The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Defensive Armour and the Weapons and Engines of War of Mediæval Times, and o, by Robert Coltman Clephan This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: The Defensive Armour and the Weapons and Engines of War of Mediæval Times, and of the "Renaissance." Author: Robert Coltman Clephan Release Date: April 5, 2019 [EBook #59209] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK DEFENSIVE ARMOUR, WEAPONS OF WAR *** Produced by deaurider, Charlie Howard, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

Transcriber’s Note

The cover was created by Transcriber, using text and artwork from the orignal book, and placed in the Public Domain.

THE DEFENSIVE ARMOUR AND THE WEAPONS AND ENGINES OF WAR OF MEDIÆVAL TIMES, AND OF THE “RENAISSANCE.”

BY

Robert Coltman Clephan,

OF SOUTHDENE TOWER, GATESHEAD.

With 51 Illustrations from Specimens in his own and in other

English Collections, and also from others in some of

the Great Collections of Europe.

London: Walter Scott, Limited,

PATERNOSTER SQUARE.

1900.

v

This volume has grown out of some “notes” printed in the Archæologia Æliana in 1898, and added to as any new facts and lights presented themselves to me. The text is compressed as much as possible, with a view to publishing at a moderate cost; and as a more general interest in arms and armour is decidedly growing, I venture to hope that this volume, however imperfect, may supply a want, and that it does not contain too many manifest errors and inaccuracies. The subject is treated chronologically, and no further detail entered into than seemed necessary for presenting it in a consecutive and concrete form.

All students, myself among the number, owe much to those experts whose original research and delineation of nice points of detail go to make history in the several branches of my subject, and it is to be regretted that more of them do not undertake further comprehensive work.

Defensive armour is the section I am most conversant with, and it is perhaps the one affording the most concrete materials for chronological classification and analysis.

The question of the weapons of the “middle ages” and of the “renaissance,” their chronology, description and classification, is far from being in a satisfactoryvi state. There are no books dealing with the subject as a whole, and many of the “notes” and “papers” I have seen spread over many years are, most of them, very sectional and fragmentary in their scope and character. Technical terms vary exceedingly among the different writers, and some more generally intelligible codification is very desirable. International it cannot be, as Germany naturally has her own terms, while those of England are perhaps as necessarily mixed up with Norman-French.

There are often great difficulties in the way of reasonably approximating the date and nationality of both weapons and armour, owing to causes which will be touched upon later in these pages; but these apparent inconsistencies must needs be grappled with as far as possible, and herein lies the work of the archæologist. In the case of sword specimens, it very often happens that blades and hilts belong to widely different periods, and even nationalities, and cases of this kind often give rise to much doubt and perplexity; indeed, unless there is evidence that a blade and hilt are contemporaneous, it is always well to consider that they may not be so; for blades were passed down from father to son, and often re-hilted more than once. Hilts also were often re-bladed.

The great question of smiths’ marks could only be adequately dealt with in a volume devoted entirely to that subject. This will be seen from the complexity arising from the piracy of marks—such, for instance, as that of the running wolf of Passau, or Scottish blades with the many variations of “Ferrara” impressed upon them. These marks came to be regarded merely as “standards,” and were often used without any intentionvii to defraud—in the sense, in fact, of the name “Wallsend” being applied to express a certain quality in coals. A book dealing comprehensively with this branch of the subject has yet to be written.

While gratefully acknowledging much information and infinite assistance from other writers, I have found many manifest errors, which have been both inherited and perpetuated, handed down, so to speak, through long generations of book-making. I have taken as little as possible from books, especially over the period where actual specimens are available, but have endeavoured, by carefully studying many important collections, both at home and abroad, to compare, as far as possible, the types and fashions prevailing at the different periods dealt with, which, however, greatly interweave, especially among European nations, where easy facilities for interchange existed.

It takes many years and opportunities of study to achieve much in the direction of judging armour, and it is only by a close comparison, not merely of individual pieces, with a careful examination of every detail, but also a knowledge of the makes of steel of the various ages covered, their composition, manipulation, and relative degrees of hardness, that a reasonable amount of certainty can be arrived at. Much ingenuity has been applied in faking up and partially restoring many suits, still, it is obvious to an expert, in most instances, which pieces are of comparatively modern construction, especially in the cases where ornamentation has been applied, for here the best work of the “renaissance” cannot be adequately reproduced. Many suits, even in national collections, are not only doubtful, but now known to be spurious, while in others the restoration process has leftviii much to be desired. The uninitiated would be surprised if they knew how comparatively few suits are absolutely homogeneous, so many having been set up by dealers, often more or less of pieces of various types and dates.

It is most interesting to trace what may be termed the evolution of arms and armour, and to follow the craft and ingenuity of the armour-smith as pitted against that of the makers of weapons; indeed, all through the history of the armour period this contest has proceeded with varying fortune. Fashion also has always been a potent and arbitrary factor in the direction of change, and hence so many preposterous departures, such as both the extravagantly long and ridiculously wide sollerets of the “Gothic” and “Maximilian” periods respectively. Expansive skirts of steel, which must have been very crippling to the wearers, were used at one time by all cavaliers who had the least pretensions to be considered à la mode.

At the risk of the general subject occasionally overlapping, and of some repetition in matters of historical retrospection, I have concluded to divide these pages into two main sections, viz., “Defensive Armour” and “Weapons of War” over the period set forth in the title-page. This has been done in the interests of conciseness and perspicuity, and more especially with a view to an easy reference to any branch of the subject under discussion.

ROBERT COLTMAN CLEPHAN.

Southdene Tower, Gateshead,

March, 1900.

ix

| PAGE | ||

| Preface | v | |

| SECTION I.—DEFENSIVE ARMOUR. | ||

| PART | ||

| I. | Introductory and General | 15 |

| II. | Chain-mail and Mixed Armour | 20 |

| III. | The Transition Period | 37 |

| IV. | Helms up to the End of the Transition Period | 44 |

| V. | Plate Armour | 48 |

| VI. | A Slight Sketch of some of the more important Collections Abroad | 71 |

| VII. | The Tournament | 76 |

| VIII. | Details of Defensive Plate Armour | 96 |

| IX. | “Gothic” Armour, 1440–1500; and some Armour-smiths of the Period | 114 |

| X. | “Maximilian” Armour, 1500–1540 | 125 |

| XI. | Armour with Lamboys or Bases | 130 |

| XII. | Some Armour-smiths of the first half of the Sixteenth Century | 132 |

| XIII. | Defensive Armour, 1540–1620, and to the End | 134 |

| XIV. | Enriched Armour | 139 |

| SECTION II.—THE WEAPONS AND ENGINES OF WAR.x | ||

| XV. | Introductory and General | 151 |

| XVI. | The Sword | 158 |

| XVII. | The Dagger | 175 |

| XVIII. | The Longbow | 178 |

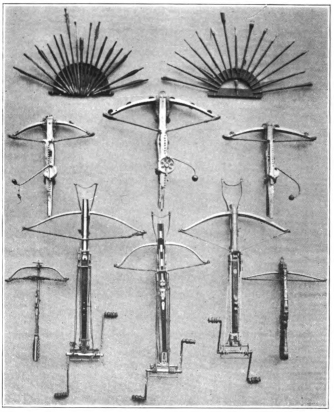

| XIX. | The Crossbow | 183 |

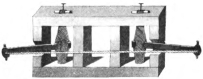

| XX. | Machines for hurling or shooting Missiles, and the Warwolf | 187 |

| XXI. | Machines for attacking Beleaguered Places | 190 |

| XXII. | The Sling and Fustibal | 192 |

| XXIII. | Staff and Club Weapons | 193 |

| XXIV. | Early Artillery | 204 |

| XXV. | Early Hand-guns | 216 |

| Index | 229 | |

xi

| FIG. | PAGE | ||

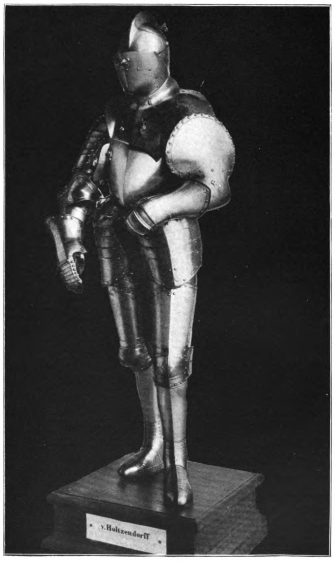

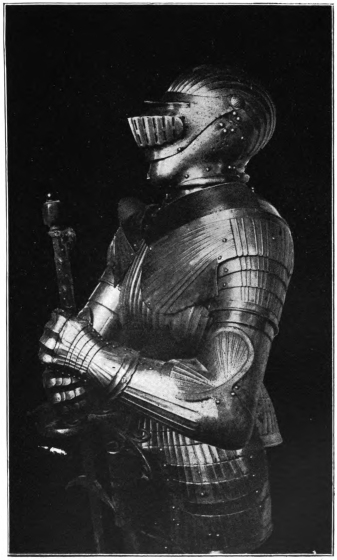

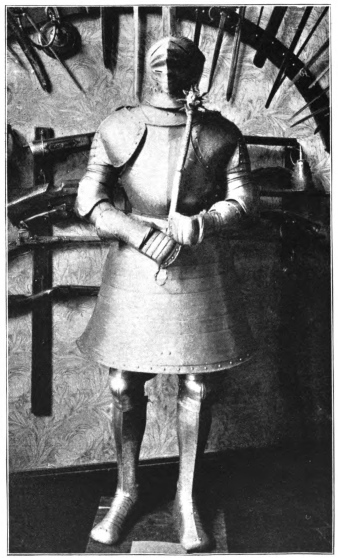

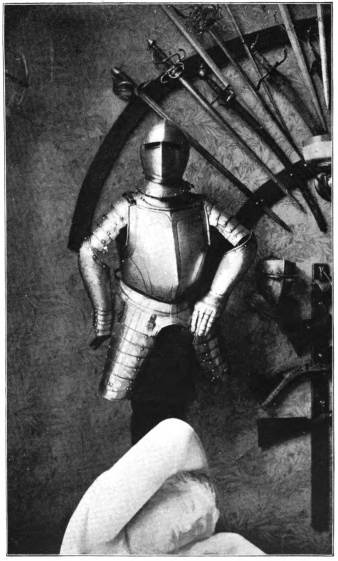

| 1. | TRANSITIONAL GOTHIC SUIT AT MUNICH | Frontispiece | |

| Face | |||

| 2. | GREAT HELMS AT BERLIN | 48 | |

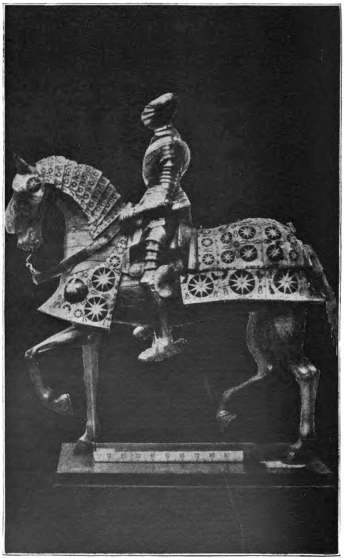

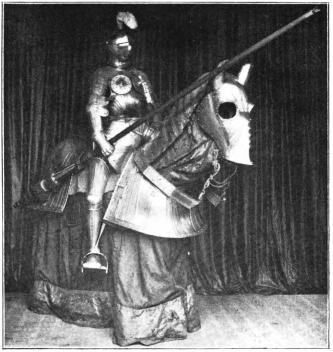

| 3. | MOUNTED SUIT WITH BARDS, IN THE KUNGL. LIFRUSTKAMMAR COLLECTION, STOCKHOLM | 67 | |

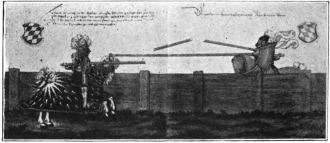

| 4. | SHARFRENNEN AT MINDEN IN 1545 | 88 | |

| 5. | SUIT AT DRESDEN FOR SHARFRENNEN, DATE 1554 | 88 | |

| 6. | TILTING SUIT AT NUREMBERG, FOR THE GERMAN GESTECH | 90 | |

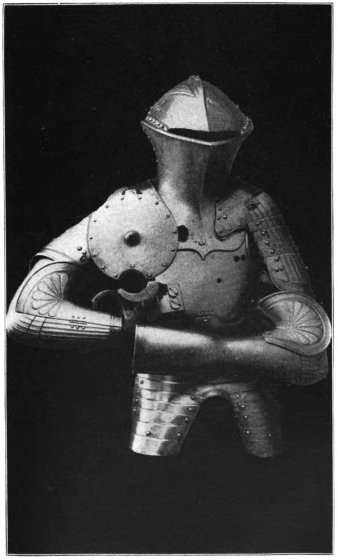

| 7. | TILTING SUIT FOR THE ITALIAN COURSE (WELSCHES GESTECH) | 91 | |

| 8. | AN ITALIAN COURSE AT AUGSBURG IN 1510 (WELSCHES GESTECH) | 91 | |

| 9. | ARMOUR FOR THE FREITURNIER AT DRESDEN | 92 | |

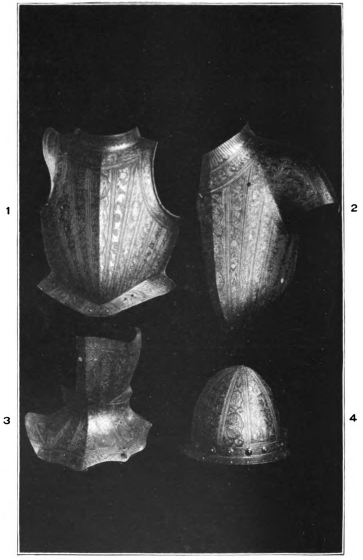

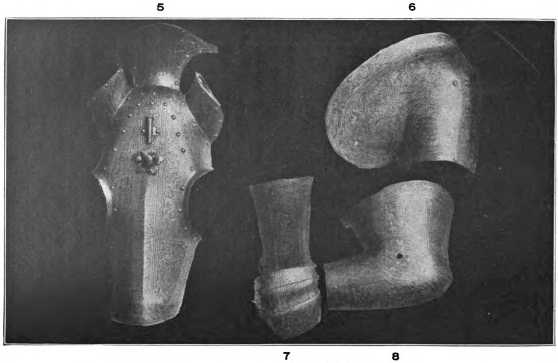

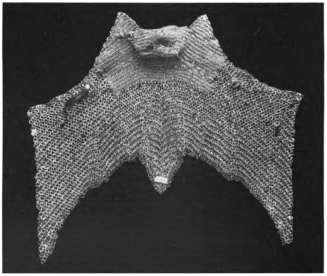

| 10. | REINFORCING PIECES FOR THE TOURNAMENT | 95 | |

| 11. | DO.DO.DO. | 95 | |

| 12. | TILTING HELM AT HAUGHTON CASTLE, NORTHUMBERLAND | 96 | |

| 13. | SALLADS, ETC. | 98 | |

| 14. | BRAYETTE IN CHAIN-MAIL, AT BERLIN | 109 | |

| 15. | PAGEANT SHIELD, FORMERLY IN THE COLLECTION OF PRINCE CARL OF PRUSSIA | 113 | |

| 16. | EFFIGY OF RICHARD BEAUCHAMP, EARL OF WARWICK, IN ST. MARY’S CHURCH, WARWICK | 119 | |

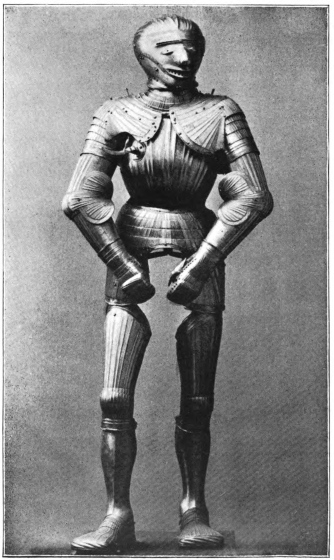

| 17. | GOTHIC SUIT AT SIGMARINGEN | 120xii | |

| 18. | GOTHIC SUIT AT BERLIN | 122 | |

| 19. | GOTHIC SUIT, IN THE AUTHOR’S COLLECTION | 124 | |

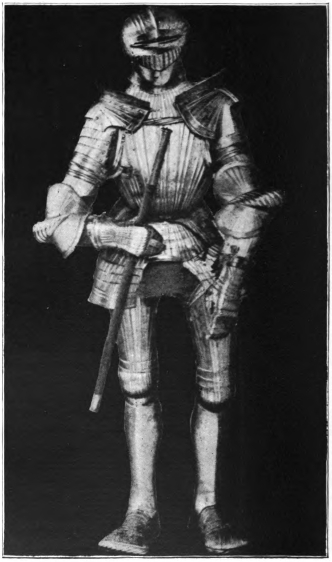

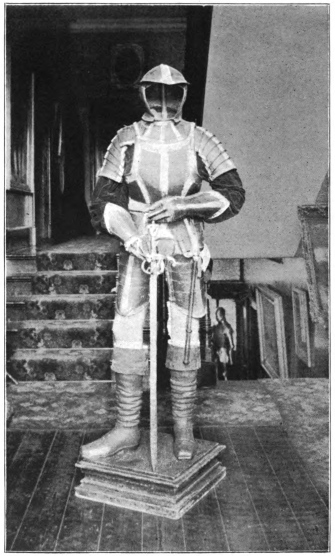

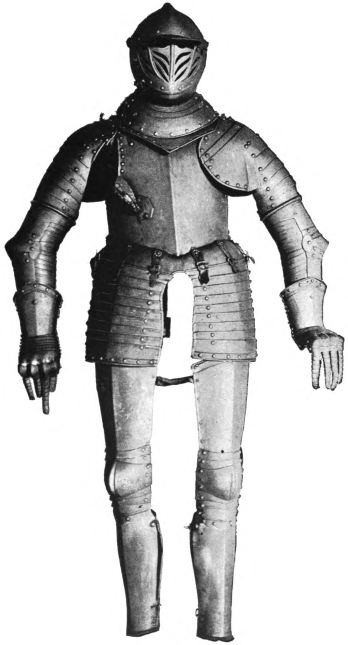

| 20. | FLUTED MAXIMILIAN SUIT AT BERLIN | 127 | |

| 21. | FLUTED MAXIMILIAN SUIT AT MUNICH | 128 | |

| 22. | FLUTED MAXIMILIAN SUIT, WITH GROTESQUE HELMET | 128 | |

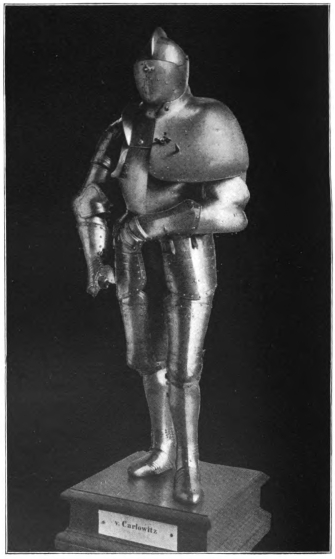

| 23. | PLAIN MAXIMILIAN SUIT, IN THE AUTHOR’S COLLECTION | 128 | |

| 24. | MOUNTED MAXIMILIAN SUIT, WITH BARDS | 130 | |

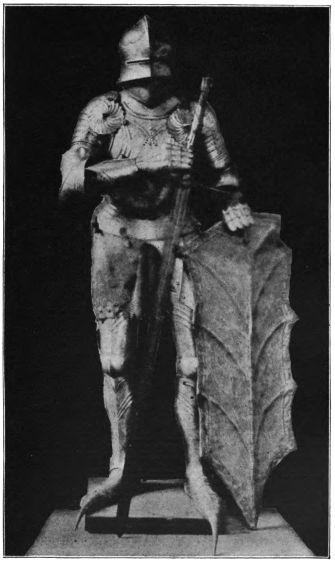

| 25. | SUIT WITH LAMBOYS, IN THE AUTHOR’S COLLECTION | 130 | |

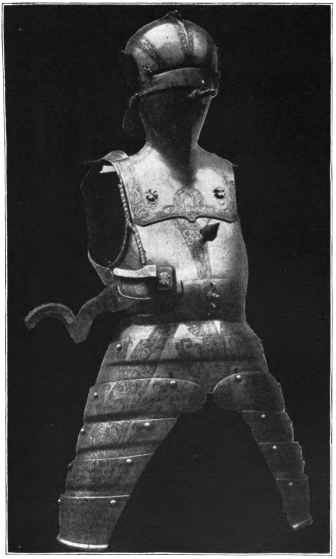

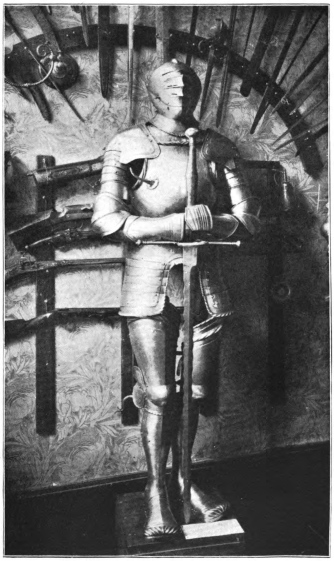

| 26. | SUIT BY PETER VON SPEYER OF ANNABERG, DATED 1560 | 135 | |

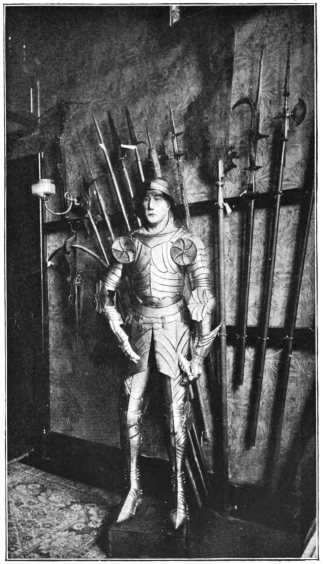

| 27. | PLAIN DEMI-SUIT, IN THE AUTHOR’S COLLECTION | 136 | |

| 28. | BLACK AND WHITE DEMI-SUIT, IN THE AUTHOR’S COLLECTION | 137 | |

| 29. | LATE SUIT AT MUNICH, 1590–1620 | 137 | |

| 30. | LATE SUIT AT BRANCEPETH CASTLE, DURHAM | 138 | |

| ENRICHED ARMOUR. | |||

| 31. | SUITS BY JÖRG SEUSENHOFER, OF INNSBRUCK | 141 | |

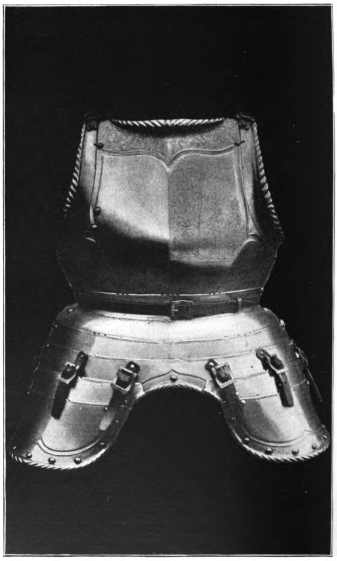

| 32. | CUIRASS AND TASSETS AT DRESDEN | 141 | |

| 33. | SUIT AT ALNWICK CASTLE, NORTHUMBERLAND | 142 | |

| 34. | SOME DETAILS OF THE SUIT AT ALNWICK CASTLE | 144 | |

| 35. | SUIT BY LUCIO PICCININO, OF MILAN | 144 | |

| 36. | REPOUSSÉ ARMOUR AT BERLIN | 145 | |

| 37. | SUIT OF THE DUC D’OSUNA | 146 | |

| 38. | SOME DETAILS OF THE OSUNA SUIT | 147 | |

| 39. | SUIT BY ANTON PEFFENHAUSER, AT MADRID | 148 | |

| WEAPONS.xiii | |||

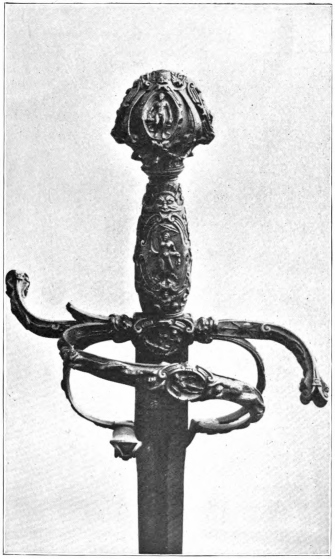

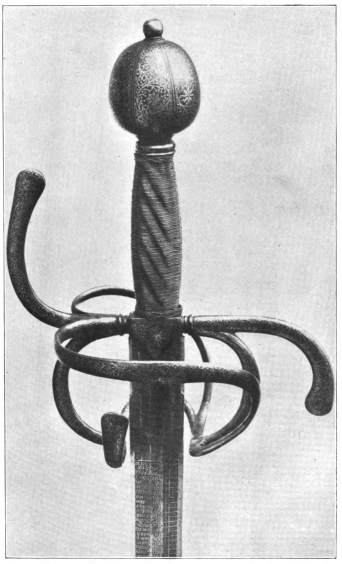

| 40. | ENRICHED SWORD, SECOND HALF SIXTEENTH CENTURY | 156 | |

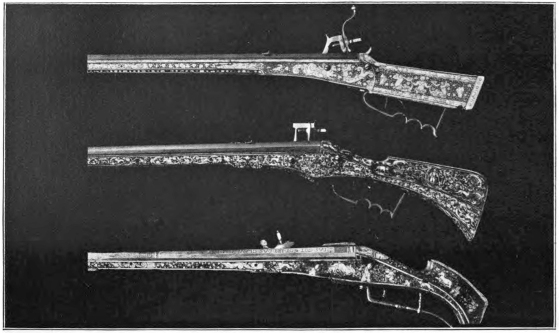

| 41. | HAND-GUNS, RENAISSANCE WORK | 157 | |

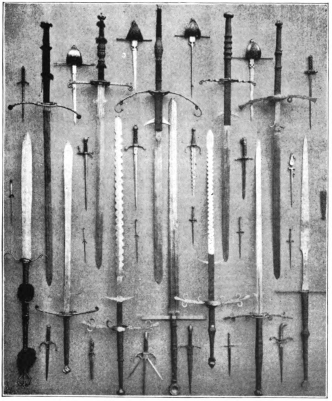

| 42. | TWO-HANDED SWORDS, FLAMBERGES, AND DAGGERS | 166 | |

| 43. | ANELACE AT BERLIN | 176 | |

| 44. | SWORD OF CHARLES V., ABOUT 1530 | 168 | |

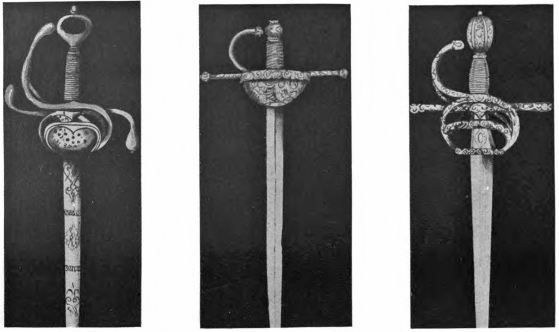

| 45. | RAPIERS—GERMAN, SPANISH, AND ITALIAN | 169 | |

| 46. | SCHIAVONA, IN THE AUTHOR’S COLLECTION | 173 | |

| 47. | CROSSBOWS AND QUARRELS | 185 | |

| 48. | PRINCIPLE OF THE BALLISTA | 204 | |

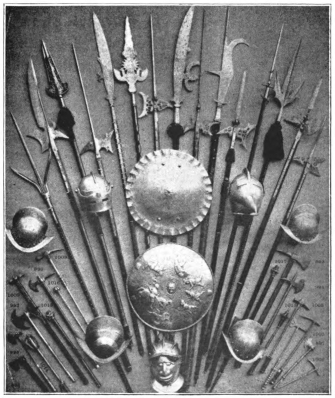

| 49. | STAFF AND CLUB WEAPONS, ETC. | 204 | |

| 50. | EARLY ARTILLERY | 210 | |

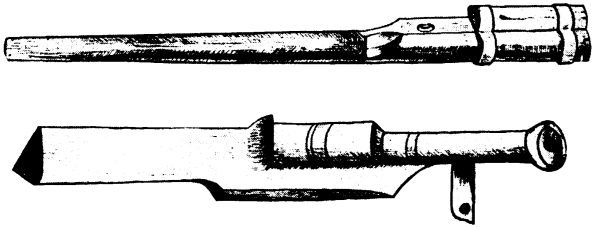

| 51. | EARLY HAND-GUNS | 228 | |

15

The phrases, “the Stone,” “Bronze,” and “Iron Ages” are mere generalizations fast losing their significance, and the purposes of this volume will not permit of any special disquisition on the weapons of these mixed and merging classifications of periods, or even those recorded of the Egyptian, Etruscan, Greek, Roman, and Eastern peoples; beyond what, in some instances, may seem necessary for showing any prototypes or analogies of arms or armour in use during the “Middle Ages” and the “Renaissance.”

The more remote ages of Egypt would have been a blank to us but for the character of the tombs, which preserved so wonderfully the papyri and frescoes we find so valuable, and, above all, the inscriptions and bas-reliefs on stone, affording infinite information concerning the arms of this ancient people and their16 martial achievements; indeed, we really know more of the weapons of the ancient Egyptians, and even those of the times of Hesiod, Homer, and Cambyses, than we do of those of the Goths, Vandals, Huns, and Ancient Britons during the centuries immediately following on the final evacuation of Britain by the Roman legions. The vigorous races that had been vanquished by imperial Rome, and those that in their turn had invaded and conquered Italy, inherited much from the earlier Roman wars and domination, more than has been thoroughly understood by historians of the nebulous centuries partly preceding and closely following on the final overthrow of the Western Empire; and the Romans had already gathered together many of the forms of the nations and empires that had preceded them, to say nothing of adaptations from the armament of contemporary tribes and peoples; still, in the main, the Romans had imposed their own methods and civilisation on all the nations they conquered. On a monument recently brought to light by M. de Morgan at Susa, erected by Naram-Sin about B.C. 3750, is a figure of the king wearing a horned helm, and armed with an arrow in his right hand and a bow in his left; a dagger is thrust into his girdle.

The granite sculptures of Persepolis show the weapons of the Assyrians to have been mainly those perpetuated for many ages and under many degrees of civilisation—viz., the sword, the lance or javelin, the sling and the bow; and in the rusty fragments of solidified iron rings in the British Museum, found at Nineveh, we see the ancestor of the Roman lorica, the bright byrnie of the “Sagas,” and hauberk of the “middle ages.” The same monumental inscriptions clearly indicate to which ancient people the Romans were indebted for their missile-casting engines, for here you have the catapulta and ballista, differing but little from those which were used by the Romans in the third century of our era, and doubtless handed down in17 their turn principally through the Franks to mediæval times. Strange it is that the principle involved, nay, the very machines themselves, have hibernated, so to speak, again and again!

An antique Greek drawing, representing Amazons fighting, in conjunction with Scythians, against Theseus at Attica, shows the following armament, viz.1:—Helmets of the Phrygian type; tunics coming half-way down the thighs, fortified with scales; and complete leg armour looking on the drawing like chain-mail, but probably, like the tunics, of small scale armour similar to that found at Æsica, referred to later in these pages. Two of the figures brandish long spears with leaf-formed heads, while the third is in the act of bending a bow, the arrow having a barbed head, and wears a quiver slung over the shoulder. They all have belts, and the tunics are ornamented with a geometrical border. Such long spears were also the weapons of the heavy Greek infantry. We owe, then, the inception of much of the arms and armour of European countries to the ancient civilisations of Asia and Egypt, and much also to the Etrurians, Greeks, and Romans; for, up to the middle of the fifth century, the countries as far as the Danube, in form at least, were still under the domination of Rome, so that Roman influence on armament must still have been very considerable; but with the final break-up of the empire of the West, at the end of the century, the old national and patriotic forms, which were of a more ponderous character, began to reassert themselves. These, again, became much modified, at a later period, in a considerable revival in the direction of Roman forms among the Franco-Germans, who aimed at a continuation or reconstruction of the traditional Western Empire. Another potent influence in the direction of change and interchange, concerning which we can merely speculate, was the18 swarming out of Eastern peoples, as well as the constant pressure from the frozen North towards the sunny South.

The analysis of the suits hereinafter presented will be prefaced by a short and concise sketch of mediæval and “renaissance” armour in general, and under its own section, that of the weapons of war, etc. This, no doubt, will be helpful in making the explanations clearer as regards nationality, fashion, and chronology.

During the earlier periods, and in fact throughout the entire time covering the use of defensive armour to its decadence, great difficulties constantly arise regarding the precise antiquity and nationality of specimens preserved, and, consequently, the fashions generally prevailing in a given country at a particular time. This uncertainty is greatly owing to immigration, invasions, and to the importation of foreign artificers, as well as of arms and armour from the more advanced countries to others less forward in mechanical skill, as applied to armour and weapon-making.

Some of the manuscripts, seals, effigies, brasses, and illuminated missals preserved, afford great help in deciding doubtful points; but very little of this kind of evidence goes farther back than the ninth century, besides being sometimes of a more or less fanciful and inaccurate character, and it is only by closely weighing and comparing that some reasonable degree of certainty can be got at.

In English brasses we have the best consecutive representation of armour, extending from that of Sir John Daubernoun, in the reign of Edward I., to that found at Great Chart, near Ashford, Kent, of the reign of Charles II.; but few have been preserved that date from earlier than the fourteenth century, though there are many military effigies. There was formerly a brass in St. Paul’s Church, Bedford, of Sir John Beauchamp (1208), and this would have been the oldest brass known19 had it been still to the fore. There is now an Elizabethan brass of a knight in this church. The figure on the brass of Sir John Daubernoun (1277), Stoke d’Abernon, near Leatherhead, Surrey, is entirely encased in mail, excepting, of course, the face. A large number of brasses may be seen in Boutell and Creeny, and you have the best series of effigies in Stothard and the continuation by Hollis. There are, besides, many other books treating both on brasses and effigies. The best German series exists in Hefner’s Trachten. Some of the foreign brasses are most artistic, but the iconoclast has left us only a couple of hundred, while the English brasses are to be numbered by thousands. The great majority of Continental brasses now left are in Germany and Belgium, while some half-dozen examples cover those of France, and there is only one in Spain. It must be borne in mind that the date on ancient monuments is that of death, so that the armour indicated may be the make of a quarter of a century earlier; besides, it may have been inherited by the defunct. There are also cases where these memorials were executed during the subject’s lifetime, or from contemporary models after his death. Suits were also sometimes “restored” by the armourer to correspond with a later fashion, and cases of this kind naturally give rise to some difficulty; and, as in the case of some Egyptian tombs, we have instances of misappropriation in English monuments. A case in point is the memorial of “Vicecomes et Escheator Comitatus Lincolniæ,” who died in the reign of Henry VIII. The armour is late fourteenth century, but to whom the monument was originally raised is unknown. Of course, the armour for the back is not shown on brasses and effigies. The Beauchamp effigy at Warwick affords, however, a notable exception, though this is of less importance owing to the fact of there being real armour of that period existing. Another valuable source of information arises20 from the custom prevailing during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, of leaving arms and armour as mortuaries to churches, and several helms and shields have come down to us in this way.

Later in these pages will be found a chapter headed “Details of Defensive Plate Armour.” This section deals as fully as a reasonable regard for space will allow with each important piece of armour, as regards its form, history, and chronology. It will serve also, to some extent, as a glossary of terms. It will be seen that there is usually a period of transition between the different well-marked styles of armour, just as is the case in architecture.

Remarkably little is known of Britain during the centuries immediately following the Roman occupation, and the question as to when real chain-mail was first used in Europe is both difficult and obscure. There is a representation of loricas on the column of Trajan that looks remarkably like chain-mail, and it is almost certain that the Romans used iron chain-mail in Britain. The bronze scales of a lorica, or Roman cuirass, found at Æsica, do not help us;2 but interlinked bronze rings of Roman origin have also been found, and if in bronze, why not in iron? This question is adequately answered by the masses of corroded iron rings of Roman times found at Chester-le-Street, and referred to in the report of a meeting held by the Newcastle-upon-Tyne Society of Antiquaries as far back as 1856.3 These rings could21 hardly be massed together as they are without having been interlinked. The extract from the report of this early meeting of the Society runs thus:—“The Rev. Walker Featherstonhaugh had presented two pieces of chain armour, corroded into lumps, from Chester-le-Street.” Similar masses of rings of Roman date have been found at South Shields, and may be seen in “The Blair Collection” at the Black Gate Museum. These are of a date certainly not later than the fourth century. We may then reasonably conclude that these masses of corroded iron rings were once loricas of iron chain-mail. But the Romans were not the first to use chain-mail, for they got it probably, like so much besides, from Asia. In the British Museum are some corroded masses of links brought from Nineveh, similar in character to those found at Chester-le-Street, so it may be taken that this kind of armour is of a remote antiquity.

The Dano-Anglo-Saxon epic poem of “Beowulf,” written doubtless during the second half of the eighth century, bears frequent reference to the hero’s arms and armour:—

| Beowulf maœlode, | Beowulf spoke (or sang?), |

| On him byrne scan, | He bore his polished byrnie, |

| Searonet seowed | The war-net sewn |

| smipes orpanum. | by the skill of the smith. |

This poem has been cited as proof that chain-mail was in use in early Saxon England, and by the Vikings also, and there is some supposed confirmation of this idea as regards the latter in the finds of chain armour in the peat mosses of Denmark, which have been freely ascribed to the fifth and sixth centuries; but this mail is of such excellent workmanship, and so similar to that made at a much later period, as to cast grave doubts on this deduction, and there is really nothing whatever to show that it was of so early a date. Every ring of the Danish mail is interlinked with four surrounding rings,22 and so on throughout the garment. This is the prevailing fashion of all periods, and there is a great variety of mesh. It would seem that the “war-nets” alluded to in “Beowulf” were not chain-mail at all, but leathern or quilted armour with pieces of iron, shaped like the drawn meshes of a net, or steel rings sewn on to it, and that this combination constituted the “bright byrnie”4 referred to in the poem, and that the chain-mail found at Vemose, Flensburg, and other places, was made much later. Quite independent of other evidence, the line in the poem, “The war-net sewn by the skill of the smith,” would point to the leathern or quilted tunic being fortified with rings or scales sewn on to the garment; and this was the general method up to and even beyond the time of William the Conqueror.

There are, however, other words in the poem referred to, such as “hand-locen” (hand-locked), and “handum gebroden.” The latter words might well read either twisted or embroidered with hands, while both might point to interlinked mail, so it clearly cannot be affirmed with certainty that there were no instances of real chain-mail in use in Britain at this very early period after the Romans; but if there were any hauberks of the kind it might indicate a much greater continuity from the Roman occupation than the historians of those shadowy times have hitherto imagined. Possibly chain-mail was introduced from Asia, through the Vikings, and that the byrnies mentioned in Beowulf were really made of interlinked rings; but it is probable that there was no real chain-mail in Northern Europe between Roman times and the ninth or tenth century. That it was in use in the East at an early period is shown by the discovery of a chain-mail tunic in a “barrow” in the Ukraine.5

The Arab hordes which were driven back by Charles23 Martel at the decisive battle of Poitiers in 732 were despoiled of their body-armour, which was of a rich Saracenic character, by the conquerors. This was probably of leather or quilted stuff fortified with small plates or scales; and such armour was henceforth adopted by the Franks, while Charlemagne grafted Roman fashions and traditions on to the armament.

Up to the later middle ages the sizes of the links of chain-mail, which are of hammered iron, vary considerably, extending from one-sixth of an inch to an inch in diameter, and they were soldered, welded, or butted in the earlier times, and often riveted in the later. Most of the earlier Oriental mail is riveted. It is said that the art of wire drawing was discovered by Rudolph of Nuremberg in 1306. At all events its application at this time rendered chain-mail much cheaper and more generally used than when each ring was separately wrought. This discovery was possibly only the revival of an ancient art. Very much was lost during the “dark ages” which followed the disruption of the Roman empire, when so many landmarks were swept away; and the same kind of thing has happened often before in the cycles of obscuration that preceded it. Much was preserved in “Chronicles,” as was also the case in the earlier periods of obliteration, when hieratic writings on stone, papyrus, or parchment restored so much to the newly-awakening times. Double-ringed mail is mentioned by some authorities, but the author has never seen any, and it seems probable that the indistinct drawings on manuscripts, brasses, or tapestry gave rise to the idea—very small ringed mail might easily be taken for double; still, many effigies show what looks very like double-ringed mail.6 The Danes of the eighth century generally adopted the Phrygian tunic, reinforced with steel rings, probably obtained through their intercourse with the24 Byzantine empire; and both Meyrick and Strutt agree that such a tunic was then in use. The paladins of Charlemagne wore jazerant and scale armour of strongly marked Roman characteristics, and, according to the monk of St. Gall, the emperor’s panoply consisted of an iron helmet and breastplate of classic form, with leg and arm armour. This period represents to a certain extent a classic revival, and such forms were clearly then reverted to. It was under this reign that heavy cavalry attained the pre-eminence which sustained its first check with the successes of the English yeoman with the longbow. Charlemagne adopted the service of the ban, and formed a standing militia of his own vassals.

The real mediæval coat of chain-mail was probably somewhat of a rarity in the tenth century, but that it was in general use by the greater knights late in the eleventh is clear from the testimony of the Princess Anna Comnena, daughter of the Emperor Alexius Comnenus, who says, in describing the body armour of the knights of the first crusade, “it was made entirely of steel rings riveted together.” She further remarks that this kind of armour was unknown at Byzantium up to the time of the first crusade. Mail armour is mentioned by a monk of Mairemoustier (temp. Louis VII., a contemporary of Stephen, 1137), in a description of the armament of Geoffrey of Normandy.7

The inception and principles of chivalry were the romantic outcome of the lessons of Christianity as taught in the earlier “middle ages,” though confined to a narrow and privileged class; which class assumed a concrete form under Charlemagne, who did his best to divide society into “the noble” and “the base”; thus promoting the feudal system, the symbol of which became the sword. The earlier stages of the movement were characterised by great fervour and self-abnegation, operating in various ways according to the modes of25 thought of the different nations brought under its domination. It gradually declined, and by the end of the thirteenth century had degenerated into a fantastic fashion rather than a principle; and culminated, like the church of the period, in licentiousness and frivolity. Froissart alludes to it in this sense. The influence exercised by the laws of chivalry was on the whole beneficent in subjugating the rude passion of combat to some of the limitations of Christian ethics; and the knightly watchword “God and his lady” raised the social status of women of the privileged class. The conquest of England by the Normans, the stirring incidents of the first crusade, when we have the shrewd account of the arms and armour of the crusaders by the Byzantine Princess Anna Comnena, and the general martial spirit of the age, lent an immense impetus in the eleventh and twelfth centuries to warlike equipment of all kinds; but this was more in the direction of improving old forms, rather than in the introduction of new ones.

The Bayeux tapestry—worked, there is little doubt, in the middle of the eleventh century, but whether embroidered in England by order of Matilda for an English cathedral, or in Normandy by noble ladies or hirelings—is of comparatively little moment so long as its authenticity as an approximately contemporaneous monument of the reign of the Conqueror is generally admitted, and this is happily the case. It shows that the Conqueror’s chivalry wore conical helms with the nose-guard and hood of mail for protecting the neck, shoulders, and part of the face. The hauberks reached down over the thighs, with a slit in the middle of the skirt for convenience on horseback; and the mail on the arms usually came nearly to the elbows, but sometimes to the wrists; and the continuous coif occurs frequently. The hauberk of this period had no division down the front, but was drawn on over the warrior’s head. The Norman knights bear pear-shaped, convex shields with a point at the26 bottom, secured to the arm by a leathern strap, and large enough to cover the body from the shoulders to the hips; some with a rough device. Some of the shields shown are polygonally formed, with a central spike. The Saxon shields on the tapestry are round or oval, with a central umbo. Maces are shown in the hands of some of the figures. With the exception of William himself, whose legs are encased in chausses, probably of leather, with reinforcing scales or rings, the limbs of his knights are simply swathed in thongs. Probably only the richer knights wore chain-mail, the majority having hauberks of cuir-bouilli (boiled leather) strengthened by continuous rings sewn on to it, side by side or overlapping. Some also had the pieces of lozenge-shaped metal already mentioned, called jazerine or jazerant; or scales, which were occasionally of horn, fixed on to the leather. It is impossible to determine these details absolutely, as all the armour looks very much alike on the tapestry in its present condition, this being especially the case where rings were used; and it is only by careful comparison with other contemporary evidence that any reasonable certainty can be assured. This has naturally given rise to a great diversity of interpretation; and the same difficulty arises with seals. The knights wore no surcoats over their mail. The great seal of William the Conqueror shows him in a hauberk coming down to the knees, with short sleeves and no leg armour. Under the hauberk was the gambeson and tunic. The helm is hemispherical, and fastened under the chin. The Germans were probably before us in the general use of real chain-mail, for the epic poem of Gudrun, written in the tenth century, states how Herwig’s clothes “were stained with the rust of his hauberk.”

The panoply of knights was very much the same during the century preceding the Conqueror’s time, as shown in the illuminations of a “Biblia Sacra” of the tenth century. Helms with rounded crowns27 were worn then, and this is all confirmed by the “Martyrologium,” a MS. of the same period in the library at Stuttgart.

Defensive armour continued much the same during the reign of Rufus, whose seal shows him in a long-armed hauberk without gloves of mail, and a low conical helm with the nasal; but in the reign of his successor, Henry I. (1100–1135), the reinforcing rings of the hauberk were sometimes oval and set on edgeways, “rustred” mail as it was termed; and this fashion became common in the next reign. The seal of Henry I. shows a conical cap without nasal, and that of Stephen a kite-shaped shield with a sharp spike in the centre. The king wears a hauberk of scales, sewn or riveted on the gambeson. The nasal first appeared in England about the end of the tenth century, and the Bayeux tapestry shows it to have been common among the Normans in the eleventh. Among the seals of the English kings, that of Henry II. is the first to show the hood of mail. The hauberk of the Norman kings was in one piece from the neck. Under Richard I. the hauberk is somewhat lengthened, and armorial bearings become general. The sleeves of the hauberk are lengthened, and terminate in gloves of mail. The first seal of Richard Cœur-de-Lion shows the king on horseback in a hauberk of mail. His spiked shield, shaped like half a pear cut lengthwise and pointed at the bottom, is ensigned with a lion rampant. The arm is mail-clad to the finger tips, and brandishes a simple cross-handled sword; the chausses are of mail, and terminate in a spurred solleret. Over the continuous hood, which is in one piece with the hauberk, he carries a high conical helm without flaps or nasal, bound round with iron bars. On Richard’s second seal he bears the great helm with a fan crest, ensigned with a lion; his hauberk is rather longer than in the first seal. The shield on this seal is ensigned with three lions passant gardant, and this is28 still retained on the royal escutcheon of England, which becomes quartered with the lilies of France in the royal arms of Edward III. Both seals show the plain goad spur. There is a good example of an undoubted suit of chain-mail on an effigy of Robert de Vere (died 1221) in Hatfield Broad Oak Church. This suit was probably made in the reign of King John. An effigy in Haseley Church, Oxfordshire, of the reign of Henry III., shows a hood somewhat flattened at the crown, hauberk reaching to the knees, and surcoat coming nearly to the ankles.

It is stated that Richard sent home from the crusade numerous suits or rather hauberks of chain-mail. There is a riveted sleeveless shirt of chain-mail, with a fringe of brass rings, dating from the thirteenth century, in the Rotunda, Woolwich; these brass rings are a common feature of the period.

The question as to when coats of arms were first introduced is very uncertain, but it is thought that the custom had its origin in the first crusade, when distinguishing marks among such a motley crowd of warriors were more especially needful. During this crusade the several nationalities taking part in it were distinguished by different coloured crosses sewn on to their garments, each leader displaying his own colour and device; but heraldic bearings first became generally hereditary in the reign of Henry III. His seal shows the king with the fingers of his chain-mail gloves articulated, and wearing the great helm. An early example of a helm with a heraldic device occurs on an effigy of Johan le Botiler about 1300. It is figured in Hewitt. The shield on the brass of Sir John Daubernoun bears a distinctly heraldic device. Heraldry seems to have been most studied, prized, and practised during the fourteenth century. An illumination in the Loutterell Psalter, dating from the middle of the same century, shows heraldic devices spread over the entire person of a knight; being29 emblazoned over the body, ailette, banner, pennon, saddle, shield, and on the housings of the steed, as well as on the dresses of the ladies of the knight’s family. The numerous tournaments of this period encouraged its use and development, mainly in the sense of ostentation and pride of birth. In the Tower collection is a figure on horseback clad entirely in chain-mail. To the hood is attached a fillet of iron round the head. The hauberk has long arms terminating in gloves of mail. A leathern belt with strong iron clasps encircles the waist. Excepting the legs the horse is fully barded with leathern armour, fortified with iron scales. The armour on the figure is labelled “Indian,” and the horse “Persian.” There are two hauberks at Carlsruhe of riveted chain-mail, hood and tunic in one piece, but the head bears no fillet. On the breast, over nipples and navel, are three small palettes inscribed with Oriental characters; and inscribed clasps at the waist fasten the tunic. These suits are chiefly remarkable for the presence of the hood, and the date of the mail is about fourteenth century. There are two shirts of mail at Brancepeth Castle, Durham, which are riveted, and probably of early fourteenth century date. It was not uncommon for hauberks to be provided with reinforcements of leathern thongs, which were intertwined through the rings; there is an example of this kind in the Rotunda at Woolwich. This description of reinforced chain-mail is referred to later under the paragraph dealing with “banded” mail. An effigy of a knight in the Temple Church, that of Geoffrey de Mandeville, Earl of Essex (1144), in the reign of King Stephen, engraved by Stothard, shows the warrior armed completely in chain-mail, having a hood of mail over the head and shoulders, surmounted by a cylindrical helmet without nasal. The hauberk is in one piece with the arms and gloves, the last without any articulation; this form of gauntlet is the earliest. Chausses going above the knee, in one web with the30 demi-poulaine or slightly-pointed shoes; globular triangular shield extending from the shoulder to the hip; and the belt of knighthood above the hips. There is a singular point in connection with this and two other effigies in the church, viz., that the sword is worn on the right side. This peculiarity is noticeable in other figures of the period. The effigy of a knight in the same church, that of William Longespee, Earl of Salisbury (1200–1227), wears mail gloves, the fingers of which are articulated; the sword is on the left side. Both figures wear surcoats. Like most continuous hoods of early thirteenth century date, this example is somewhat flattened at the top. They were usually rounded in the second half of the century, as shown on the Daubernoun brass; and the gloves generally divided into fingers, as may be seen on two of the sleeping guards in Lincoln Cathedral; this form continued well into the fourteenth century; The “Coif de mailles,” or separate hood of chain-mail, followed the same lines as the continuous one, and examples of all may be seen in Stothard’s series, and one of the effigies in the Temple Church shows how they were lapped round the face and fastened. What the separate hood perhaps gained in convenience, it certainly lost in invulnerability, as it left the neck less adequately guarded against a thrust from below. The effigies in the Temple Church are perhaps the most artistic, as well as the most interesting, of any series existing. It is not known that any of them really represented a knight templar, although several of them did crusaders. The only effigy of a knight templar that is known to have existed is that of Jean de Dreux, who was living in 1275. The figure was unarmed, but bore the mantle of the order. The effigy was formerly in the church of St. Yved de Braine, near Soissons.

A knight in Walkerne Church, Hertfordshire, wears the great helm, rising slightly at the crest, pierced with eye-slits, and showing breathing holes over the mouth.

31 Coutes or coudières for the elbow are seen but rarely in the thirteenth century; but genouillières (knee pieces) began to appear over mail towards the middle of the century. Examples of both pieces, dating about 1250, may be seen in Stothard. Genouillières occur on the Daubernoun brass (1277), while both pieces appear on that of Sir John D’Argentine (1382). The adoption of these defences and the plastron-de-fer was the first step in the direction of plate armour. Something of the kind had become absolutely necessary by reason of the number of casualties caused by the general use of the deadly battle-axe and mace.

The cuisse and jamb (plate armour for the thigh and shin) are not seen in England before the close of the century. They were first strapped on over the chausses, and only covered the front of the leg. Chain-mail continued in use in the East up to a recent date.

A spirited drawing of a mediæval water ewer of bronze is given in the Archæologia Æliana, old series, vol. iv., p. 76, Plate XXII. This ewer, which was found about four miles west of Hexham, represents a knight of the thirteenth century on horseback, wearing chain-mail, and over it a sleeveless chequered surcoat. The figure wears a flat-topped cylindrical helm.

The epoch of chain-mail armour, pure and simple, may be said to close during the reign of Edward I., although in more remote and less advanced countries, such as Ireland and Scandinavia, it was to be met with very much later. There was a revival in the use of scale armour in the fourteenth century, and there are many instances. It was usually applied in pieces such as chaussons, chausses, gauntlets, or sollerets. It is often met with on German monuments. An English example occurs on the brass of Thomas Cheyne, Esquire (1368), at Drayton Beauchamp, Bucks. The mailed horseman continued the main force in every army in the field up to the reign of Edward III.

32 A good idea of the equipment prevailing towards the close of the century is shown in the will of Odo de Rossilion, dated 1298: he bequeaths “my visored helmet, my bascinet, my pourpoint of cendal silk, my godbert (hauberk), my gorget, my gaudichet (mail shirt), my steel greaves, my thigh-coverings and chausses, my great coutel, and my little sword.”

The surcoat was a device for protecting the armour against wet, and to mitigate the rays of the sun. It is rare towards the close of the twelfth century, when you have an instance in King Sverrer, who wore a rose-coloured surcote (“raudan hiup”). The garment becomes common in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, when the ground of the fabric was usually green. There are both sleeveless and sleeved varieties, but the latter did not come into vogue before the second half of the thirteenth century. There is a north-country example referred to in Surtees’s History of Durham (vol. iii., p. 155); one on the effigy of an unknown knight in Norton Church; and another in the Temple Church, London. Among the seals of the kings of England this garment first appears on that of John. Chaucer, writing in the reign of Edward III., says:—

The “cote-armoure of Sir Thopas” is the surcoat. There is an admirable example of a thirteenth century surcoat on the figure on the ewer found at Hexham, which has already been referred to. This surcoat is long and sleeveless, with a slit in front. It is embellished by a diamond pattern, interspersed with fleurs-de-lis and stars of six rays. The garment has an ornamental border. A representative example may be seen on the Daubernoun brass. It reaches below the knee, is slit half-way up the front, and is fastened by a cord at the waist. The border is fringed. The surcoat early in the33 fourteenth century was long, but became gradually shortened and tightened. There are, however, earlier examples of the shorter surcoat, as shown on the Whitworth effigy, which does not reach the knee. The D’Argentine brass (1382) furnishes a good example of the short fourteenth century surcoat, and another may be seen on the effigy of the Black Prince (1376) in Canterbury Cathedral. It is a sleeveless garment reaching a little below the hips, and was variously fastened, being buttoned, laced, or buckled. On an effigy engraved by Hollis in his Plate II., it is held together by a brooch. The fabrics were rich and costly, and usually ornamented with heraldic devices. The surcoat on the figure of the Black Prince is charged with England and France quarterly, with a label of three points. At this period but little of the trunk armour showed through the “cyclas.” The helm on the figure of the Black Prince was gilt or silvered, and had its scarlet mantling. The surcoat of the fifteenth century presents heraldic devices on the front and arms, both before and behind, indeed it was a “tabard of arms,” and so it continued in the sixteenth century as a herald’s tabard. The garment, of course, gave rise to the term “the coat of arms.” An effigy of Sir John Pechey, figured by Stothard, shows a tabard of arms over the armour; and so does the brass of Sir John Say (1473) at Broxbourne, in Hertfordshire. The short surcoat had almost ceased with the second quarter of the century, although there are still isolated examples, such as the short-sleeved tabard on the Ogle effigy at Bothal, Northumberland, which is early sixteenth century. During the first half of the fourteenth century, English knights wore a garment under the surcoat, called “upper pourpoint”; the true “pourpoint” was the surcoat itself.

A description of the “Ehrenpforte,” written in 1559, gives a representation of the meeting between Henry VIII. and the Emperor Maximilian, which occurred in34 1519. The emperor wears a surcoat with slashed sleeves and plaited skirt, obviously suggested by the civil dress of the period, called “bases.” The knightly mantle is but rarely seen on monuments. It was one of the insignia of the Garter, and was usually blue in colour. There is an instance figured by Stothard, Plate LVIII. There were two grades of knights instituted—the banneret and the bachelor. The former had his square banner as well as pennon, and square shield for armorial bearings; his retinue consisted of fifty men-at-arms and their followers. The knight-banneret, so called from having the right to bear a banner, was always a man of large estate, with a great number of retainers. Knight-bannerets first appear during the reign of Philip Augustus, and disappear by ordinance in the reign of Charles VII. The Gloss du Droit, Fr. de Laurica defines the etymology of the term “bachelor” as here applied. It does not signify “bas chevalier,” as has often been supposed, but refers to the minimum extent of land that a candidate for the honour must be possessed of, viz., four “bachelle” of land. The “bachelle” contained ten “max” or “meix” (farms or domains); each of which contained a sufficiency of land for the work of two oxen, during a whole year. It would thus appear that the dignity of knighthood was only conferred on men possessing a suitable estate, and that the two grades were based on the extent of estate; which, of course, implied the number of vassals available for military service. Although the pennon was the ensign of a knight-bachelor, we have the authority of Du Fresne that an esquire could also bear one, always providing that he could ride with a sufficient number of vassals.

Orders of knighthood appear to have originated in France, and were introduced into England probably by the Normans. The most ancient order was the “Gennet,” instituted in 706. It was a military order, but always partook, more or less, of a religious character. The aspirant35 was usually trained to arms as a page, then he became an esquire, in attendance on a knight. It was unusual to confer the dignity of knighthood before the age of twenty-one had been reached. Knighthood was conferred by the “Accolade,” which appears to have been originally an embrace, but later consisted in the administering of a blow on the neck by the flat of a sword. There was an intermediate grade between a knight and an esquire in the pursuivant-at-arms, but the dignity of knighthood was very often conferred on a simple esquire.

Mamillières were circular plates over the paps, with rings affixed. Chains passed through the rings, one being usually attached to the sword and scabbard. These pieces were introduced in the reign of Edward I., and prevailed during the fourteenth century, more especially in the first half. Instances are comparatively rare. There is a beautiful example on an effigy of Otto von Piengenau (1371) in the church at Ebersberg. The chains are attached over the right breast, one fastened to the sword and the other to the dagger. Another on the tomb of Alb. v. Hohenlohe, died 1318. An instance of a mamillière over the left pap, with a thin chain attached to the helmet, occurs on an effigy of Berengar v. Berlichingen, 1377. On an effigy of Conrad von Seinsheim (1369), on his tomb at Schweinfurt, chains connect dagger, sword, and helm. The wood carving in Bamberg Cathedral (1370) affords two remarkable cases, where they directly appear on the almost heart-shaped “plastron-de-fer.”8 An English example may be seen on the figure of a knight in St. Peter’s Church, Sandwich. This interesting effigy is also remarkable for skirts of scale-work. The scales are ridged, and are probably of iron. They form the skirt of a garment which is worn between the hauberk of chain-mail and the surcoat. The effigy would appear to date from very early in the fourteenth century. Scale-work frequently36 occurs on monuments of this century, seldom covering the whole body, but more generally defending the hands and feet. Mamillières are present on an effigy in Tewkesbury Abbey Church, the date of which is doubtless about the middle of the century. A beautiful instance may be seen on an effigy at Alvechurch, Worcestershire (1346), showing clearly the one chain connected with the scabbard and another with the hilt. There is a brass in Minster Church, Isle of Sheppey, which represents an armed figure with only one “mamillière”; it is on the left pap, with the chain going up over the left shoulder—early fourteenth century. The derivation of the word is interesting, being from mamilla, the breast. Its origin was a leather band worn by the Roman ladies to support the breasts.

In effigies the knight’s head is usually pillowed on a helm, while a dog or lion crouches at his feet; this latter feature is supposed to be emblematic of fidelity.

There are frequent representations on monuments and in MSS. of a kind of armour that appeared towards the end of the thirteenth century, “banded mail” as it is called; but there has not been any general determination arrived at as to what it really was, and there are no actual specimens for reference. It presents somewhat the appearance of the “rustred” mail of the middle of the twelfth century—that is, of rings set on to the hauberk edgeways. On monuments and drawings these rings frequently appear to be set in continuous rows, whereon the rings turn in a right or left direction alternately; each line of rings being “banded,” or framed with what looks like a rim. Examples of this mail may be seen in Stothard’s series.9

37 We reach the highest point of mediæval culture during the fourteenth century, and broadly the “renaissance” towards its close. Like all periods of transition, it presents many points of interest, especially in armament. It was not before the middle of the century was reached that arms and armour approached to anything like uniformity. In the first moiety the greatest possible irregularity prevailed. Scale armour was still largely used throughout the century, and splint armour also, though to a less extent. An example of the latter may be seen on the effigy in Ash Church.

A combination of mail and plate armour, the latter strapped on, was in general use in England late in the reign of Edward the Second, when the helm, cuirass, or rather breastplate, and gauntlets were all of plate, and sometimes the cuisse and jamb; but the leg armour was often of cuir-bouilli. Chaucer says; “His jambeux were of cure-buly.” An inventory, dated 1313, of the armour which belonged to Piers Gaveston, includes breast and back plates, and two pairs of “jambers of iron”; but most of the monumental figures are still clad in chain-mail and genouillières. These “jambers” were only front plates for strapping on. An effigy of Sir William de Ryther, who died in 1308, shows genouillières of plate on a suit of chain-mail, with the hood covered by a bassinet. This was probably thirteenth century armour, although somewhat early for an example of the bassinet. The earliest brass we have, that of Sir John Daubernoun (1277), exhibits genouillières in a most artistic form. An effigy in Bedale Church, Yorkshire, that of Brian Lord Fitz Alan, wears38 genouillières over chain-mail, like the Daubernoun brass. He died 1302. Mixed armour continued longer in use in England and Belgium than in Germany, which latter country and Italy always led the way in defensive armour.

An effigy in Hereford Cathedral Church of Humphrey de Bohun, Earl of Hereford and Constable of England (died 1321), engraved by Hollis, wears the camail, a tippet of mail laced to the bassinet, which falls like a curtain over the shoulders, hauberk of mail to the knees, rerebrace, vambrace and gauntlets of plate, the fingers covered with laminated plates, genouillières, jambs with hinges and very slightly pointed sollerets, all of steel, with rondelles to protect the inside of the elbow. Here we have a good example of the transition to full plate armour, as attaching plates are replaced by rounded ones, fitting round the limbs, but still strapped on. An inventory of the earl’s effects (1322) appears in the Archæological Journal, vol. ii., p. 349. The bassinet is mentioned as being covered with leather. Other good examples of the lacing of the camail occur on the D’Argentine brass, and on an effigy of a knight of the De Sulney family in Newton Solney Church, Derbyshire. A figure standing in the nave of Hereford Cathedral, that of Sir Richard Pembridge, K.G., who died a year before the Black Prince, wears mixed armour—camail and bassinet with the great helm.

Both the goad and rowel spurs were in use throughout the fourteenth century. The figure of the Black Prince (1376) in Canterbury Cathedral is clad almost entirely in plate, and shows the prince wearing a conical bassinet with camail attached. Breastplate, épaulières, rerebrace, vambrace, coudières, leg armour, and gauntlets, all of plate—his great crested helm has a mantling, or lambrequin, and cap of maintenance, and is surmounted by a gilded leopard; besides the ocularium, it has a number of perforations on the right side in39 front, in the form of a crown, for giving air. There are gads (knobs) on the knuckles for the mêlée, which take the form of small leopards, with the usual spikes on alternate first joints of the fingers. The surcoat is quilted to a thickness of three-quarters of an inch; and this precious relic is the only actual garment of the kind that has come down to us. The material is buckram faced with velvet—lions and fleurs-de-lis embroidered in gold thread. This surcoat is short, and laced at the back. The brass of Sir John D’Argentine, Horseheath, Cambridgeshire (1382), shows a bassinet with camail. The brassards are complete, with articulated shoulder-plates, and gauntlets with finger articulations. The chaussons are of studded mail, and jambs, genouillières, and sollerets of steel, while a short surcoat covers the trunk, and the spurs are of the rowel type. Shields disappear from brasses and effigies in this century, the last example on a brass occurs in 1360.10

A brass in Wotton-under-Edge Church, Gloucestershire, shows a figure in mixed armour of Thomas Lord Berkeley, who died in 1417. The sollerets are “à la poulaine,” though not in the extreme form, and the gauntlets have articulated fingers and a sharp gad over each knuckle. The figure wears a collar of mermaids, the family cognizance. We now get very near to full-plate armour on an effigy of Sir Robert Harcourt, K.G., in Stanton Harcourt Church, Oxfordshire. The figure wears a horizontally fluted bassinet; a standard of mail; coudières sharply pointed at the elbow; cuirass with lance-rest; laminated taces, and long triangular tuilles; sollerets slightly laminated and pointed. There is a great crested helm with the figure. Sir Robert died in 1471, and the armour was probably made in the first half of the fifteenth century. This is a late example of the use of the standard of mail, but it40 probably covered a defence of plate, as was often the case. The steel gorget came in with the House of Lancaster. Several of these effigies and brasses have been engraved by Hollis.

It may profitably be mentioned again here that dates on monuments are those of demise. The armour, therefore, may be much earlier, sometimes a generation or so before the date of death; and it was common, nay, usual, for a knight to bequeath his suit or suits to his sons or other persons. For instance, Guy de Beauchamp, who died in 1316, bequeathed to his eldest son his best coat of mail, helmet, etc.; and to his son John, his second suit. It is obvious, however, that many effigies represent the fashion of armour prevailing at the date of demise, or even later. Mixed armour in France went well into the fifteenth century. Broadly speaking, mixed armour was used in England during the last quarter of the thirteenth to the end of the fourteenth century, but nearly full-plate armour began to be seen there in the reign of Richard II. It had, however, been in vogue in Germany and Italy for some decades before it was generally worn by the English, and it is probable that the earlier complete suits in England were imported from Germany or Italy, which countries set the fashion. Studded armour was not uncommon during the second half of the fourteenth century, and even earlier. The effigy of Gunther von Schwarzburg, King of the Romans (1349), shows the body armour to have been of mail, with reinforcing plates for the arms and legs, on which blank and studded lengths are interspersed. He wears the bassinet with camail. The following examples will show to some extent the progress of the evolution in Belgium. A figure in the library at Ghent, of Willem Wenemaer, wears genouillières and jambs of plate, otherwise clad in mail (1325). The sword is covered with a Latin inscription. A brass at Porte de Hal, Brussels, shows John and Gerard de Herre (1398) in41 mixed armour. On a brass in the Cathedral at Bruges, dated 1452, Martin de Visch has a full armament of plate, excepting the gorget, which is covered by a standard of mail.

This continuous strengthening of armour was clearly rendered necessary by the ever-increasing power and temper of weapons of attack, which was met by a corresponding effort at defence on the part of the armour-smith. We have the same sort of thing to-day in the constant competition between armour-plates and heavy guns. Then, again, weapons were invented to attack some vif de l’harnois, or vulnerable place, which was parried in its turn by an alteration or addition in the harness to resist it. The mortality in these days in battle was chiefly on the defeated side, and it took place mostly among the unhorsed combatants.

The crusades exercised a cosmopolitan influence over both arms and armour in Europe, not only in the introduction of new forms from the East, but also in a general assimilation of fashion among the nations of chivalry. The military administration of these two centuries of disastrous warfare, in and towards Palestine, was simply deplorable; and no reasonable provision was made against eventualities; hence plague, leprosy, and famine played havoc among the Christian hosts. The institution of quasi-religious orders of knighthood, however, did much to redeem these ill-starred expeditions from absolute chaos.

The formation of these religious military orders was an outcome of the proselytising zeal of the earlier “middle ages,” brought into play by the first crusade. The movement was, to some extent, a fusion of the Church with the military caste for warring against the infidel for the recovery of the Holy Sepulchre. A living faith, boundless devotion, and self-sacrifice characterised these orders in the early42 stages of their existence, and the principles of charity and humility were strictly enjoined and practised with all men except the infidel, against whom they waged a pitiless war, not only in the East but in Europe also. The Grand Master of the order of St. Lazarus was always chosen from among lepers. The vows of chastity, poverty, and obedience soon, however, became “more honoured in the breach than in the observance;” and as these orders became rich, luxurious, and powerful, they began to nourish ambitions and practices quite at variance with the principles under which they were instituted. As their machinations began to be directed against all authority, and even against thrones and religion itself, they were deprived of many of their privileges, and some were suppressed altogether.

The shoulder-pieces called “ailettes” first appeared in France. They were in use in England late in the thirteenth century, but, as they fell into disuse in the fourteenth, there are not likely to be any actual examples preserved, and they rarely occur on monuments. These pieces assume various shapes, but the usual one is a rectangular figure, longer than it is broad, standing over the shoulders horizontally, perpendicularly, or diagonally, rising either in front or from behind; there are, however, instances of their being round, pentagonal, and lozenge formed. The use of these curious appendages is not very apparent, but the most natural explanation is that they were applied as a defence against strokes glancing off the helmet. They were usually ensigned with a device or crest; and, when worn in front, were often large enough to protect the armpits, instead of palettes or rondelles. They are mentioned in the roll of purchases for the Windsor tournament in 1278. There is an interesting letter in the Proceedings of the Newcastle Society of Antiquaries, vol. iv., p. 268, concerning these somewhat puzzling pieces of armour. It is addressed to Dr. Hodgkin,43 by Captain Orde Browne. The writer refers to the ailettes which he noticed on the effigy of Peter le Marechal, in the cathedral church of St. Nicholas, Newcastle. This highly interesting figure lies immediately behind the monument to Dr. Bruce. Captain Orde Browne mentions examples of ailettes in the churches of Ash, Clehongre in Herefordshire, and Tew in Oxfordshire, and quotes two authorities who state that these three are the only churches in which effigies with these appendages have been found; the names, however, have not been preserved in the letter. At all events, the authorities in question had overlooked the Newcastle example, on the shield of which there seems to be a bend. We refer to this effigy as attributed to Peter le Marechal. Brand believed it to be the effigy of the founder of St. Margaret’s chantry, Peter de Manley, a baron who bore, according to Guillim, “or,” a bend sable. He was associated with the Bishop of Durham, and others, for guarding the East Marches, and died in 1383. His arms therefore correspond with those on the shield of the effigy. The late Mr. Longstaffe, however, ascribes the figure to Peter le Marechal, who died in 1322.

As to the question between Peter de Manley and Peter le Marechal there can be no doubt whatever, as the presence of ailettes, and the general character of the armour, undoubtedly date the figure about the end of the thirteenth century or very early in the fourteenth, and there is an interval of sixty-one years between the deaths of the two knights. Peter le Marechal was sword-bearer to Edward I., and is buried in St. Nicholas’s Church. It appears from the king’s wardrobe account that a sword was placed on the body by the king’s command. According to M. Viollet le Duc, this innovation, the employment of ailettes, dates from the end of the thirteenth century, but M. Victor Gay cites an example of the employment of ailettes in 1274. There is, however,44 one of a still earlier date, occurring in a MS. dated 1262, in which is a figure of Georges de Niverlee. This manuscript does not say where this figure is or was. There is an ailette on the right shoulder only, and we may possibly infer that this piece was first used singly. A very interesting example of this kind occurs on an illumination on the psalter executed for Sir Geoffrey Loutterell, who died in 1345; and the single ailette bears his arms, “azure,” a bend between six martlets “argent.” We see from the roll of purchases made for the tournament of Windsor Park (1278) that the ailettes specified for were to be of leather and carda.11 Ailettes were worn by Sir Roger de Trumpington in the Windsor tournament, but these were of leather; and are figured on his monumental brass rising from behind the shoulders. An incised monumental slab in the church of St. Denis, Gotheim, Belgium, shows a figure of Nenkinus de Gotheim (1296) with these appendages. These are remarkable for their diagonal pose. If any device existed it has been worn off. There is an example of another Gotheim (1307) charged with a rose, and a couple in the Porte de Hal Museum, at Brussels, dated 1318 and 1331 respectively. A very elaborate pair of ailettes appears in the inventory of Piers Gaveston (1313): “les alettes garniz et frettez de perles.” There is a German example on the statue of Rudolph von Hierstein at Bâle (died 1318).

Helms with horns were worn by the Vikings, and in all probability the headpiece with these appendages45 dredged up with a shield in the Thames, and now deposited in the British Museum, is of early Scandinavian origin. Horned helms were probably originally emblematic of the goddess Hathor or Isis, and came to Northern Europe through the Greeks. A helm with horns, about B.C. 3750, found at Susa, has been already referred to in Part I. We have an example of an Etruscan helm with horns, and Meyrick says that such were worn by the Phrygians, though rarely. Diodorus Siculus refers to this form as used by the Belgic Gauls. There are instances of helms with horns as late as the fourteenth and even fifteenth centuries. One occurs on the tomb of Diether von Hael, at Borfe, in the Tyrol, near Moran. This helm has ears as well as horns. The warrior died 1368. Other examples, one on the effigy of Burkhard von Steenberg (died 1379), in the Museum at Hildesheim, and another on that of Gottfried von Furstenberg (died 1341), in the Church of Hasbach; and there is a grotesque helmet in the Tower of London, presented to Henry VIII. by the Emperor Maximilian, with ram’s horns; and such appendages were sometimes used on chanfreins of the sixteenth century—there are examples at Madrid and Berlin. The early Anglo-Saxons wore four-cornered helms with a fluted comb-like crest.

The great variety in mediæval and renaissance headgear is somewhat bewildering, but it may all be brought down to a few types with certain salient characteristics, which, however, greatly interweave. The knights of chivalry, or their armour-smiths, seem to have given as great a rein to their fancy and imagination as the constructors of feminine headgear of all time; still the change and application of weapons of attack played the most important part in the constant modifications of warlike headpieces, as of other defensive armour.

Both Normans and Anglo-Saxons used the word46 “helm”12 (of Gothic or Scandinavian derivation) in the eleventh century, as applied to the conical steel cap with the nasal then in use. The equivalent in French was “heaume.” The word “helmet” is of course the diminutive of “helm,” and is specially applied to the close-fitting casques, first used in the fifteenth century, of which more anon. The seal of Henry I. shows that monarch as wearing a conical helm.

The form of helm of the Bayeux tapestry is a quadrilateral pyramid with a narrow strip of iron extending over the nose; but this nasal is but rarely met with after the twelfth century, although it occurs in every century up to the seventeenth. The Norman helm was probably wholly of iron, and sometimes had a neckpiece.

The great helm or heaume, without a movable visor, is of English origin. It first appeared about the middle of the twelfth century, and was worn over a hood of mail, which was then found inadequate to resist either the lance or a heavy blow from a battle-axe or mace, or even a stroke from the then greatly improved sword. The helm had the effect of distributing the force of the blow, and to a certain extent parried it. The second seal of Richard I. shows him in a great helm, which is either flat-topped or conical, with the nasal, and is obviously derived from the antique. The cylindrical or flat-topped variety came into vogue towards the end of the twelfth century. There is an example of the conical form in the Museum of Artillery at Paris, and one of the nearly flat-topped variety, rising very slightly towards the centre, in the Tower of London. The great helm is often represented as a pillow for the head in effigies.

The next form, which is in great variety, the knight’s early tilting helm, was used pre-eminently for jousting; the visored bassinet being worn generally in battle. It was introduced to resist the heavy lance47 charge. This form was hemispherical, conical, or cylindrical, with an aventail to cover the face,13 and ocularia or slits for vision, and sometimes a guard for the back of the neck. Breathing holes first appear early in the reign of Henry III. It formed a very heavy single structure, sometimes with bands of iron in front constituting a cross; and in the earlier forms the head bore the whole weight; but later it was constructed to rest on the shoulders, and the crossbands disappeared. It was fastened to the saddle-bow when not in use. The movable aventail appears on the second seal of Henry III. An excellent example may be seen on the male effigy in Whitworth Churchyard, which is described in the Proceedings of the Newcastle-upon-Tyne Society of Antiquaries, vol. iv., p. 250. This monument shows two recumbent figures—male and female. We are concerned with the male effigy, and have the authority of Mr. Longstaffe that it represented a member of the family of Humez of Brancepeth. The character of the armour would indicate a date in the second quarter of the thirteenth century. The helm is cylindrical and flat-topped. There are two other north-country effigies of about the same date, one at Pittington, the helmet of which is round-topped, and the other at Chester-le-Street (both in the county of Durham). The round-topped helm appeared late in the thirteenth century. A very early thirteenth century helm may be seen on an effigy in Staunton Church, Nottingham, and a flat-topped cylindrical specimen surmounts the figure on the curious water ewer shown in Plate XXII. of Archæologia Æliana, vol. iv. (O.S.). There are instances of this form as early as the last quarter of the twelfth century.

De Cosson gives drawings of several of these helms in his resumé of the specimens exhibited in 1880 (for48 which see Proceedings of the Royal Archæological Institute). That on the seal of Henry III. has breathing holes, and that of Edward II. shows his helm to have been cylindrical, with a grated aventail. Helms at this period were sometimes made of brass. The helm formerly hanging over the tomb of Sir Richard Pembridge, K.G., in the nave of Hereford Cathedral, and now in the possession of Sir Noel Paton,14 is a good example of the reign of Edward III. This helm has been minutely described by De Cosson in his catalogue of the helmets already referred to. The great jousting helm of the fifteenth century will be described later. The bassinet, lined with leather, basin-shaped as its name implies, was lighter and close fitting; and in England usually provided with staples for a camail. It was often used under a crested helm of large size, but, as mentioned before, when the bassinet became visored it was worn heavier, and then largely superseded the great helm. The bassinet was generally worn in England in the fourteenth century and late in the preceding. This helmet is more fully described later.

The chapel-de-fer is an iron helmet of the twelfth century, with or without a broad brim. It was often holed for a camail, and was worn sometimes under a hood of mail. The one without brim is often termed a chapeline, and is, we take it, the small bassinet. Illustrations of two great helms at the Zeughaus, Berlin, are given in Fig. 2.

It was late in the reign of Edward II. when considerable progress was made in the direction of full49 “plain” armour in England, but, as shown in the section headed “Chain-mail,” etc., the use of the standard of mail survived until the beginning of the fifteenth century and even later. It is, in fact, impossible to lay down any arbitrary dates, or anything like a clear line of demarcation in respect to the relative proportions of chain and plate armour in use by English men-at-arms up to the beginning of the fifteenth century; but the fortunate preservation in our churches of the remarkable series of effigies and monumental brasses helps us greatly. There is, however, very little evidence of this kind before the middle of the thirteenth century. Breastplates, as distinguished from the old plastrons-de-fer, were to be met with early in the reign of Edward II., but the general rule was still a hauberk of mail, with épaulières, coudières of plate, and some splint plates on the arms, all fastened with straps and buckles; the legs were still generally encased in mail, with, of course, genouillières at the knees.

Fig. 2.—Great Helms at Berlin.

1250–1300. 1350–1400.

The long reign of Edward III. (1327–77) saw great strides towards the general use of full plate armour. An illumination on the psalter of Sir Geoffrey Loutterell (died 1345) furnishes an interesting example of the time. The knight is on horseback, sheathed in plate; he wears the pointed bassinet, a rectangular ailette on his right shoulder. His coat-of-arms (“azure,” a bend between six martlets “argent”) is repeated wherever possible: on the ailette, helm, pennon, shield, and housings; and again on the dress of a lady who is handing up the helm. Another lady holds the shield: her dress impales “azure,” a bend “or,” a label “argent” for Scrope of Masham. The saddle is the “well,” and the spurs rowelled. The lance-rest (an adjustable hook of iron for supporting the lance shaft) was introduced about 1360. A brass of Sir John Lowe, at Battle, Sussex, gives a good idea of the armour prevailing late in the reign of Richard II. and in that of Henry IV. The surcoat is50 omitted, so that in this instance the whole front panoply is exposed to view, though the garment continues to appear occasionally on monuments well into the fifteenth century, as shown on the brass of Sir William de Tendering in Stoke-by-Nayland Church (1408). The bassinet becomes less acutely pointed than on the effigy of the Black Prince. Épaulières show articulations, and gauntlets are articulated at the fingers. This is the case on the brass of Sir John Lowe, where the armpits are protected by rondelles, and the now visible taces of steel hoops form a skirt of from six to eight laminations. The cuisse is articulated, and the sollerets are “à la poulaine,” though not in the extreme form. The spurs are of the rowel type, and the figure is armed with sword and dagger.

Full plate armour was used in Germany and Italy earlier than in England. There is ample evidence of this, but care must be taken in sifting the testimony of old “Chronicles.” In the “Tristan and Isolde” MS., by Godfrey of Strasburg, of the second half of the thirteenth century, the German men-at-arms are represented in “white” armour; helms with the bevor attached to the cuirass, the upper part of the face open, jambs of plate and sollerets “à la poulaine.” Their horses appear with bards. A statute of Florence of the year 1315 is remarkable for the following statement, viz.:—“Every knight to have a helm, breastplate, gauntlets, cuisses, and jambs, all of iron!”

These manuscripts, however, must not be taken as conclusive. On the contrary, they really represent what is now considered to be a late stage of mixed armour. An Italian example figured in Hewitt (Plate XXVII.) shows the statue of a knight in a church at Naples (1335). He wears a hauberk of mail, with rondelles at the shoulders and elbows, rounded plates strapped over the upper arm, and jambs of iron. The sollerets are in chain-mail. The heavy horsemen of the “middle ages”51 are often referred to as “knights,” but of course there could only be a very small percentage of them enjoying that degree. Presumably many were eligible for the honour of knighthood for marked bravery in the field.

Before the use of gunpowder in warfare the baronial fortress was almost impregnable, but cannon turned the tables on the feudal nobility, dealing a severe blow at extreme feudalism, of which these castles were the invariable centres.