You will remember, gentlemen, that when I was interrupted, I was about to follow John

Smith on his march with Captain M’Taggart. Well, you see, Prince Charles Edward chanced

to be at this time at Kilravock Castle, the ancient seat of the Roses. Thither the

sagacious captain thought it good policy to present himself, with the motley company,

the greater number of the individuals of which he had himself collected. There he

received his due meed of praise for his zeal, with large promises of future preferment

for his energetic exertions in the Prince’s cause. But although the Captain [74]thus took especial care to serve himself in the first place, he made a point of strictly

keeping his own promise to John Smith, for he did present him to the Prince, along

with some five or six other recruits, whom he had cajoled to follow him, somewhat

in the way he had cajoled John. But this their presentation was more with a view of

enhancing the value of his own zeal and services, for his own private ends, than for

the purpose, or with the hope of benefiting them in any way. The Prince came out to

the lawn with M’Taggart, and some of his own immediate attendants. The men were presented

to him by name; and John Smith was especially noticed by him. He spoke to each of

them in succession; and then, clapping John familiarly on the shoulder,—

“My brave fellows,” said he, “you have a glorious career before you. The enemy advances

into our very hands. I trust we shall soon have an opportunity of fighting together,

side by side. Meanwhile, go, join the gallant army which I have so lately left at

Culloden, eagerly waiting the approach of our foes. I shall see you very [75]soon, and I shall not forget you.” So saying, he took off his Highland bonnet; and,

whilst a gentle zephyr sported and played with his fair curls, he bowed gracefully

to the men, and then retired into the house.

“She’s fichts to ta last trap o’ her bluids for ta ponny Princey!” cried John, with

an enthusiasm which was cordially responded to by shouts from all present.

M’Taggart then gave the word, and the party wheeled off on their march in the direction

of Inverness, in the vicinity of which town the Prince’s army was encamped. Their

way lay down through the parish of Petty, and past Castle-Stuart. As they moved on,

they were every where loudly cheered by the populace—men, women, and children, who

turned out to meet them, and showered praises and blessings upon them; and this friendly

welcome seemed to await them all along their route, till they joined the main body

of their forces, which lay about and above the mansion house of Culloden.

John Smith would have much preferred to [76]have placed himself under the standard of the Mackintosh, whom the Smiths or Gowe,

the descendants of the celebrated Gowin Cromb, who fought on the Inch of Perth, held

to be their chief, as head of the Clan-Chattan. But M’Taggart was unwilling to lose

the personal support of so promising a soldier. Perhaps also he began to feel a certain

interest in the young man; and he accordingly advised him to stick close to him at

all times.

“Stick you by me, John,” said he—“stick close by my side; I shall then be able to

see what you do, as well as to give a fair and honest, and I trust not unfavourable

report of the gallant deeds which your brave spirit may prompt you to perform. Depend

upon it, with my frequent opportunities of obtaining access to the Prince, I can do

as much good for you, at least, as any Mackintosh.”

On the night of the 14th of April then, John Smith lay with M’Taggart and his company,

among the whin and juniper bushes in the wood of Culloden, where the greater part

of the Jacobite army that night disposed of themselves. [77]Whatever might have been the ill-provided state of the other portions of the Prince’s

troops, that with which John was now consorted, had no reason to complain of any want

of those refreshments which human nature requires, and which are so important to soldiers.

Large fires were speedily kindled; and the Pensassenach’s great sow, with all her

little pigs, and the poor woman’s poultry of all kinds, together with some few similar

delicacies which had elsewhere been picked up here and there, were soon divided, and

prepared to undergo such rude cookery as each individual could command; and these,

with the bread and cheese, and other such provisions, which they had carried off from

the Pensassenach, as well as from some other houses, enabled them to spread for themselves

what might be called a vurra liberal table in the wilderness. But the savoury odour

which their culinary operations diffused around, brought hungry Highlanders from every

quarter of the wood, like wolves upon them, so that each man of their party was fain

to gobble up as much as he could swallow in haste, lest he should fail to [78]secure to himself enough to satisfy his hunger, ere the whole feast should disappear

under the active jaws of those intruders. The liquor was more under their own control.

The flask was allowed to circulate through the hands of those only to whom it most

properly belonged by the right of capture. John, for his part, had a good tasse of

the Pensassenach’s brandy; and the smack did not seem to savour the worse within his

lips, because it was prefaced with the toast of—“Success to the Prince, and confusion

to the Duke of Cumberland!”

After this their refreshment, the men and officers disposed themselves to sleep around

the fires of their bivouac, each in a natural bed of his own selection, John Smith,

being a pious young man, retired under the shelter of a large juniper bush, and having

there offered up his evening prayer to God, he wrapped himself up in his plaid, and

consigned himself to sleep. How long he had slept he knew not; when, as he turned

in his lair to change his position, his eye caught a dim human figure, which floated,

as it were, in the air, stiff and erect, immediately [79]under the high projecting limb of a great fir tree, that grew at some twenty paces

distant from the spot where he lay. The figure seemed to have a preternatural power

of supporting itself; and as the breeze wailed and moaned through the boughs, it appeared

alternately to advance and to recede again with a slow tremulous motion. John’s heart,

stout as it was against every thing of earthly mould, began to beat quick, and finally

to thump against his very ribs, with all manner of superstitious fears. He gazed and

trembled, without the power of rising, which he would have fain done, not for the

purpose of investigating the mystery, but to take the wiser course of looking out

for some other place of repose, where he might hope to escape from the appalling contemplation

of this strange and most unaccountable apparition. He lay staring then at it in a

cold sweat of fright, whilst the faint glimmering light from the nearest fire, as

it rose or fell, now made it somewhat more visible, and now again somewhat more dim.

At length, an accidental fall of some of the half burnt fuel, sent up a transient

gleam that fully illuminated [80]the ghastly countenance of the spectre, when, to John’s horror, he recognised the

pale and corpse-like features of Mr. William Dallas, the packman, whom he had left

so ingeniously inserted into the sack, and deposited in the Pensassenach’s lint-pot.

Though the gag was gone, the mouth was wide open, and the large, protruded, and glazed

eye-balls, glared fearfully upon him. Though the light was not sufficient to display

the figure correctly, John’s fancy made him vividly behold the sack. He would have

spoken if he could; but he felt that the apparition of a murdered man was floating

before him. His throat grew dry of a sudden. He gasped—but could not utter a word.

He doubted not that the packman had been forgotten by Morag, and that, having fallen

down into the water through cold and exhaustion, the wretch had at last miserably

perished; and he came very naturally to the conclusion, that he who had put the unfortunate

man there, was now doomed to be henceforth continually haunted by his ghost. Fain

would he have shut out this horrible sight, by closing his eyes, or by drawing his

plaid over [81]them; but this he was afraid to do, lest the object of his dread should swim towards

him through the air, and congeal his very life’s-blood by its freezing touch. Much

as he loved Morag, he had some difficulty in refraining from inwardly cursing her,

for her supposed neglect of his express injunctions to relieve the packman from the

pool. As he stared on this dreadful apparition, the flickering gleam from the faggot

sunk again, and the countenance again grew dim; but John seemed still to see it in

all its intensity of illumination. No more rest had he that night. Still, as he gazed

on the figure, he again and again fancied that he saw it gradually and silently gliding

nearer and nearer to him. The only relief he had was in fervent and earnest prayers,

which he confusedly murmured, from time to time, in Gaelic. He eagerly petitioned

for daylight, hoping that the morning air might remove all such unrealities from the

earth. At length, the eastern horizon began to give forth the partial glimmer of dawn;

but John was somewhat surprised to find, that, instead of the [82]apparition fading away before it, the outlines of its horrible figure became gradually

more and more distinct as it advanced, until even the features were by degrees rendered

visible. But although John, by this time, began to discover that his fancy had supplied

the sack, he now perceived something which he had not been able to see before, and

that was, a thin rope which hung down from the horizontal limb of the fir tree, and

suspended, by its lower extremity, the body of the poor packman by the neck. John

was much shocked by this discovery. But he could not help thanking God that he was

thus acquitted of the wretched man’s death; and after the misery that he had suffered

from the supposed presence of the apparition of a man who had been drowned through

his means, however innocently, the relief he now experienced was immense. He called

up some of his comrades to explain the mystery; and from them he learned, that Mr.

Dallas had been caught in the early part of the night, in the very act of attempting

to carry off Captain M’Taggart’s [83]horse from its piquet, and that he had been instantly tucked up to the bough of the

fir tree, without even the ceremony of a trial.

The young Prince Charley was in the field by an early hour on the morning of the 15th,

and being all alive to the critical nature of his circumstances, and by no means certain

as yet how near the enemy might by this time be to him, he judged it important to

collect, and to draw up his army on the most favourable ground he could find in the

neighbourhood. He therefore marched them up the high, partly flattish, and partly

sloping ridge, which, though commonly called Culloden Moor, from its being situated

immediately above the house and grounds of that place, has in reality the name of

Drummossie. He led them to a part of this ground, a little to the south eastward of

their previous position in the wood of Culloden, and there he drew them up in order

of battle. There they were most injudiciously kept lying on their arms the whole day,

and if Captain M’Taggart’s men had feasted tolerably well the previous night, their

commons were any thing but plentiful during the time they [84]occupied that position. It was not in the nature of things, that subordination could

be so strictly preserved in the Prince’s army, as it was in that of the Duke of Cumberland.

I, who am well practeesed in the discipline of boys, gentlemen, know very well that

it would be impossible to bring a regiment of them under immediate command, if the

individuals composing it were to be collected together all at once, raw and untaught,

from different parts of the district. It is only by bringing one or two at a time,

into the already great disciplined mass, that either a schoolmaster, or a field-marischal

can promise to have his troops always well under control. By the time evening came,

the officers, as well as the men of the Prince’s army, began to suffer under the resistless

orders of a commander to whom no human being can say nay. Hunger, I may say, was rugging at their vurra hearts, and as they all saw, or supposed that they saw, reason to

believe that there was no chance of the enemy coming upon them that night, many of

them went off to Inverness and elsewhere, in search of food. M’Taggart himself could

not resist those internal [85]admonitions, which his stomach was so urgently giving him from time to time, and accordingly,

John Smith conceived he was guilty of no great dereliction of duty, in strictly following

the first order which his captain had given him, viz., to “stick by his side,” which

he at once resolved to do, as he saw him go off to look for something to support nature.

But the captain and his man had hardly got a quarter of a mile on the road to Inverness,

when they, with other stragglers, were called back by a mounted officer, who was sent,

with all speed, after them, to tell them that they must return, in order to march

immediately. The object of their march was that ill-conceived, worse managed, and

most unlucky expedition for a night attack on the Duke of Cumberland’s camp at Nairn,

which had that evening been so hastily planned. Hungry as they were they had no choice

but to obey, and accordingly they hurried to their standards. The word was given,

and after having been harassed by marching all night, without food or refreshment

of any kind, they at last got only near enough to Nairn [86]just to enable them to discover that day must infallibly break before they could reach

the enemy’s camp, and that consequently no surprise could possibly take place. Disheartened

by this failure, they were led back to their ground, where they arrived in so very

faint and jaded a condition, that even to go in search of food was beyond their strength,

so that they sank down in irregular groups over the field, and fell asleep for a time.

Awakened by hunger after a very brief slumber, they arose to forage. M’Taggart, and

some of his party, and John Smith amongst the rest, went prowling across the river

Nairn, which ran to the south of their position, and there they caught and killed

a sheep. They soon managed to kindle a fire, and to subdivide the animal into fragments,

but ere each man had time to broil his morsel, an alarm was given from their camp.

Like ravenous savages they tore up and devoured as much of the half raw flesh as haste

would allow them to swallow, and hurrying back, they reached their post about eight

o’clock in the morning, when they found that the Duke of Cumberland was approaching

with his army in full march.

[87]

The position chosen by the Prince as that where he was to make his stand on that memorable

day, the 16th of April, was by no means very wisely or very well selected. It was

a little way to the westward of that which his army had occupied on the previous day.

Somewhat in advance, and to the right of his ground, there stood the walls of an enclosure,

which the experienced eye of Lord George Murray soon enabled him to perceive, and

he was at once so convinced that they presented too advantageous a cover to the assailing

enemy, to be neglected by them, that he would fain have moved forward with a party

to have broken them down, had time remained to have enabled him to have effected his

purpose. But the Duke of Cumberland’s army was already in sight, advancing in three

columns, steadily over the heath, from Dalcross Castle, the tower of which was seen

rising towards its eastern extremity. The Highlanders were at this time dwindled to

a mere handful, and some of the best friends of the cause of the Stewarts who were

present, and perhaps even the young Prince himself, began to [88]believe that he had been traitorously deserted. But the alarm had no sooner been fully

spread by the clang of the pipes, and the shrill notes of the bugles, than small and

irregular streams of armed men, in various coloured tartans, were seen rushing towards

their common position, like mountain rills towards some Highland lake, and filling

up the vacant ranks with all manner of expedition. Many a brave fellow, who had gone

to look for something to satisfy the craving of an empty stomach, came hurrying back

with as great a void as he had carried away with him, because he preferred fighting

for him whom he conscientiously believed to be his king, to remaining ingloriously

to subdue that hunger which was absolutely consuming him. No one was wilfully absent

who could possibly contrive to be present, but yet the urgent demands of the demon

of starvation, to which many of them had yielded, had very considerably thinned their

numbers, and, in addition to this source of weakness, there was another obvious one,

arising from the physical strength of those who were present being wofully diminished

by the want they had endured, [89]and the fatigue they had undergone. But with all these disadvantages the heroic souls

of those who were on the field remained firm and resolute.

John Smith’s military knowledge was then too small to allow him to form any judgment

of the state of affairs, far less to enable him to carry off, or to describe, any

thing like the general arrangement of the order of battle on both sides. He could

not even tell very well what regiments his corps was posted with: he only knew this,

that according to the order he had received he stuck close to Captain M’Taggart. He

always remembered with enthusiasm, indeed, that the Prince rode through the ranks

with his attendants, doing all that he could to encourage his men, and that when he

passed by where John himself stood, he smiled on him like an angel, and bid him do

his duty like a man.

“Och, hoch!” cried John, with an exultation, which arose from the circumstance of

his not being in the least aware that every individual near him had, like him, flattered

himself that he was the person so distinguished.—“Fa wad hae soughts tat ta ponny

Princey wad hae [90]mindit on poor Shon Smiss? Fod, but she wad fichts for her till she was cut to collops!”

But John had little opportunity of fighting, though he appears to have borne plenty

of the brunt of the battle. There were two cannons placed in each space between the

battalions composing the first line of the Duke of Cumberland’s army, and these were

so well served as to create a fearful carnage among the Highland ranks. To this dreadful

discharge John Smith stood exposed, with men falling by dozens around him, mutilated

and mashed, and exhibiting death in all his most horrible forms, till, to use his

own very expressive words,—“She was bitin’ her ain lips for angher tat she could not

get at tem.” But before John could get at them, the English dragoons, who, under cover

of the walls of the enclosure I have mentioned, had advanced by the right of the Highland

army, finally broke through the fence, and getting in behind their first line, came

cutting and slashing on their backs, whilst the Campbells were attacking them in front,

and mowing them down like grass. Then, indeed, did the melée become desperate, [91]and then was it that John began to bestir himself in earnest. Throwing away his plaid,

and the little bundle that it contained, he dealt deadly blows with his broad-sword,

everywhere around him. He fought with the bravery and the perseverance of a hero.

At length his bonnet was knocked from his head, and although he was still possessed

with the most anxious desire to obey Captain M’Taggart’s order to stick to his side,

he was surprised on looking about him to find that there was no M’Taggart, no, nor

any one else left near him to stick to but enemies.

John Smith’s spirit was undaunted, so that, seeing he had no one else to stick to,

he now resolved to stick to his foes, to the last drop of life’s blood that was within

him. Furiously and fatally did he cut and thrust, and turn and cut and thrust again,

at all who opposed him; but he was so overwhelmed by opponents, that in the midst

of the blood, and wounds, and death which he was thus dealing in all directions, he

received a desperate sabre cut, which, descending on him from above, entirely across

[92]the crown of his bared head, felled him instantaneously to the ground, and stretched

him senseless among the heather, whilst a deluge of blood poured from the wound over

both his eyes.

When John began partially to recover, he rubbed the half-congealed blood from his

eyelids with the back of his left hand, and looking up and seeing that the ground

was somewhat clear around him, he griped his claymore firmly with his right hand,

and raising himself to his feet, he began to run as fast as his weak state would allow

him. He thought that he ran in the direction of Strath Nairn, and he ran whilst he

had the least strength to run, or the least power remaining in him. But his ideas

soon became confused, and the blood from the terrible gash athwart his head trickled

so fast into his eyes, that it was continually obscuring his vision. At length he

came to a large, deep irregular hollow hag, or ditch, in a piece of moss ground, which

had been cut out for peats, and there, his brain beginning to spin round, he sank

down into the moist bottom of it to die, and as the tide of life flowed fast from

him, he [93]was soon lost to all consciousness of the things or events of this world.

Whilst John was lying in this senseless state, he was recognised by one of the fugitives,

who, in making his own escape, chanced to pass by the edge of the ditch in the moss

where the poor man lay. This was a certain Donald Murdoch, who had long burned with

a hopeless flame for black-eyed Morag. With a satisfaction that seemed to make him

forget his present jeopardy in the contemplation of the death of his rival, he looked

down from the edge of the peat hag upon the pale and bloody corpse, and grinned with

a fiendish joy.

“Ha! there you lie!” cried he in bitter Gaelic soliloquy.—“The fiend a bit sorry am

I to see you so. You’ll fling or dance no more, else I’m mistaken.—Stay!—is not that

the bit of blue ribbon that Morag tied round his neck, the last time that we had a

dance in the barn? I’ll secure that, it may be of some use to me;” and so saying he

let himself down into the peat hag, hastily undid the piece of ribbon,—and [94]then continued his flight with all manner of expedition.

Following the downward course of the river Nairn, running at one time, and ducking

and diving into bushes, and behind walls at another, to avoid the stragglers who were

in pursuit, he by degrees gained some miles of distance from the fatal field, and

coming to a little brook, he ventured to halt for a moment, to quench his raging thirst.

As he lay gulping down the crystal fluid, he was startled by hearing his own name,

and by being addressed in Gaelic.

“Donald Murdoch!—Oh, Donald Murdoch, can you tell me is John Smith safe? Oh, those

fearful cannons how they thundered!—Oh, tell me, is John Smith safe?—Oh, tell me!

tell me!”

“Morag!” cried Donald, much surprised, but very much relieved to find that it was

no one whom he had any cause to be afraid of,—“Morag!—What brought you so far from

home on such a day as this?”

“Oh Donald!” replied Morag, “I came to [95]look after John Smith;—oh, grant that he be safe!”

“Safe enough, Morag,” replied Donald, galled by jealousy. “I’ll warrant nothing in

this world will harm him now.”

“What say you?” cried Morag. “Oh, tell me! tell me truly if he be safe?”

“I saw John Smith lying dead in a moss hole, his skull cleft by a dragoon’s sword,”

replied Donald with malicious coolness.

“What?” cried Morag, wringing her hands, “John Smith dead! But no! it is impossible!—and

you are a lying loon, that would try to deceive me, by telling me what I well enough

know you would wish to be true. God forgive you, Donald, for such cruel knavery!”

“Thanks to ye, Morag, for your civility,” replied Donald Murdoch calmly; “but if you

wont believe me, believe that bit of ribbon—see, the very bit of blue ribbon you tied

round John Smith’s neck, the night you last so slighted me at the dance in the barn.

See, it is partly died red in his life’s blood.”

“It is the ribbon!” cried Morag, snatching [96]it from his hand with excessive agitation, and kissing it over and over again, and

then bursting into tears. “Alas! alas! it must be too true! What will become of poor

Morag!—why did I not go with him! What is this world to poor desolate Morag now?—And

yet—he may be but wounded after all. It must be so—he cannot be killed. Where did

you leave him?—quick, tell me!—oh, tell me, Donald. Why do we tarry here? let us forward

and seek him!—there may be life in him yet, and whilst there is life there is hope.

Let me pass, Donald; I will fly to seek him!”

“I love you too well to let you pass on so foolish and dangerous an errand,” said

Donald, endeavouring to detain her. “I tell you that John Smith is dead; but you know,

Morag, you will always find a friend and a lover in me. So think no more——”

“I will pass, Donald,” cried Morag, interrupting him, and making a determined attempt

to rush past him.

“That you shall not,” replied Donald, catching her in his arms.

[97]

“Help, help!” cried Morag, struggling with all her might, and with great vigour too,

against his exertions to hold her.

At this moment the trampling of a horse was heard, and a mounted dragoon came cantering

down into the hollow. His sabre gleamed in the air—and Donald Murdoch fell headlong

down the bank into the little rill, his skull nearly cleft in two, and perfectly bereft

of life.

“A plague on the lousy Scot!” said the trooper, scanning the corpse of his victim

with a searching eye. “His life was not worth the taking, had it not been, that the

more of the rascally race that are put out of this world, the better for the honest

men that are to remain in it, and therefore it was in the way of my duty to cut him

down. There is nought on his beggarly carcase to benefit any one but the crows.—And

so the knave would have kissed thee against thy will, my bonny black-eyed wench. Well,

’tis no wonder thou shouldst have scorned that carotty-pated fellow; you showed your

taste in so doing, my dear: and now you shall be rewarded by having a somewhat better

sweetheart.[98]—Come!” continued he, alighting from his charger, and approaching the agitated and

panting girl—“Come, a kiss from the lips of beauty is the best reward for brave deeds;

and no one deserves this reward better than I do, for brave deeds have I this day

performed. Why do you not speak, my dear? Have you no Christian language to give me?

Can it be possible that these pretty pouting lips have no language but that of the

savages of this country?—Come, then, we must try the kissing language; I have always

found that to be well understood in all parts of the world.”

“Petter tak’ Tonald’s pig puss o’ money first,” said Morag, pointing down to the corpse

in the hollow.

“Ha! money saidst thou, my gay girl?” cried the trooper. “Who would have thought of

a purse of money being in the pouch of such a miserable rascally savage as that? But

the best apple may sometimes have the coarsest and most unpromising rhind; and so

that fellow, unseemly and wretched as he appears, may perchance have a well-lined

purse after all. If it be so, girl, I shall say that thy language is like the talk

of an angel. [99]Then do you hold the rein of this bridle, do you see, till I make sure of the coin

in the first place—best secure that, for no one can say what mischance may come; or

whether some comrade may not appear with a claim to go snacks with me. So lay hold

of the bridle, do you hear, and dont be afraid of old Canterbury, for the brute is

as quiet as a lamb.”

Morag took the bridle. The trooper descended the bank, and he had scarcely stooped

over the body to commence his search for the dead man’s supposed purse, when the active

girl, well accustomed to ride horses in all manner of ways, vaulted into the saddle,

and kicking her heels into Canterbury’s side, she was out of the hollow in a moment.

Looking over her shoulder, after she had gone some distance, she beheld the raging

dragoon puffing, storming, and swearing, and striding after her, with, what might

be called, that dignified sort of agility, to which he was enforced by the weighty

thraldom of his immense jack-boots. Bewildered by the terror and the anxiety of her

escape, she flew over the country, for some time, without knowing which [100]way she fled. At length she began to recover her recollection, so far as to enable

her to recur to the object which had prompted her to leave home. On the summit of

a knoll she checked her steed—surveyed the country,—and the whole tide of her feelings

returning upon her; she urged the animal furiously forward in the direction of the

fatal field of Culloden.

She had not proceeded far, when, on coming suddenly to the edge of a rough little

stoney ravine, she discovered five troopers refreshing themselves and their horses

from the little brook that had its course through the bottom. She reined back her

horse, with the intention of stealing round to some other point of passage; but as

she did so, a shout arose from the hollow of the dell.—She had been perceived. In

an instant the mounted riders rushed, one after another, out of the ravine, and she

had no chance of escape left her, but to ride as hard as the beast that carried her

could fly, in the very opposite direction to that which she had hitherto pursued,

for there was no other course of flight left open to her.

[101]

The five troopers were now in full chase after Morag, shouting out as they rode, and

urging on their horses to the top of their speed. The ground, though rough, stony,

and furzy, was for the most part firm enough, and the poor girl, now driven from that

purpose to which her strong attachment to John Smith had so powerfully impelled her,

and being distracted by her griefs and her fears, spared not the animal she rode,

but forced him, by every means she could employ, either by hands, limbs, or voice,

to the utmost exertion of every muscle.

“Lord, how she does ride!” said one trooper to the others; “I wish that she beant

some of them witches, as, they say, be bred in this here uncanny country of Scotland.”

“Bless you no, man,” said another; “them devils as you speak of ride on broomsticks.

Now, I’se much mistaken an’ that be not Tom Dickenson’s horse Canterbury.”

“Zounds, I believe you are right, Hall,” said another man; “but that beant no proof

that she aint a witch, for nothing but a she-devil, [102]wot can ride on a broom, could ride ould Canterbury in that ’ere fashion, I say.”

“Witch or devil, my boys, let us ketch her if we can,” shouted another.—“Hurrah! hurrah!”

“Hurrah! hurrah! hurrah!” re-echoed the others, burying their spurs in their horses’

sides, and bending forward, and grinning with very eagerness.

For several miles Morag kept the full distance she had at first gained on her pursuers,

but having got into a road, fenced by a rough stone wall upon one side, and a broad

and very deep ditch on the other, the troopers, if possible, doubled their speed,

in the full conviction that they must now very soon come up with her, and capture

her. Still Morag flew,—but as she every moment cast her eyes over one or other of

her shoulders, she was terrified to see that the troopers were visibly gaining upon

her. The road before her turned suddenly at an angle,—and she had no sooner doubled

it, than, there, to her unspeakable horror—in the very midst of the way—stood Tom

Dickenson, the [103]dismounted dragoon from whom she had taken the very charger, called Canterbury, which

she then rode. The time of the action of what followed was very brief. For an instant

she reined up her horse till he was thrown back on his haunches.—Tom Dickenson’s sword-blade

glittered in the sun.

“By the god of war, but I have you now!” cried he in a fury.

The triumphant shouts of Morag’s pursuers increased, as they neared her, and beheld

the position in which she was now placed. No weapon had she, but the large pair of

scissors that hung dangling from her side, in company with her pincushion. In desperation

she grasped the sharp-pointed implement dagger fashion, and directed old Canterbury’s

head towards the ditch. Dickenson saw her intention, and wishing to counteract it,

he rushed to the edge of the ditch. The hand of Morag which held the scissors descended

on the flank of the horse, and in defiance of his master, who stood in his way, and

the gleaming weapon with which he threatened him, old Canterbury, goaded [104]by the pain of the sharp wound inflicted on him, sprang towards the leap with a wild

energy, and despite of the cut, which deprived him of an ear, and sheared a large

slice of the skin off one side of his neck, he plunged the unlucky Tom Dickenson backwards,

swash into the water, and carried his burden fairly over the ditch.

Morag tarried not to look behind her, until she had scoured across a piece of moorish

pasture land, and then casting her eyes over one shoulder, she perceived that only

two of the troopers had cleared the ditch, and that the others had either failed in

doing so, or were engaged in hauling their half-drowned comrade out of it. The two

men who had taken the leap, however, were again hard after her, shouting as before,

and evidently gaining upon her. The moment she perceived this, she dashed into a wide

piece of mossy, boggy ground, a description of soil with which she was well acquainted.

There the chase became intricate and complicated. Now her pursuers were so near to

her, as to believe that they were on the very point of seizing her, and again some

[105]impassable obstacle would throw them quite out, and give her the advantage of them.

Various were the slips and plunges which the horses made; but ere she had threaded

through three-fourths of the snares which she met with, she had the satisfaction of

beholding one of the riders who followed her, fairly unhorsed, and hauling at the

bridle of his beast, the head and neck of which alone appeared from the slough, in

which the rest of the poor animal was engulfed. The man called loudly to his comrade,

but he was too keenly intent on the pursuit, to give heed to him. The hard ground

was near at hand, and he pushed on after Morag, who was now making towards it. She

reached it, and again she plied the points of her scissors on the heaving flanks of

old Canterbury. But she became sensible that his pace was fast flagging,—and that

the trooper was rapidly gaining on her. In despair she made towards a small patch

of natural wood.—She was already within a short distance of it. But the blowing and

snorting of the horse behind her, and the blaspheming of his rider, came every instant

[106]more distinctly upon her ear. Some fifty or an hundred yards only now lay between

her and the wood. Again, in desperation, she gave the point of the scissors to her

steed—when, all at once he stopped—staggered—and, faint with fatigue and loss of blood,

old Canterbury fell forward headlong on the grass.

“Hurrah!” cried the trooper, who was close at his heels, “witch or no witch, I think

I’ll grapple with thee now.”

He threw himself from his heaving horse, and rushed towards Morag. But she was already

on her legs, and scouring away like a hare for the covert. Jack-booted, and otherwise

encumbered as he was, the bulky trooper strode after her like a second Goliah of Gath,

devouring the way with as much expedition as he could possibly use. But Morag’s speed

was like that of the wind, and he beheld her dive in among the underwood before he

had covered half the distance.

“A very witch in rayal arnest!” exclaimed the trooper, slackening his pace in dismay

and disappointment. And then turning towards his [107]comrade, who, having by this time succeeded in extricating his horse from the slough,

was now coming cantering towards him, “Hollo, Bill!” shouted he, “I’ve run the blasted

witch home here.—Come away, man, do; for if so be that she dont arth like a badger,

or furnish herself with a new horse to her own fancy out of one of ’em ’ere broom

bushes, this covert aint so large but we must sartinly find her. So come along, man,

and be active.”

But we must now return to poor John Smith, whom we have too long left for dead in

the bottom of a peat-hag. The cold and astringent moss-water flowing about his head,

by degrees checked the effusion of his blood, and at length he began to revive.

When his senses returned to him, he gathered himself up, and leaning his back against

the perpendicular face of the peat bank above him, he drank a little water from the

hollow of his hand, and then washed away the clotted blood from his eyes. The first

object that broke upon his newly recovered vision was an English trooper riding furiously

up to him, with his [108]brandished sword. John was immediately persuaded that he was a doomed man, for he

felt that, in his case, resistance was altogether out of the question. He threw himself

on his back in the bottom of the broad deep cut in the peat-hag. The trooper came

up, and having no time to dismount, he stooped from his saddle and made one or two

ineffectual cuts at the poor man. The horse shyed at John’s bloody head as it was

raised in terror from the peat-hag, and then the animal reared back as he felt the

soft mossy ground sinking under him. The trooper was determined,—got angry, and spurred

the beast forward, but the horse became obstinate and restive. At length the trooper

succeeded in bringing him up again to the edge of the peat-hag; but just as he was

craning his neck over its brink, John, roused by desperation, pricked the creature’s

nose with the point of his claymore. It so happened that he accidentally did this,

at the very instant that the irascible trooper was giving his horse a dig with his

spurs, and the consequence of these double, though antagonist stimulis, was, that

the brute made a [109]desperate spring, and carried himself and his rider clean over the hag-ditch, John

Smith and all, and then he ran off with his master through the broken moss-ground,

scattering the heaps of drying peats to right and left, until horse and man were rolled

over and over into the plashy bog.

Uninjured, except as to his gay clothes and accoutrements, which were speedily dyed

of a rich chocolate hue, the trooper arose in a rage, and could he have by any means

safely left his horse so as to have secured his not running away, he would have charged

the dying man on foot, and so he would have very speedily sacrificed him; but dreading

to lose his charger if he should abandon him, he mounted him again, and was in the

act of returning to the attack, with the determination of putting John to death, at

all hazards, either by steel or by lead, when he was arrested by the voice of his

officer, who was then passing along a road tract, at some little distance, with a

few of his troop, and who called out to him in a loud authoritative tone, “Come away

you, Jem Barnard! Why dont you follow [110]the living? Why waste time by cutting at the dying or dead?”

On hearing this command, the trooper uttered a half-smothered curse, and unwillingly

turned to ride after his comrades, throwing back bitter execrations on John Smith

as he went. John’s tongue was otherwise employed. He used it for the better purpose

of returning thanks to that Almighty Providence who had thus so wonderfully protected

him.

After this pious mental exercise, John thought that he felt himself somewhat better.

He made a feeble effort to rise, but it was altogether abortive. The blood still continued

to flow from his head—he began to feel very faint, and a raging thirst attacked him.

Turning himself round in the peat-hag, he contrived to lap up a considerable quantity

of the moss water, which, however muddy and distasteful it might be, refreshed him

so much as to give him strength sufficient to raise himself up a little, so as to

enable him to extend the circuit of his view. He had now a moment’s leisure to look

about him, and to consider, as well as the confusion of his ideas would [111]allow him, what he had best to do. But what was his surprise and dismay to see, that

although many were yet flying in all directions, and many more pursuing after them,

whole battalions of the enemy still remained unbroken in the vicinity of the field

of battle, and that some were marching up, in close order, both to the right and left

of him. There was but little time left him for farther consideration, as one of these

battalions was so near to him, that he saw, from the course it was holding, that it

must soon march directly over the spot where he was. The first thought that struck

him was that his best plan would be to lie down and feign that he was dead. But it

immediately afterwards occurred to him that a thrust from some curious or malicious

person, who might be the bearer of one of those bayonets, which already glittered

in his eyes, might do his business even more effectually than the sword of the trooper

might have done. He became convinced that he had nothing left for it but to run. But

although he was now somewhat revived, and that the dread of death gave new strength

to exhausted nature, he felt persuaded [112]of the truth, that if his wound should continue to bleed, as it had already again

began to do, his race could not be a long one in any sense of the word, even if he

should have the wonderful luck to escape the chance of its being shortened by the

sword, bayonet, or bullet of an enemy. To give himself some small chance of life,

John, though he was no surgeon, would have fain tried some means of stanching the

blood, but he lacked all manner of materials for any such operation, and he could

only try to cover the wound very ineffectually with both hands, whilst the red stream

continued to run down through his fingers. At length, necessity, that great mother

of invention, and wisest of all teachers, enabled him to hit off in a moment, a remedy,

which, as it was the best he could have possibly adopted in his present difficult

and distressing situation, might perhaps, even on an occasion where no such embarrassment

exists, be found as valuable and effective as any other which the most favourable

circumstances could afford, or the most consummate skill devise. Stooping down, he

picked up a large mass of [113]peaty turf, of nearly a foot square, and two or three inches thick. This had been

regularly cut by the peat-diggers, but having tumbled by chance into the bottom of

the peat-hag, it had been there lying soaking till the soft unctuous matter of which

it was composed was completely saturated with water like a sponge. John proceeded

upon no certain ratio medicandi, except this, that as his life’s blood was manifestly welling fast away from him,

he thought that the wet peat would stop the flow of it, and as his head was in a burning

fever, every fibre of his scalp seemed to call out for the immediate application of

its cold and moist surface. John seized it then with avidity, and clapping it instantly

on his head, with the black soft oleaginous side of it next to the wound, and the

heathery top of it outwards, he pressed it down with great care all over his skull,

and then quickly secured it fast, by tying a coarse red handkerchief over it, the

ends of which he fastened very carefully under his chin. The outward appearance of

this strange uncouth head-gear may be easily imagined, with the heather-bush [114]rising everywhere around his head over the red tier that bound it on, and surmounting

a countenance so rueful and bloody; but the effect within was so wonderfully refreshing

and invigorating, that he felt himself almost immediately restored to comparative

strength. He started to his feet; and, being yet uncertain as to which way he should

run, he raised his head slowly over the peat-hag to reconnoitre.

Now, it happened, that, at this very moment, a couple of English foot soldiers came

straggling along, thirsting for more slaughter, and prowling about for prey and plunder.

Ere John was aware of their proximity to him, they were within a few yards of the

peat-hag. As he raised his head, he beheld them approaching with their muskets and

their bayonets reeking with gore. Believing himself to be now utterly lost, a deep

groan of despair escaped from him. The soldiers had halted suddenly on beholding the

bloody face and neck of what scarcely seemed to be a human being, with a huge overgrown

forest of heather on the head instead of hair, appearing, as it were by magic, out

of the very [115]earth. They started back, and stood for an instant transfixed to the spot by superstitious

fear.

“Waunds, Gilbert, wot is that?” cried one, his eyes staring at John with horror.

Seeing, that as he was now discovered, his only chance lay in working upon that dread

which he saw that he had already excited, John first gradually drew down his head

below the bank, and then again raised it slowly and portentously, and uttered another

groan more deep and ghostly and prolonged than the first. The effect was instantaneous.

“Oh Lord! oh Lord! one of them Highland warlocks of the bog, wot dewours men, women,

and children!” cried Gilbert. “Fly—fly, Warner, for dear life!”

Off he ran, and his comrade staid not to question farther, but darted away after him,

and John had the satisfaction to see the two heroes, from whom he had looked for nothing

but sudden death, scouring away over the field, and hardly daring to look behind them.

John Smith was considerably emboldened by [116]the discovery that his appearance was so formidable to his foes. He again applied

himself to the consideration of the question as to which way it was best for him to

fly. He cast his eyes all over the field of action around him; and, much to his satisfaction,

he perceived that the officer at the head of the red regiment of Englishmen, which

had previously given him so much alarm, had been so very obliging as to determine

this difficult question for him. Some movement of the flying clans, who had retreated

on Strath Nairn, had induced the officer to alter his line of march; and, in a very

short time, John had the happiness of seeing himself very much in the rear of the

red battalion, instead of being immediately in its front, as he had formerly been.

Looking to the north-eastward, he perceived that all was comparatively clear and quiet,

so far as he could see. There were now no longer any regular masses of men on the

field, neither were there any signs of flight or pursuit in that direction. A few

stragglers were to be seen, it is true, moving about, like evil spirits among the

killed, and [117]perhaps performing the office of messengers of death to the wounded. Strange, indeed,

was the change that had taken place, upon that which had been so lately a scene of

stormy and desperate conflict. A few large birds of prey were soaring high in air,

in eager contemplation of that banquet which had been so liberally spread for them

on the plain by ferocious man. But, in the immediate neighbourhood of the spot where

John Smith was, the terrified pewit had already settled down again with confidence

on her nest, the robin had again begun to chirp, and to direct his sharp eye towards

the earth in search of worms; and the lark was again heaving herself up into the sky,

giving forth her innocent song as she rose,—all apparently utterly unconscious that

any such terrible and bloody turmoil had taken place between different sections of

the human race. John therefore made up his mind at once; and, scrambling out of the

peat-hag, he darted away over the moor, and flying like a ghost across the very middle

of the field of battle, through the heaps of dead and dying, to the utter terror and

discomfiture [118]of those wolves and hyenas in the shape of men—aye, and of women too—who were preying,

as well upon those who had life, as upon those who were lifeless, he scattered them

to right and left in terror at his appalling appearance, and dived amid the thick

woods of Culloden.

Having once found shelter among the trees, John stopped to breathe awhile, and then

he again set forward to unravel his way. It so happened, that, as he proceeded, he

chanced to come upon the very spot where he had feasted with MacTaggart and his comrades

on his mistress the Pensassenach’s sow, and the other good things which the Highlanders

had taken from her. The gnawing demon of hunger that possessed him, inserted his fell

fangs more furiously into his stomach, from very association with the scene. What

would he not have now given for the smallest morsel of that goodly beast, the long

and ample side of which arose upon his mind’s eyes, as he had beheld her carcase hanging

from the bough of a tree, previous to the rapid subdivision which it underwent. [119]Alas! the very thought of it was now an unreal mockery. Yet he could not help looking

anxiously around, though in vain, among the extinguished remains of the fires of the

bivouacs; and he figured to himself the joy and comfort and refreshment he would have

experienced, if his eyes could have lighted even on a half-broiled fragment of one

of the pettitoes, which he might have picked at as he fled. John’s eyes were so intently

turned to the ground, that he saw not the unfortunate Mr. Dallas, who still dangled

from the bough of the fir tree above him.

Whilst John was poking about in this manner, earnestly turning over the ashes, and

looking amongst them as if he had been in search of a pin, he suddenly heard the tramp

of horses at some little distance. The sound was evidently coming towards him; and

he could distinguish men’s voices. He cast his eyes eagerly around him, to discover

some ready place of concealment; and now, for the first time, he caught sight of the

wasted figure of Mr. Dallas, swinging at some distance above him, with the dull [120]glassy eyeballs apparently fixed upon him. His heart sank within him; for the corpse

of the wretched man seemed to typify his own immediate fate. He was paralyzed for

a moment. But the sound drew nearer; and, spying a holly-tree with a reasonably tall

stem, and a very thick and bushy head, which happened to grow most fortunately near

him, he ran towards it, reached up his hands, seized hold of its lower branches, and,

weak though he was, the energy of self-preservation enabled him very quickly to coil

himself up amongst its dense foliage, where he sat as still as death, and scarcely

allowing himself to breathe. The holly-tree stood by the side of a horse-track that

led through the wood, and which crossed the small open space where most of the fires

of Captain M’Taggart’s bivouac had been kindled. Two troopers came riding leisurely

up through the wood along it, their horses considerably jaded by the work of the day.

“Ha!” said one of them to the other, reining up his steed as he spoke, just on entering

the open space,—“What have we here, Jack?”

[121]

“I should not wonder now if ’em ’ere should be the remains of the fires of some of

them rebel rascals,” said Jack, with wonderful acuteness. “Them is a proper set of

waggabones, to be sure. How we did lick the rascals! Didn’t we, Bob?”

“To be sure we did, Jack,” replied Bob.

“But you and I aint made much on it, arter all. I wish the captain at the devil—so

I do—for sendin’ us a unting arter that officer he was a wanting to ketch.”

“Aye,” said Jack; “so do I, from the bottom of my soul. But if we had ketcht him,

I think we should ’a gained a prize, seeing that he wur walued at twenty golden pieces

by his Highness the Duke. Whoy, who the plague could he be? Not the chap they calls

Prince Charles Stuart himself surelye? I should think that his carcase would fetch

a deal more money.”

“A deal more money indeed!” said Bob.

“Lord bless thee, I would not sell my share of him for an underd. But why may we not

ketch him yet, Jack? Look sharp; do—and [122]see if you can spy ere an oak in this wood, with a head so royal as to hide this Prince

Charles Stuart in it, as that ’ere one did King Charley the Second arter the great

battle of Worcester. Zounds! what a fortin you and I should make, an’ we could only

ketch him!”

“Pooh!” replied Jack, moving so close to the little holly, that his head and that

of John Smith were within two yards of each other—“Pooh man! there beant no oaks bigger

than this here holly, in all this blasted, cold, and wretched country.” And, at the

same time, he gave its bushy head a thwack with the flat of his sword that set every

leaf of it in motion, and John’s heart, body, muscles, and nerves, shaking in sympathy

with them.

“Beg your pardon,” said Bob. “I was in a great big wood yesterday—that same, I mean,

that spreads abroad all over the country, above that ’ere ould castle wot they calls

Cawdor Castle. And sitch oak trees as I seed there! My heyes, some on ’em had heads

as would cover half a troop! But, hark ye, Jack! Is [123]there no tree, think ye, fit to have a man in’t but an oak? Dost not think that a

good stout fir-tree now might support a man?”

“Oh,” replied Jack, “surelye, surelye. This here holly, for instance, might hide a

man in its head;”—and, as he said so, he gave the holly another thwack, that, for

a few moments, banished every drop of blood from the heart of John Smith. “But your

oak is your only tree for concealing your King or your Prince; for, as the old rhyme

has it,

‘The royal oak is not a joke.’

As for your firs, they may be well enough for affording a refuge to your men of smaller

mark.”

“Then you don’t think that ’ere feller, wot hangs from yonder fir tree, can be a King

or a Prince, do you, Jack?” demanded Bob, laughing heartily at his own joke.

“My heyes!” exclaimed Jack, rubbing his optics, and looking earnestly for some time

at the corpse of Mr. Dallas; “sure I cannot be mistaken? As I’m a soldier, that ’ere

is the very face, figure, clothes, and, above all, short [124]leg and queer shoe, of the identical feller wot sould me an ould watch, wot was of

no use, because you know it never went, and therefore it stands to reason that it

could only tell the hour twice in the twenty-four. I say surelye, surelye, that ’ere

is the very feller as sould me this here ould useless watch, for a bran new great

goer. Well, if it be’ant some satisfaction to see the feller hanging there, my name

aint Jack Blunt!”

“Them rascally rebels has robbed and murdered the poor wretch,” said Bob.

“Well,” replied Jack, “I am a right soft arted Christine; and therefore most surelye

do I forgive ’em for that same hact, if they’d never ha’ done no worse. But come Bob,

my boy; an’ we would be ketching kings or princes, I doubt we mun be stirrin’.”

“Aye, aye, that’s true—let’s be joggin’,” replied Bob.

You may believe, gentlemen, that it was with no small satisfaction that John Smith

beheld them apply their spurs to the sides of their weary animals. He listened to

their departing [125]footsteps until they were beyond the reach of his hearing; and then, conscious as

he felt himself, that he was in much too weak a state to have maintained an unequal

combat against two fresh and vigorous men, with the most distant chance of success,

he put up a fervent ejaculation of thankfulness for their departure, and his own safety.

He was in the act of preparing himself to drop from the tree, that he might continue

his flight, and was just putting down his legs from amid the thick foliage, when he

met with a new alarm, that compelled him to draw them up again with great expedition.

Some one on foot now came singing along up the path, and John had hardly more than

time to conceal himself again, when he beheld the person enter upon the open space,

near the holly tree where he was perched. And a very remarkable and striking personage

he was. He wore an old, soiled, torn, and tarnished regimental coat, which, though

now divested of every shred of the lace that had once adorned it, seemed to have once

belonged to an English officer; and this was put on over a tattered [126]Highland kilt, from beneath which his raw-boned limbs and long horny feet appeared

uncased by any covering. A dirty canvas shirt was all that showed itself where a waistcoat should have been, and that was

all loose at the collar, fully exhibiting a thin, long, scraggy neck, that supported

a head of extraordinary dimensions, and of the strangest malconformation, having a

countenance, in which the appearance of the goggle eyes alone, would have been enough

to have satisfied the most transient observer of the insanity of the individual to

whom they belonged. An old worn-out drummer’s cap completed his costume. He came dancing

along, with a large piece of cheese held up before him with both hands, and he went

on, singing, hoarsely and vehemently,—

“Troll de roll loll—troll de loll lay;

If I could catch a reybell, I would him flay—

Troll de roll lay—troll de roll lum—

And out of his skin I wud make a big drum.

Ho! ho; ho; that wud be foine. But stay; I mun halt here, and sit doon, and munch

up mye cheese that I took so cleverly from that [127]ould woman.—Ho! ho! ho! ho!—How nice it is to follow the sodgers! Take what we like—take

what we like!—Ho! ho!—This is livin’ like a man! They ca’ed me daft Jock in the streets

o’ Perth; but our sarjeant says as hoo that I’m to be made a captain noo.—Ho! ho!—A

captain! and to have a lang swurd by my side!—Ho! ho! ho!—I’ll be grand, very grand—and

I’ll fecht, and cut off the heads o’ the reybel loons!—Ho! ho! ho!

Troll de roll loll—troll de roll lay—

If I could catch a reybell I wud him——”

“Hoch!”—roared out John Smith, his patience being now quite exhausted, by the thought

that his chance of escaping with life was thus to be rendered doubly precarious, by

the provoking delay of this idiot.—“Hoch!” roared he again, in a yet more tremendous

voice, whilst at the same time he thrust his head—and nothing but his turf-covered

head—with his bloody countenance, partially streaked with the tiny streams of the

inky liquid that had oozed from the peat, and run down here and there [128]over his face;—this horrible head, I say, John thrust forth from the foliage, and

glared fearfully at the appalled songster, who stopped dead in the midst of his stave.

“Ah—a-ach—ha—a-ah—ha!” cried the poor idiot, in a prolonged scream of terror that

echoed through the wood, and off he flew, and was out of sight in a moment.

John Smith lost not another instant of time. Dropping down from the tree, he hastily

picked up a small fragment of the cheese which the idiot had let fall in his terror

and confusion, and this he devoured with inconceivable rapacity. But although this

refreshed him a little, it stirred up his hunger to a most agonizing degree, so that

if he had had no other cause for running, he would have run from the very internal

torment he was enduring. Dashing down through the thickest of the brakes of the wood,

so as to avoid observation as much as possible, he at last traversed the whole extent

of it in a north-easterly direction, and gained the low open country beyond it, whence

he urged on his way, until he fell into that very line of road, in the [129]parish of Petty, which he had so lately marched over in an opposite direction, and

under circumstances so different, with Captain M’Taggart and his company, on the afternoon

of the 14th, just two days before.

Remembering the whole particulars of that march, and the cheers and the benedictions

with which they had been every where greeted, John Smith flattered himself that he

had now got into a country of friends, and that he had only to show himself at any

of their doors, wounded, weary, an’ hungered and athirst, as he was, to ensure the

most charitable, compassionate, and hospitable reception. But, in so calculating,

John was ignorant of the versatility and worthlessness of popular applause. He forgot

that when he was passing to Culloden, with the bold Captain M’Taggart and his company,

they had been looked upon as heroes marching to conquest; whilst he was now to be

viewed as a wretched runaway from a lost field. But he still more forgot, that the

same bloody, haggard countenance, and horrible head-gear, which had been already so

great a protection to him by terrifying [130]his enemies, could not have much chance of favourably recommending him to his friends.

John stumped on along the road, therefore, with comparative cheerfulness, arising

from the prospect which he now had of speedy relief. At some little distance before

him, he observed a nice, trig-looking country girl, trudging away barefoot, in the

same direction he was travelling. He hurried on to overtake her, in order to learn

from her where he was most likely to have his raging hunger relieved. The girl heard

his footstep coming up behind her, whilst she was yet some twenty paces a-head of

him;—she turned suddenly round to see who the person was that was about to join her,

and beholding the terrible spectre-looking figure which John presented, she uttered

a piercing shriek, and darted off along the highway, with a speed that nothing but

intense dread could have produced. Altogether forgetful of the probable cause of her

alarm, John imagined that it must proceed from fear of the Duke of Cumberland’s men,

and, with this idea in his head, he ran after her as fast as his weak state of body

would allow him, [131]earnestly vociferating to her to stop. But the more he ran, and the more he shouted,

just so much the more ran and screamed the terrified young woman. Another girl was

seated, with a boy, on the grassy slope of a broomy hillock, immediately over the

road, tending three cows and a few sheep. Seeing the first girl running in the way

she was doing, they hurried to the road side to enquire the cause of her alarm, but

ere they had time to ask, or she to answer, she shot past them, and the hideous figure

of John Smith appeared. Horror-struck, and so bewildered that they hardly knew what

they were doing, both girl and boy leaped into the road, and fled along it. A little

farther on, two labourers were engaged digging a ditch, in a mossy hollow below the

road. Curiosity to know what was the cause of all this shrieking and running, induced

these men to hasten up to the road-side. But ere they had half reached it, they beheld

John coming, and turning with sudden dismay, they scampered off across the fields,

never stopping to draw breath till they reached their own homes. John [132]minded them not,—but fancying that he was gaining on the three fugitives before him,

and perceiving a small hamlet of cottages a little way on, he redoubled his exertions.

Some dozen of persons, men, women, and children, were assembled about a well, at what

we in Scotland would call the town-end. They were talking earnestly over the many,

and most contradictory rumours, that had reached them of the events of that day’s

battle, their rustic and unwarlike souls having been so sunk, with the trepidation

occasioned by the distant sound of the heavy cannonade, that they as yet hardly dared

to speak but in whispers. Suddenly the shrieking of the three young persons came upon

their ears. They pricked them up in alarm, and turned every eye along the road. The

shrieking increased, and the two girls and the boy appeared, with the formidable figure

of John Smith in pursuit of them.

“The Duke’s men! the Duke’s men! with the devil at their head!” cried the wise man

of the hamlet in Gaelic. “Run! or we’re all dead and murdered!”

[133]

In an instant every human head of them had disappeared, each having burrowed under

its own proper earthen hovel, with as much expedition as would be displayed by the

rabbits of a warren, when scared by a Highland terrier. So instantaneously, and so

securely, was every little door fastened, that it was with some difficulty that the

three fugitives found places of shelter, and that too, not until their shrieks had

been multiplied ten-fold. When John Smith came up, panting and blowing like a stranded

porpus, all was snug, and the little hamlet so silent, that if he had not caught a

glimpse of the people alive, he might have supposed that they were all dead.

John knocked at the first door he came to.—Not a sound was returned but the angry

barking of a cur. He tried the next—and the next—and the next—all with like success;—at

last he knocked at one, whence came a low, tremulous voice, more of ejaculation than

intended for the ear of any one without, and speaking in Gaelic.

“Lord be about us!—Defend us from Satan, and from all his evil spirits and works!”

“Give me a morsel of bread, and a cup of [134]water, for mercy’s sake!” said John, poking his head close against a small pane of

dirty glass in the mud wall, that served for a window.

“Avoid thee, evil spirit!” said the same voice.—“Avoid thee, Satan!—O deliver us from

Satan!—Deliver us from the Prince of Darkness and all his wicked angels!”

“Have mercy upon me, and give me but a bit of bread, and a drop of water, for the

sake of Christ your Saviour!” cried John earnestly again.

“Avoid, I say, blasphemer!” replied the voice, with more energy than before. “Name

not vainly the name of my Saviour, enemy as thou art to him and his. Begone, and tempt

us not!”

John Smith was preparing to answer and to explain, and to defend himself from these

absurd and unjust imputations against him, when he heard the sound of a bolt drawn

in the hovel immediately behind him. Full of hope that some good and charitable Christian

within, melted by his pitiful petitions, had come to the resolution of opening his

door to relieve him, he turned hastily round. But what was his mortification, [135]when, instead of seeing the door opened, he beheld the small wooden shutter of an

unglazed hole in the wall, slowly and silently pushed outwards on its hinges, until

it fell aside, and then the muzzle of a rusty fowling-piece was gradually projected,

levelled, and pointed at him. John waited not to allow him who held it to perfect

his aim. He sprang instantly aside towards the wall, and fortunately, the tardy performance

of the old and ill constructed lock enabled him to do so, just in time to clear the

way for the shower of swan-shot which the gun discharged in a diagonal line across

the way. Luckily for John, he had thus no opportunity of judging of the weight of

the charge in his own person, but he was made sufficiently aware that it was quite

potent enough, by its effects on an unfortunate sheep-dog, that happened to be at

that moment lying peaceably gnawing a bone on the top of a dunghill, some fifty yards

down the road, on the opposite side of the way to that where the hovel stood from

which the shot had been fired. The poor animal sprang up, and gave a loud and sharp

yelp, when he received the [136]shot, and then followed a long and dismal howl, after which he rolled over on his

back and died. After such a hint as this, John staid not to make farther experiments

on the hospitality of the little place, but, getting out at the farther end of its

street with all manner of expedition, he slowly proceeded on his way, weary, faint,

and heart-sunken.

Just as sunset was approaching, he came to the door of a small single cottage, hard

by the way-side. There he knocked gently, without saying a word.

“Who is there?” asked a soft woman’s voice in Gaelic, from within.

“A poor man like to die with hunger and thirst,” replied John in the same language.

“For the love of God give me a piece of bread, and a drink of water.”

“You shant want that,” said the good Samaritan woman within, who promptly came to

undo the door.

“Heaven reward you!” said John fervently, as she was fumbling with the key in the

key-hole, and with an astonishing rapidity of movement [137]in his ideas, he felt, by anticipation, as if he was already devouring the food he

had asked for.

“Preserve us, what’s that?” cried the woman, the moment the half-opened door had enabled

her to catch a glimpse of his fearful head and bloody features.

The door was shut and locked in an instant; and whether it was that the poor young

lonely widow, for such she was, had fainted or not, or whether she had felt so frightened

for herself and her young child, that she dared not to speak, all John’s farther attempts

to procure an answer from her were fruitless. It was probably from the cruel and unexpected

disappointment that he here had met with, just at the time when his hopes of relief

had been highest, that his faintness came more overpoweringly upon him. He tottered

away from the widow’s door, with his head swimming strangely round, and he had not

proceeded above two or three dozen of steps, when he sank down on a green bank by

the side of the road, where he lay almost unconscious as to what had befallen him.

He had not lain long there, when the tender [138]hearted widow, who had reconnoitred him well through a single pane of glass in the

gable end of her house, began to have her fears overcome by her compassion. Seeing

that he was now at some distance from her dwelling, she ventured again to open her

door, and perceiving that he did not stir, she retired for a minute, and then reappeared

with a bottle of milk and two barley cakes, with which she crept timorously, and therefore

slowly and cautiously, along the road. Her step became slower and slower, as, with

fear and trembling, she drew near to John. At last, when within three or four yards

of him, she halted, and, looking back, as if to measure the distance that divided

her from her own door, she turned towards him, and ventured to address him.

“Here, poor man,” said she, setting down the cakes and the bottle of milk on the bank.

“Here is some refreshment for you.”

John Smith raised his eyes languidly as her words reached him, and spying the food

she had brought him, he started up and proceeded to seize upon it with an energy which

no one could have believed was yet left in him; and, as the benevolent [139]widow was flying back with a beating heart to her cottage, she heard his thanks and

benedictions coming thickly and loudly after her. John devoured the barley cakes,

and drank the milk, and felt wonderfully refreshed, and then, placing the bottle on

the bank in view of the cottage, he knelt down and offered up his thanks to God for

his mercy, and prayed for blessings on the head of her who had relieved him. He then

arose, and having waved his hand two or three times towards the cottage in token of

his gratitude, he proceeded with some degree of spirit on his journey. I may here

remark, gentlemen, that however those worthies who denied John admittance to their

houses may have passed the night, I may venture to pronounce, and that with some probability

of truth too, that the sleep of that virtuous young widow, with her innocent child

in her arms, was as sweet and refreshing as the purity and balminess of her previous

reflections could make it.

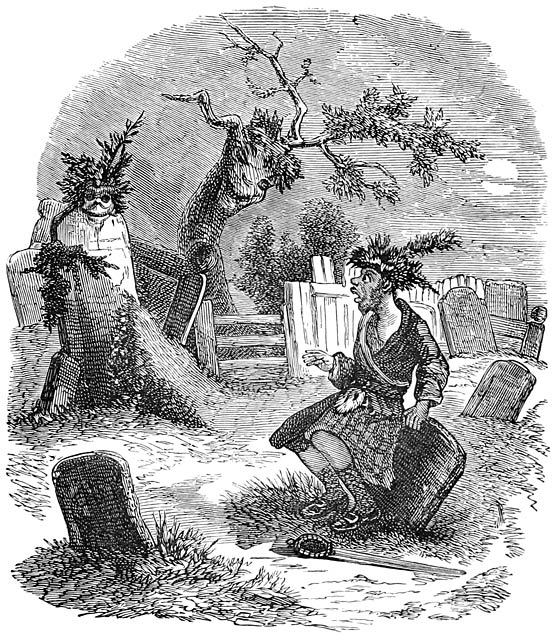

John Smith had not gone far on his way till the sun went down; but, as the moon was

up, and he knew his road sufficiently well, he continued [140]to trudge on without fear, until he approached the old walls of an ancient church,

the burying yard of which had an ugly reputation for being haunted, and then he began

to walk with somewhat more circumspection. As he drew nearer to it, he halted under

the shadow of a bank, and stood for a time somewhat aghast, for, in the open part

of the grave-yard, between the church and the high-road, he beheld three figures standing

in the moonlight which then prevailed. At first John quaked with fear, lest they should

prove to be some of the uncanny spirits which were said to frequent the place. But

he soon became reassured, by observing enough of them and of their motions to convince

him that they were men of flesh and blood, yea, and Highlanders too, like himself.

As John Smith had no fear of mortal man, he would have at once advanced. But there

was something so suspicious in the manner in which the three fellows hung over the

wall, as if they were watching the public road, that he became at once convinced that

they were lying in wait for a prey; and although he had nothing [141]to lose, he did not feel quite assured as to the manner in which they might be disposed

to accost him; and in his present weak state, he felt prudence to be the better part

of valour. Availing himself of the concealment of the bank, therefore, until he had

entered a small opening in the churchyard wall, he crept quietly across a dark part

of the churchyard itself, by which means he got into the deep shadow that fell with

great breadth all along the church wall, between the moon and the three figures who

were watching the road, and who consequently had their backs to the old building.

Having succeeded in accomplishing this, John was stealing slowly and silently along

the wall, with the hope of passing by them, altogether unnoticed, when, as ill luck

would have it, one of them chanced to turn round, so as dimly to descry his figure.

“What the devil is that gliding along yonder?” cried the man, in Gaelic, and in a

voice that betrayed considerable fear.

“Halt you there!” cried another, who was somewhat bolder. “Halt, I say, and give an

account of yourself.”

[142]

John saw that there was now no mode of escaping the danger but by boldly bearding

it. He halted therefore, but still keeping deep within the shade, he drew out his

claymore, and placed his back to the church wall to prepare for defence.

“Ha! steel!” cried the third fellow; “I heard it clash on the stones of the wall,

and I saw it bring a flash of fire out of them too. Come, come, goodman, whoever you

are—come out here, and give us your claymore.”

“He that will have it, must come and take it by the point,” said John, in Gaelic,

and in a stern, hoarse, hollow voice; “and he had better have iron gloves on, or he

will find it too hot for his palms.”

“What the devil does he mean?” said the first.

“We’ll detain you as a runaway rebel,” said the third.

“The boldest of men could not detain me,” replied John, now recognising the last speaker,

by the moonlight on his face, as well as by his voice. “But for a base traitor like

you, Neil MacCallum, better were it for you to be lying [143]dead, like your brave brother, among the slain on Drummosie Moor, than to encounter

me here in this churchyard, at such an hour as this!”

“In the name of wonder, how knows he my name?” exclaimed MacCallum in a voice that

quavered considerably.

“Oh, Neil! Neil!” cried the first speaker, in great dismay, “it is no man! it is something