lawn mowers and golf carts. The amount of Cloak Effect available is shown by a bar at the bottom of the playfield. But use the Cloak Effect sparingly and only when you've painted yourself into a corner. Once the Cloak Effect is gone you're on your own until the next game.

Russ Wetmore has provided a little cartoon respite between the first and second levels: an alligator chasing Wadsworth across the screen. Then Overcash, swinging a hammer, chases the alligator. As for other between-level surprises, you'll have to discover them for yourself. Level three is as far as I can go for now.

Mark Murley's documentation is almost worth the program's suggested retail price of $34.95. It is well written and humorous. You can play the game without reading the manual, but do read it. It's quite good.

In sum, Adventure International and Wetmore are to be commended for a job well done. I can hardly wait for Preppie! III!

Chess 7.0

by Larry Atkin

Odesta Corp.

Evanston, IL

48K Disk

$69.95

by Murray D. Kucherawy

"Chess, like a beautiful woman, has the power to make men happy." - Tarrasch

For most chess players computerized games are disappointing. The principle reason is that a challenging mental game requires a lot of time.

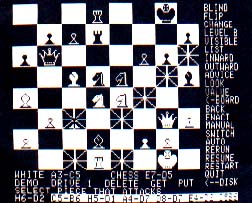

|

| Chess |

Most computer chess games reflect that time in their lack of speed. Such lack is understandable since a programmer is faced with nearly unlimited possibilities in the first 10 moves of a chess game.

One of the latest efforts is Chess 7.0 from Odesta Corp., which shows improvements in time delays and has other chess "goodies." You can challenge your computer at any one of the 15 skill levels -- some of which are "thinking-time limited" levels and others which are "depth-of-search limited."

Chess 7.0 thinks about its next move while you're thinking about yours. If your move was expected by the program, the response is quite fast and, if you're impatient, you can hit return and Chess 7.0 will respond with the best move it has found so far.

The author of Chess 7.0, Larry Atkin, is a member of the programming team that produced the famous and very successful Northwestern University chess programs, which have won several international computer chess championships. They also have placed highly in tournaments where they played against humans.

I have a secret test I apply to chess programs to determine how strong they are. Several years ago I played in a tournament in which I spotted an intriguing possibility involving the sacrifice of my knight. I studied the position intently and finally made the sacrifice. A few moves later I won the game. There was controversy afterward as to whether I really had won or my opponent had simply been unnerved and then had blundered. Nonetheless, I was awarded the "brilliancy" prize for the tournament.

After that, whenever I wanted to test the playing strength of a program, I would--behind closed doors--set up the position, make my sacrifice and see what the computer would do.

I applied this test to Chess 7.0. Modesty keeps me from discussing the results, but that Chess 7.0 has my respect.

In this chess-playing game, which will provide years of enjoyment for any chess player, there are several built-in functions that make Chess 7.0 a teacher as well as an opponent.

It plays the opening moves by referring to its internal "library" -- a stored collection of moves and responses which have become recognized as strong openings through decades of tournament play. There remains a random element in move selection so each game will be unique.

If you're stumped for a move, you can ask for advice and, at most levels, Chess 7.0 will make a suggestion. It also will show you what move it will make if you take its advice. If you ignore its advice and blunder, the program allows you to take back the move (or any number of moves right back to the beginning of the game). You also can peek at what move the program is considering for itself in any position.

Think you're winning? Call up the value function which will display a positive or negative number. Positive means Chess 7.0 has the advantage while negative means you're ahead and the size of the number indicates how strong the advantage is. You may see "MT3", meaning you will be mated in three moves.

Has your wife called you for dinner for the third time? You can save your game to disk. Got a losing position? You can switch sides with the computer. Want to play with a friend? You can use the chessboard on screen and Chess 7.0 will be the referee watching for illegal moves on either side, ready to take over for either player. This feature is also handy for studying the instructive games published in chess columns and magazines.

A very attractive and complete manual is included in this package. Not only is each option explained in detail, but rules, strategy and lore are discussed for the benefit of the novice.

In summary, this is a superlative product surpassing all current chess-playing programs available for microcomputers in speed, playing strength and versatility.

Flip Flop

by First Star Software

New York, New York

Atari 400/800/1200 Disk

$29.95

by Mark S. Murley

Game concepts, like hemlines, rise and fall with fadish regularity. Three years ago, horizontal scrolling hit the coin-op market like a right cross from Mr. T. Then, somewhere at a stockholders' meeting, some corporate demagogue must have leaped from his chair and cried: "Hey, there are girls out there with quarters, too! Gimme cute!" Thus, PacMan, Centipede, Donkey Kong, and other basically non-violent games were birthed. The cutesy approach to video gaming was in full swing.

|

| Flip Flop |

Now, the 3-D look is in. If you don't believe that, grab your calculator, saunter down to the corner arcade and start counting the coin-ops that at least go through the motions of a 3-D look and feel. Zaxxon, Sub-Roc 3-D, Buck Rogers, and Star Wars are a few that I can think of.

Of course, the promise of true three dimensional graphics on your home computer is sham. What they're doing is shifting the perspective, in much the same manner that you can draw a square from an angle and give the appearance of depth. It's a nice change of pace, though, and there are a few games currently on the market that milk the shifted-perspective cow rather well. Which brings us to Flip Flop, from First Star Software.

First impressions stick, and the first impression one gets upon seeing Flip Flop is that the guy who designed it probably spent his summer vacation stuffing quarters into a Q*Bert coin-op. But before you sneer, consider the recipe which was prepared so effectively by Preppie! author Russ Wetmore: Take the basics to one proven arcade game (Frogger), add a liberal reworking of the theme, and garnish generously with originality. Voila! One surefire hit.

The action in Flip Flop takes place on what the game instruction card refers to as the "Zoo of the Future." It's a multi-tiered chessboard of sorts, with the player's perspective being one of looking down slightly at things. Each tier, or platform, may be accessed by small ladders, and contains a number of "good" squares and one or two "magnetic" squares, called sticky squares.

Your link to the game is Flip, a joystick-directed kangaroo who will leap obediently at a touch of the joystick handle. Like Q*Bert, the idea is to cover the good ground while avoiding any random dangers that may be out and about. Unlike Q*Bert, there are certain squares which should be avoided. Hop on each of the good squares and you'll advance to the next -- and more difficult -- level. Land on one of the sticky squares and you'll be held in check for several seconds.

The most subtle danger in Flip Flop is one of simple slippage: failure to maneuver Flip just so may result in a nasty fall from the relative safety of the playing board into open space. More obvious threats are the Zoo keeper and his flying net. This latter menace appears from level three on, and looks something like a screen door run amuck. Despite its simple appearance, the flying net is a merciless little cuss, and it can put a hurtin' on those high-score hopes toot sweet.

You begin each game with an allotment of five critters (called "tries" in the game's instruction card), and earn an extra one with each level completed. Considering the dangers that are prevalent, it may not be too long before you'll be wishing for another 'roo or two. But gee, Dad, why do they call it Flip Flop? Well, son, it's like this...

Sometime during the game design process, someone (Steve Martin is a safe bet, although it was probably the program's author) thought it would be a laff riot to turn the entire playing board upside down at certain points in the game, so the player is looking up at, rather than down on, the playing board. Funny thing is, the topsy-turvey schtick is a laff riot, but it also adds immeasurably to the game itself.

Of course, no self-respecting kangaroo would be caught dead loitering Down Under such a contraption. Exit kangaroo, enter one honest-to-Bonzo swinging ape, named Mitch. The basic play idea is still in effect -- to touch all of the good squares and avoid falling or tangling with one of the deadly screen doors. But this time, you're doing it upside-down, for cripe's sake. The effect is quite marvelous, though somewhat unsettling the first two or three hundred times you experience it. Lest Mitch wear out his welcome, he alternates turns with Flip.

Any game that boasts 36 playing levels needs something to break up the monotony. Flip Flop scores admirably on this account by treating the player to some cute between-levels animation. These cartoon intermissions appear after five levels are successfully completed. In the true Lassie-you've-come-home! fashion, Flip and Mitch are shown having accomplished the true goal of Flip Flop: a reunion with their friends back at the circus. It's enough to bring tears to your eyes.

There's quite a bit more to Flip Flop, including a running clock you have to race against; double maze patterns, the squares of which require a second visit to score; and the strategy side of the game, which includes buying time by "tricking" the Zookeeper or his flying net onto a sticky square.

The standard space shoot-em-ups and generally poor rip-offs are in such overwhelming abundance that I was tempted to give Flip Flop a B on this quiz without so much as having seen a single pixel. But after spending several evenings with the game, I'm happy to report that Flip Flop has earned a solid A -- solely upon its own merits. The game is visually sharp, the sounds and musical accompaniment complement rather than detract from the visuals (are all of you programmers-cum-Mozarts listening out there?), and the upside-down angle offsets any potential playing tedium. Flip Flop looks and plays well. And that's good enough for me.

Bandits

Sirius Software

Sacramento, CA

800/1200 Disk

$34.95

by Duane Tutaj

An arcade-type space shoot-em-up game for the Atari, Bandits is 100% machine language and the graphics displays are very well done. Bandits requires one joystick and is a single player game.

The object of the game is the time-tested arcade theme: shoot down various space ships or bombs while avoiding being hit by return fire. If an enemy ship survives your fire and reaches the right side of the screen, they will take a portion of your supplies and try to escape to their mother ship, which is located in the upper left-hand portion of the screen. Shooting the enemy while they are carrying your supplies will score more points and return your supplies. You have five packages of supplies in each of the 28 different levels. If the enemy manages to steal all five packages at a given level, the game is over. Bonus points, based on the amount of supplie's that you have left, are awarded for clearing the screen of enemy ships.

|

| Bandits |

You start the game with five ships of your own and receive an additional ship for every 5,000 points scored. Your greatest defense is an energy shield that is activated by pushing up on the joystick. Repeated pushes will give you the longest shield life. Whenever you lose a ship, your shields can be recharged to their maximum levels. The game can be paused by pushing any key and reactivated with a second key press -- an important feature for anyone surviving several levels of play and needing a bit of non-penalized respite. The good news is that the high score is updated after every game. The bad news: the score cannot be saved on your disk.

One of the more positive aspects of Bandits is the graphics. They're quite impressive, especially the fast movement of the various enemy ships. The use of different types of supply items adds color to the game and helps one in determining the current level. The sound effects provide a similar function; allowing the player to distinguish between the different types of enemy ships.

To use the familiar "10" scale, I would rate Bandits as follows: Concept-7, Graphics-8, Sound-5, Playability-7, Overall-7. All in all, a modest and reasonably enjoyable effort by Sirius.

Sirius will replace a defective disk for only $5.00 with the return on the original. Hopefully, more software houses will start having reasonable replacement policies.

The screen displays a planet surface with a crater on each side. The right hand side is a portion of a moon that shows your supplies. In the upper left-hand portion of the screen is the bottom of the enemy mother ship through which the enemy attacks and returns with the loot. At the top of the screen is the scoring display which shows your current score, the high score, and the number of remaining ships. While the game is in progress, stars scroll across the screen at varying rates of speed to add to the illusion of movement.

Your ship is located on the planet's surface and moves side to side in true Space Invaders fashion, while shooting up at the attackers. At the bottom of the screen is a gauge that monitors the energy left in your shields. Wise players will turn their shields on and off during play to save power for the longest possible protection. Fortunately, competence has its own reward: your depleted energy will recharge slowly while you avoid the enemy attacks.

What makes Bandits different from most shoot-em-up-style games are the various combinations of enemy ships that attack. One type of ship is shaped like a rubber ball; it will cascade down on you and continue bouncing up and down off the bottom screen until destroyed. Another unusual ship looks a bit like a centipede and drops napalm bombs. Also, there is the ever-threatening Menace that fades in and out and attacks swiftly.

One important fact about each level is the combination of various enemy ships and the amounts of each ship is different for each level. This means it's possible to be facing elements from several of the most common types of arcade games at one time. This short delay is the one negative part of the whole game. After very fast playing action, it is frustrating to wait up to 20 seconds to see what the next level brings. (Perhaps on the higher levels this wait can be restful and needed to refresh your reflexes, but at the first few levels it really slows down the action.) I feel that a multiple-player option would have been an exciting addition to this game.

B.C.'s Quest for Tires Review

by Reid Nicholson,

age 11

B.C.'s Quest for Tires you could say is for the Donkey Kong type of player in the family for in this game you hop on your prehistoric one-wheeler and dodge prehistoric obstacles to save the beautiful girl from the hungry dinosaur.

On the way some of the obstacles you have to dodge are tiny holes and boulders, a fat broad, trees, volcanos and other prehistoric things.

The joystick usage is perfect and the graphics for this game are just as good as the cartoon B.C.

All around you could say that B.C.'s Quest for Tires is the prehistoric home Donkey Kong type of game we've all been waiting for.

The Dark Crystal

by Sierra On-Line

Coarsegold, CA

Atari 400/800/1200

48K Disk

$37.95

by Mark S. Murley

December 1982 saw the release of one of the most anticipated and esoteric films in recent memory: master puppeteer Jim Henson's epic, "The Dark Crystal." Five years and a reported $26 million in the making, this fantasy adventure tapped the talents of literally hundreds of technical personnel to bring an elaborately constructed universe of characters to life.

Unfortunately, after a brief flare of interest, the audiences stayed away in droves. And the critics, while praising the puppet artistry and attention to minutiae, shook an unforgiving finger at Henson for the film's lack of thematic focus and the inability of the puppets to adequately convey emotion. As reviewer Allen Malmquist wrote in Cinefantastique magazine, "For the love of puppetry, 'The Dark Crystal' succeeds, and for the love of puppetry, 'The Dark Crystal' fails."

But in spite of its flaws, "The Dark Crystal" did create a visually exciting and compelling world; a world populated with dozens of strange and wonderful creatures, and more importantly, a world with a Mythos. Watching the film may not have given one the total sense of involvement that Henson and his associates were shooting for, but neither did one leave the theater with feelings of deja vu: "The Dark Crystal" was truly a groundbreaking motion picture.

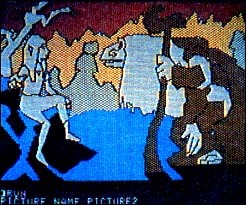

|

| Dark Crystal |

The Next Big Film, as everyone knows, is always dogged by enough tie-ins to fill every Toys'R'Us in New Jersey. "The Dark Crystal" was no exception. Last Christmas saw a full complement of "Dark Crystal" books, posters, toys, stationary, and, if one probably looked long enough, underwear. It is my understanding that Henson himself had some control over what was marketed, which would account for the solid quality of some of the items I've run across. Into this category fall several books that chronicle the film's making from preproduction to the final print. Another is the officially sanctioned Adventure game for the Atari home computer, from the folks at Sierra On-Line.

The Dark Crystal, as presented by Sierra, is the latest in their continuing line of Adventure games, and their first motion picture tie-in. The Dark Crystal, the game, aspires to the same lofty heights as does the film, and comes not on one, but three double-sided disks. The package itself is a handsome, 8 1/2 by 11 inch, 12-page glossy booklet that features the plot synopsis, map-making and hint sections, and a few empty pages for your notes all printed on thick, parchment stock. Also included is a full color, 17-by-22 inch poster which depicts Jen at the triumphant climax of the movie.

For those of you who haven't seen the film, here's the Reader's Digest condensed version.

Somewhere on the far side of the universe, a spectacle which occurs only once every millennium is about to take place: The Great Conjunction of the planet's three suns. So powerful is this cosmic happening that the urSeks, a gentle race of philosopher beings, have journeyed from their home planet to this world in preparation for the event.

The urSeks proceed to construct a place of worship around the Crystal, which is a large, mystical energy conduit of sorts that can amplify the power of the Great Conjunction to an unlimited degree. The ultimate goal of the urSeks is to use the energy of the Crystal and the Great Conjunction to purge the urSeks' evil sides into non-existence, leaving only that which is perfect.

At the moment of the Great Conjunction, the UrSeks entered the blinding beam of light produced by the Crystal. Each urSek entered as a single being, but exited as two separate races of entities: the hideously repulsive Skeksis and the gentle Mystics. Immediately a brawl between the two factions erupted, and the Crystal was damaged, sending a crucial shard flying out somewhere into the surrounding countryside, lost.

The schism complete, the Mystics abandoned the castle to the Skeksis, and fled to the Valley of the Stones. It was in this place that the Mystics regrouped and began working their largely impotent magic against the Skeksis' growing tide of evil.

Eventually, the Skeksis saw fit to exterminate a third race of beings, the Gelflings. But two infant Gelflings, Jen and Kira, survived the slaughter and were raised by the Mystics and the Pod People respectively. And it is Jen and Kira who have the task of restoring the missing shard to the now-darkened Crystal -- an act which will end the reign of the Skeksis forever and restore Harmony to all things.

To paraphrase Malmquist's opinion of The Dark Crystal's cinematic counterpart, for the love of ambition, The Dark Crystal succeeds, and for the love of ambition, The Dark Crystal fails. The Dark Crystal scores big points in whittling Henson's "The Dark Crystal" down to small-screen, home-computer size, but an Adventure of this size is either going to be very linear (to expedite the storyline and prevent pointless "sight-seeing" excursions by the player) or it is going to mire down like a bloated dinosaur in a primordial swamp of endless details, ending up as entertainment only for Mensa Society members.

The Dark Crystal opts for the linear route, leaving one with the impression that each response typed is either right or wrong, with no middle ground. For the novice, this isn't necessarily a bad thing, but anyone who likes their Adventuring on the, uh, adventurous side may find some difficulty with The Dark Crystal.

The second major complaint with the game involves the three-disk format. No matter how you slice it, swapping disks in and out of a drive can be a real pain, and The Dark Crystal is not equipped to utilize more than a single drive.

If the narrowness of the game and the disk-swapping problem were the only negative aspects of The Dark Crystal, then I might be tempted to at least recommend it, however, to novice Adventurers. The graphics themselves are a little lackluster, and the color is not the best. This is distracting in an Adventure of this scope wherein so much of the player's time is spent looking at dozens of screens.

Sierra On-Line, by in large, has an excellent reputation for quality Adventures. Everyone misses the mark now and then, and fans of Sierra On-Line will undoubtedly come out soon with a sparkling new game to add to their otherwise solid line of hits.

The replacement of the shard by Jen is the common aim of both the film and the Adventure game. However, the film only requires approximately 90 minutes of passive participation to see realization of the goal; the Adventure version may require a month or more of active puzzle solving.

The three-disk format of Sierra's The Dark Crystal Adventure automatically makes it something of an epic in itself. Side A of the first disk contains the standard loader and title screens, leaving the other five sides of disk space exclusively for data storage and retrieval. Happily, Sierra has eschewed any sort of copy protection for all but Side A. This allows the user to make extra copies of the data disks, which can help take the sting out of the occasional disk accident. And a crashed disk can become a nightmare of epic proportions if you've put a lot of sleepless nights into solving the Adventure.

The opening screen of the Adventure finds Jen resting in a forest; we are informed that he is in the Valley of the Stones, which has become the new dwelling place of the benign Mystics. Upon entry of the player's first command, a Mystic approaches Jen with news most grim: urSu, the leader of the Mystics, is dying and that Jen is requested to quickly go to his side. The Mystic disappears, and the Adventure is begun.

It would be cheating to reveal any details about The Dark Crystal beyond this point. Suffice it to say, the Adventure revolves solely around Jen's attempt to locate and restore the shard to its proper place in the Crystal. Along the way, a wide range of strange creatures, places and events will be encountered by Jen and the intrepid Adventurer.

The Dark Crystal religiously follows the typical Adventure format of command entry. You control Jen by inputting commands of one or two words, usually in the verb-noun format. If, for example, one is standing in a forest, one might type GO NORTH to move in a forward direction, or CLIMB TREE if one happens to be standing aside an oak. The true challenge of Adventuring comes from guessing which words work and which don't. Considering the limited vocabulary of most Adventures (usually less than 150 words), this is clearly the most time-consuming aspect of play.

Rally Speedway

by John Anderson

Adventure International

Longwood, FL

Atari 400, 600XL, 800XL, 800,1200

16K Cartridge

$49.95

by Leo G. Laporte

In the beginning there was the driving game. Night Driver. And Night Driver begat Pole Position. And Pole Position begat Turbo. And Turbo begat Rally Speedway. And the smell of gasoline and burning tires filled the sky. And the sound of screeching brakes rent the air. And the players looked down upon the game and saw that it was good.

Sometimes it seems like the driving game has been with us since the beginning of time. Indeed, it is the oldest type of game still popular at home and in the arcades. There are a number of really good ones available for your home computer, including Rally Speedway. Before I discuss the merits of Rally Speedway, though, I'd like to make some observations about driving games in general.

Most of us drive out of necessity, whether we like it or not. Usually the mundanities of everyday life don't make particularly good video games. In the case of driving games, though, the computer gives us a chance to drive the way we would like. Who hasn't wanted to sit behind the wheel, throw caution to the wind and floor the accelerator. For those Walter Mittys among us, the driving game makes a thrilling escape.

Because of this, a sense of speed is important to the driving game. The driver must feel he can control his machine, but he also must be tempted to push his control to the limit, risking life and limb while doing so. The elements of speed and imminent danger always must be present.

For the purist, that sense of speed and risk is enough, but the competition between rival game manufacturers is so intense that each is trying to offer something more in his games.

Rally Speedway, written by John Anderson, follows this trend. It is both a driving game and a track building toy, and even though it's only average as the former, it excels at the latter.

My only criticism of Rally Speedway is in the way Anderson has designed the driving simulation. Most of the driving games I have played and enjoyed give the player a perspective close to the actual driver's. Usually the player sees the road from behind and slightly above his car. This enhances the illusion of speed and makes the game more difficult because of the player's limited field of view. Unfortunately, Rally Speedway is designed so the player looks directly down on the car and road surface, just as you look down on Pac-Man as he traverses the maze.

This perspective diminishes the excitement of playing the game. First-person perspective has contributed to the longevity of the driving games as a class. By changing that perspective, Anderson has eliminated the most compelling reason to play the game.

Having made that criticism, let me say everything else about Rally Speedway is perfect. This is a beautifully designed game. And, to some extent, the challenge of head to head competition compensates for the lack of excitement.

The race is run on a huge track, about 64 screens big. Two different tracks are included with the cartridge. One or two players race around the course. In the one-player version you'll be racing for time; in the two player version you'll be racing for blood.

As you race, the track scrolls smoothly beneath you. If your opponent gets so far ahead of you that he leaves the screen, you'll be assessed a time penalty and both drivers will be repositioned next to each other.

If you go off the road and hit a tree or a building, your car will explode into flames. The little driver will leap out, roll over and over to extinguish his burning clothes and then jump up and wave to signal that he is all right. Then it's back on the road.

There are a number of options that can be selected from a menu before the game. You may choose dry, wet or icy roads. The trees and houses can be real or the type you can drive right through. Your top speed and rate of acceleration can be set, too.

A few extra options make Rally Speedway different from most racing games. These are the LOAD TRAX, MAKE TRAX, and SAVE TRAX commands. Rally Speedway allows you to design your own race track and then save it to disk or cassette. This is the part I found most enjoyable, but then I still like to play with Lincoln Logs.

There are 21 different types of tracks to lay, ranging from straightaways to hairpin turns. There also is an orchard, a lake, three kinds of tree formations and three kinds of houses. You may combine any of these.

The grid is 25 elements square. That's 625 elements to plot, but don't worry, it's not difficult. Everything is done with two joysticks and the function keys. Up to 16 track layouts can be saved on a single disk.

Rally Speedway is graphically gorgeous. The controls are logical and easy to use. The race is challenging, even if it's a bit less than exciting.