The Project Gutenberg EBook of Shackleton's Last Voyage, by Frank Wild

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll

have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using

this ebook.

Title: Shackleton's Last Voyage

The Story of the Quest

Author: Frank Wild

Release Date: February 27, 2019 [EBook #58973]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SHACKLETON'S LAST VOYAGE ***

Produced by Tim Lindell, Melissa McDaniel and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

Transcriber’s Note:

Inconsistent hyphenation and spelling in the original document have been preserved. Obvious typographical errors have been corrected.

There is a possible missing word on page 135 in the sentence: “One has to be economical these hard times.”

On page 291, “Groote Schur” should possibly be “Groote Schuur”.

SHACKLETON’S

LAST VOYAGE.

The Story of the Quest. By

Commander FRANK WILD, c.b.e.

From the Official Journal and Private

Diary kept by Dr. A. H. MACKLIN

With Frontispiece in Colour, numerous Maps

and over 100 Illustrations from Photographs

CASSELL AND COMPANY, LTD

London, New York, Toronto and Melbourne

1923

First Published May 1923.

Second Edition June 1923.

Reprinted November 1923

Printed in Great Britain

To

THE BOSS

“Yonder the far horizon lies,

And there by night and day

The old ships draw to port again,

The young ships sail away.

And go I must and come I may,

And if men ask you why,

You may lay the blame on the stars and the sun

And the white road and the sky.”

Gerald Gould

Sir Ernest Shackleton died suddenly; so suddenly that he said no word at all with regard to the future of the expedition. But I know that had he foreseen his death and been able to communicate to me his wishes, they would have been summed up in the two words, “Carry on!”

Perhaps the most difficult part of my task has been the recording of the work of the expedition. It has been to me a very sad duty, and one which I would gladly have avoided had it been possible. The demand, however, for the complete story of Sir Ernest Shackleton’s last expedition has been so widespread and insistent that I could no longer withhold it.

In the subsequent pages of this book the reader will find recorded the story of the voyage of the Quest, the tight little ship that carried us through over twenty thousand miles of stormy ocean and brought us safely back.

I make no claim to literary style, but have endeavoured to set forth a plain and simple narrative.

The writings of explorers vary, but in my opinion they have all one common fault, which is, that they have attempted to combine in one volume the scientific results with the more popular story of the expedition.

This book is for the public. I have sought to viii eliminate the mass of scientific details with which my journal is filled, to avoid technical terms, and to retain only that which can be easily understood by all.

Of the parts of the narrative that deal with Sir Ernest Shackleton I have passed over very shortly. Pens far more able than mine, notably those of Mr. Harold Begbie and Dr. Hugh Robert Mill, have written of his life and character.

Though I was his companion on every one of his expeditions, I know little of his life at home. It is a curious thing that men thrown so closely together as those engaged in Polar work should never seek to know anything of each other’s “inside” affairs. But to the “Explorer” Shackleton I was joined by ties so strongly welded through the many years of common hardship and struggle that to write of him at all is extremely difficult. Nothing I could set down can convey what I feel, and I have a horror of false and wordy sentiment. I trust, therefore, that those readers who may think that I have dealt too lightly with the parts of the story which more intimately concern him will sympathize and respect my feelings in the matter.

I must take this opportunity of acknowledging my deep feeling of gratitude to Mr. John Quiller Rowett. What the expedition owes to him no one, not even its individual members, can ever realize. There have been many supporters of enterprises of this nature, but usually they have sought from it some commercial gain. Mr. Rowett’s support was due solely to his keen interest in scientific research, which he had previously instituted ix and encouraged in other fields. He bore practically the whole financial burden, and this expedition is almost unique in that it was clear of debt at the time of its return.

But, in addition to this, I owe him much for his kindly encouragement, his clear, sound judgment, and his unfailing assistance whenever I have sought it. Mrs. Rowett has given me invaluable assistance throughout the preparation of the book and has corrected the proofs. For her kindly hospitality I owe more than I can say, for to myself and others of the expedition her house has ever been open, and we have received always the most kindly welcome. In this connexion I could say a great deal, but it would be inadequate to convey what I feel.

The expedition owes also a debt of gratitude to Sir Frederick Becker, for his encouraging assistance was rendered early in its inception.

To the many public-spirited firms who came forward with offers of assistance to what was considered a national enterprise I must make my acknowledgments. It is regrettable that many of the smaller suppliers of the expedition seized the chance of a cheap advertisement at the time of our departure, but a number of the more reputable firms made no stipulation of any sort, but presented us with goods as a free gift. I can assure them that I do not lightly regard their share in helping on the work, for we were thus enabled to carry in our food stores only the best of products, Sir Ernest Shackleton rigidly eliminating all goods which he felt unable to trust. x

To Mr. James A. Cook I owe much for the hard work he has done at all times and for the help which he rendered whilst the expedition was away from England.

To my many other friends who have at one time and another been of assistance I tender my grateful acknowledgments, knowing full well that they will realize how impossible it is for me to thank them all by name.

I must thank Dr. Macklin for the care he took in keeping the official diary of the expedition. This and his own private journal, from which I have freely quoted, have both been invaluable to me.

To “The Boys,” those who stood by me and gave me their loyal service throughout an arduous and trying period, I say nothing—for they know how I feel.

Frank Wild.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | ||

| 1. | Inception | 1 | |

| 2. | London to Rio de Janeiro | 16 | |

| 3. | Rio to South Georgia | 44 | |

| 4. | Death of Sir Ernest Shackleton | 64 | |

| 5. | Preparations in South Georgia | 71 | |

| 6. | Into the South | 80 | |

| 7. | The Ice | 122 | |

| 8. | Elephant Island | 155 | |

| 9. | South Georgia (Second Visit) | 173 | |

| 10. | The Tristan da Cunha Group | 199 | |

| 11. | Tristan da Cunha | By Dr. Macklin | 219 |

| 12. | Tristan da Cunha (continued) | By Dr. Macklin | 243 |

| 13. | Diego Alvarez or Gough Island | 265 | |

| 14. | Cape Town | 287 | |

| 15. | St. Helena—Ascension Island—St. Vincent | 294 | |

| 16. | Home | 310 | |

| Appendices | |||

| I.—Geological Observations | 314 | ||

| II.—Natural History | 328 | ||

| III.—Meteorology | 340 | ||

| IV.—Hydrographic Work | 343 | ||

| V.—Medical | 352 | ||

| List of Personnel | 366 | ||

| Index | 367 | ||

| The Cairn | Colour Frontispiece | |

| Plate | FACING PAGE | |

| 1. | Sir Ernest Shackleton in Polar Clothing | 4 |

| 2. | Mr. John Quiller Rowett | 5 |

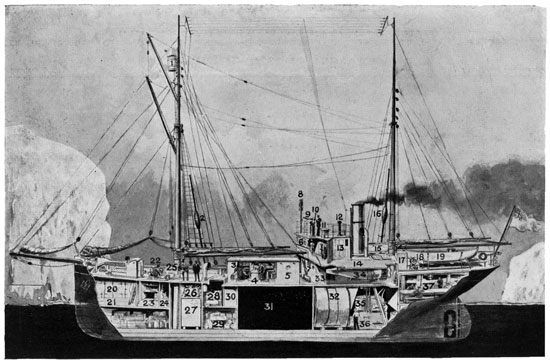

| 3. | A Diagrammatic View of the Quest | 6 |

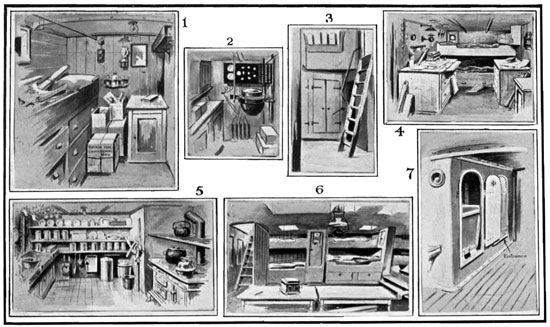

| 4. | Sectional Views of the Quest | 7 |

| 5. | The Sperry Gyroscopic Compass | 10 |

| 6. | The Enclosed Bridge of the Quest | 11 |

| 7. | The Quest at Hay’s Wharf | 12 |

| 8. | Kerr (Chief Engineer) Examining the Lucas Deep-sea Sounding Machine | 13 |

| 9. | The Wireless Operating Room—The Ward Room of the Quest | 20 |

| 10. | The Quest Passing the Tower of London on her way to the Sea—The Schermuly Portable Rocket Apparatus | 21 |

| 11. | The Quest in the North-east Trades | 28 |

| 12. | The Tow Net in Use | 29 |

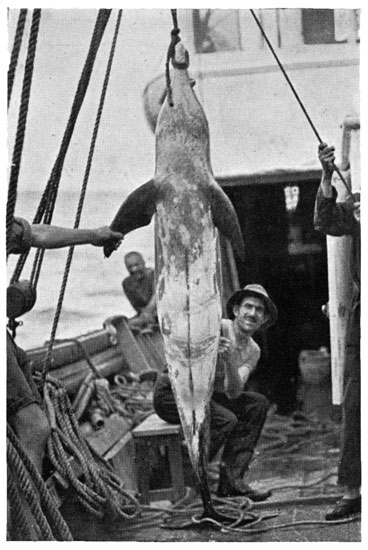

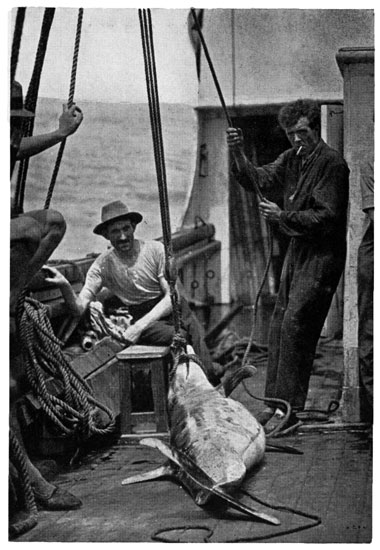

| 13. | A Porpoise which was Harpooned from the Bowsprit | 32 |

| 14. | Query—The Boss Gives Query a Bath | 33 |

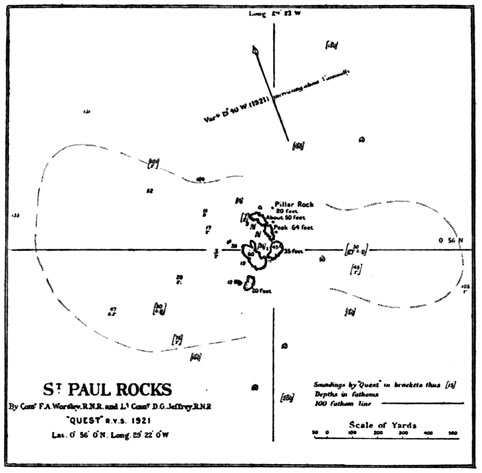

| 15. | Landing the Shore Party at St. Paul’s Rocks | 48 |

| 16. | The White-capped Noddy (Anous stolidus) on St. Paul’s Rocks—The Booby (Sula leucogastra) | 49 |

| 17. | Commander Worsley Superintending Work in the Rigging at Rio de Janeiro | 50 |

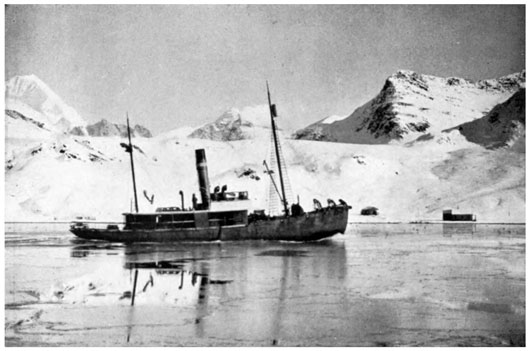

| 18. | The Quest in Gritviken Harbour | 51 |

| 19. | The Whaling Station at Gritviken | 62 |

| 20. | Sunset on the Slopes of South Georgia | 63 |

| 21. | The Resting Place of a Great Explorer | 64 |

| 22. | The Picturesque Setting of Prince Olaf Station | 65 |

| 23. | Prince Olaf Whaling Station | 68 |

| 24. | A Steam Whaler with Two Whales brought in for Flensing—Huge Blue Whales at South Georgia | 69 |

| 25. | The “Plan” at Gritviken, with a Whale in Process of Being Flensed | 76xiv |

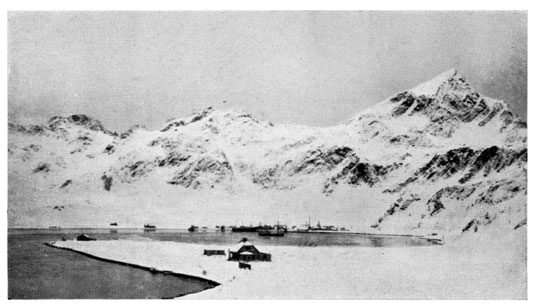

| 26. | Leith Harbour, South Georgia | 77 |

| 27. | Chart of Larsen Harbour—The Entrance to Larsen Harbour | 80 |

| 28. | An Expedition in Search of Fresh Food—Marr, McIlroy, Commander Wild, Macklin | 81 |

| 29. | Commander Wild | 82 |

| 30. | A Small Berg—A Curious “Toothed” Berg | 83 |

| 31. | A Lovely Evening in the Sub-Antarctic | 86 |

| 32. | Too Many Cooks—Our First Deep-sea Sounding | 87 |

| 33. | The Western End of Zavodovski Island, showing Grounded Icebergs | 90 |

| 34. | Sentinel of the Antarctic | 91 |

| 35. | A Typical Scene at the Pack Edge | 94 |

| 36. | Killers Rising to “Blow”—The Quest Pushing Through Thin Ice | 95 |

| 37. | Loose Open Pack—Loose Pack Ice, with the Sea Rapidly Freezing Over | 96 |

| 38. | The Midnight Sun | 97 |

| 39. | The Loneliness of the Pack | 100 |

| 40. | An Unpleasant but Necessary Duty—Taking Crab-eater Seals for Food | 101 |

| 41. | Commander Wild at the Masthead | 108 |

| 42. | Pushing South Through Heavy Pack—The Quest Ploughing Through Heavy Ice Pack | 109 |

| 43. | The Quest at her Farthest South—Jeffrey and Douglas taking Observations for Magnetic Dip | 112 |

| 44. | Heavy Pressed-up Pack Ice, the Quest in the Distance—Commander Wild and Worsley Examining a Newly Formed “Lead” in the Pack Ice | 113 |

| 45. | The Quest Pushing North Through Rapidly Freezing Ice | 114 |

| 46. | “Watering” Ship with Floe Ice | 115 |

| 47. | Emperor Penguins on the Floe: A Still Evening in the Pack | 118 |

| 48. | Frozen Spray | 119 |

| 49. | Commander Wild’s Watch: McIlroy, Carr, Wild, Macklin—The “Black” Watch: Ross, Argles, Young, Kerr, Smith | 122 |

| 50. | Worsley’s Watch: Douglas, Wilkins, Watts, Worsley—Jeffrey’s Watch: McLeod, Marr, Jeffrey, Dell | 123 |

| 51. | Chipping Frozen Spray from the Gunwales | 126 |

| 52. | The Quest Beset near Ross’s Appearance of Land | 127 |

| 53. | Rowett Island, off Cape Lookout, Elephant Island | 150xv |

| 54. | The Kent “Clear-View” Screen—Approaching Cape Lookout | 151 |

| 55. | Loading Sea-elephants’ Blubber, Elephant Island | 154 |

| 56. | Somnolent Content: a Sea-elephant on Elephant Island—Ringed Penguins and a Paddy Bird (Chionis alba) | 155 |

| 57. | Shackleton’s Last Anchorage—McLeod and Marr clearing up After a Blizzard | 160 |

| 58. | Sugar Top Mountain, Part of the Allardyce Range, South Georgia | 161 |

| 59. | A Glacier Face in South Georgia | 176 |

| 60. | A Rocky Outcrop in South Georgia | 177 |

| 61. | Distended Whale Carcasses in Prince Olaf Harbour | 178 |

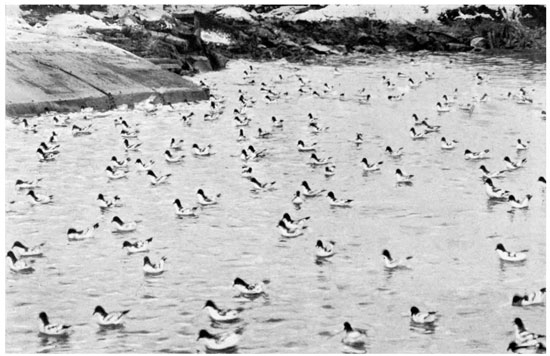

| 62. | Cape Pigeons (Daption capensis) at South Georgia | 179 |

| 63. | The Northern Coast of Drygalski Fiord—Cape Saunders | 182 |

| 64. | The New Type of Whaler—The Black-browed Albatross or Mollymauk | 183 |

| 65. | A Pair of Adult Wandering Albatross—A Young Albatross | 186 |

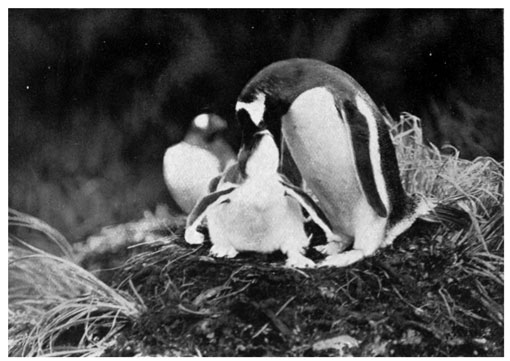

| 66. | Gentoo Penguin Feeding its Chick—The Chick after Feeding | 187 |

| 67. | On the Way to the Cairn—Looking Shorewards from the Cairn | 190 |

| 68. | Our Farewell to the Boss | 191 |

| 69. | The Settlement at Tristan da Cunha from the Sea—View of the Settlement from the East | 208 |

| 70. | Landing at Big Beach, Tristan da Cunha—A Tristan Bullock Cart | 209 |

| 71. | Nightingale Island—Inaccessible Island | 224 |

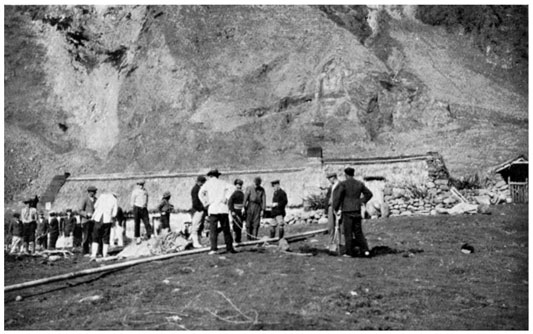

| 72. | Wireless Pole being erected, Tristan—Carr and Douglas with Two Tristan Guides, Henry Green and Glass | 225 |

| 73. | John Glass and Family—The Mission House on Tristan da Cunha | 240 |

| 74. | The “Potato Patches” on Tristan da Cunha | 241 |

| 75. | Tristan Women Twisting Wool—The Tristan Method of Carding Wool | 256 |

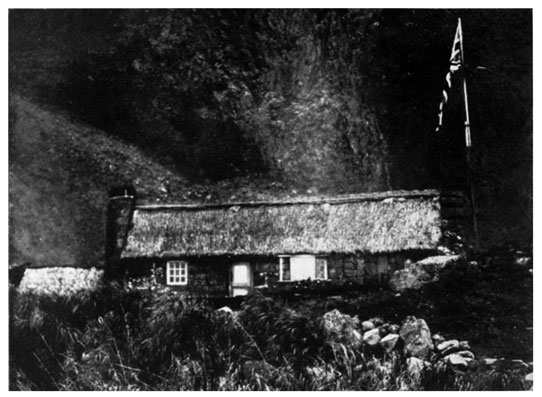

| 76. | Henry Green’s Cottage, Tristan da Cunha—The Oldest Inhabitant of Tristan da Cunha, Miss Betty Cotton | 257 |

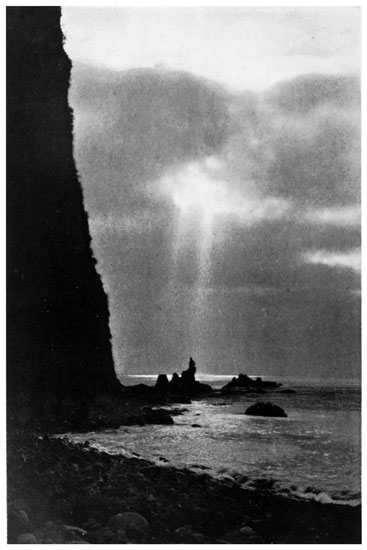

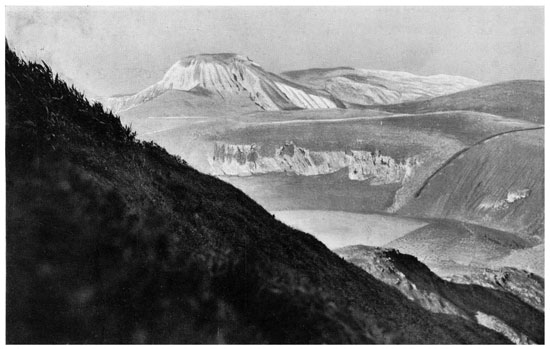

| 77. | View of Gough Island from the Glen Anchorage | 262 |

| 78. | The Apostle, an Acid Intrusive near the Summit of Gough Island—The Little Glen where the New Sophora was Discovered | 263xvi |

| 79. | On the Way to the Summit | 266 |

| 80. | The Glen Anchorage from the Higher Slopes | 267 |

| 81. | The Quest seen through the Archway Rock, Gough Island | 276 |

| 82. | Dell Rocks, at the North-eastern End of Glen Beach | 277 |

| 83. | Lot’s Wife Cove and Church Rocks, Gough Island | 284 |

| 84. | Lot’s Wife, Gough Island | 285 |

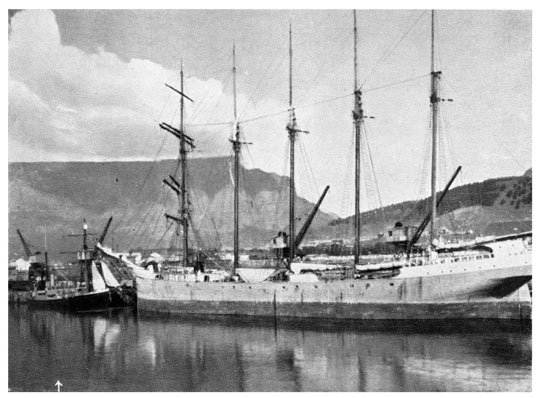

| 85. | The Quest Entering Table Bay—The Quest in Dock at Cape Town | 288 |

| 86. | The Summit of Ascension Island | 289 |

| 87. | The Abandoned Wireless Station on Ascension Island—Flowering Plants Growing in the Volcanic Ash at Ascension Island | 304 |

| 88. | Wideawake Plain, Ascension Island—A Wideawake | 305 |

| 89. | Weatherpost Hill, Ascension Island, Looking East | 308 |

| 90. | A View in San Miguel in the Azores | 309 |

| 91. | Booby with Chick—A Booby Chick | 316 |

| 92. | Types of Fish Caught in the Lagoon at St. Paul’s Rocks—White-capped Noddies at St. Paul’s Rocks | 317 |

| 93. | Gentoo Penguin with Two Chicks—Nesting Ground of the Mollymauk | 320 |

| 94. | Giant Petrel at Nest | 321 |

| 95. | The Surface of a Glacier, showing Numerous Crevasses | 336 |

| 96. | Sea-elephants in Tussock Grass | 337 |

| 97. | The Island Tree (Phylica nitida)—Sea-elephants among the Rocks | 340 |

| 98. | Commander Worsley taking Observations of the Sun by Sextant—Hussey (Taking Sea Temperatures), Commander Wild and McIlroy | 341 |

| 99. | Setting up Kites for the Taking of Meteorological Observations | 348 |

| 100. | An Apparatus for Bringing Up Specimens of the Sea Bottom | 349 |

Shackleton’s Last Voyage

After the finish of the Great War, which had employed every able-bodied man in the country in one way or another, Sir Ernest Shackleton returned to London and wrote his famous epic “South,” the story of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. Before it was finished he had again felt the call of the ice, and concluded his book with the following sentence: “Though some have gone, there are enough to rally round and form a nucleus for the next expedition, when troublous times are over, and scientific exploration can once more be legitimately undertaken.”

For many years he had had an inclination to take an expedition into the Arctic and compare the two ice zones. He felt, too, a keen desire to pit himself against the American and Norwegian explorers who of recent years had held the foremost position in Arctic exploration, to win for the British flag a further renown, and to add to the sum of British achievements in the frozen North.

There is still, in spite of the long and unremitting siege which has gradually tinted the uncoloured portions of the map and brought within our ken section after section of the unexplored areas, a large blank space 2 comprising what is known as the Beaufort Sea, approximately in the centre of which is the point called by Stefansson the “centre of the zone of inaccessibility.” It was the exploration of this area that Sir Ernest made his aim. In addition he felt a strong desire to clear up the mystery of the North Pole, and for ever settle the Peary-Cook controversy, which did so much to alienate public sympathy from Polar enterprise.

It is characteristic of him that before proceeding with any part of the organization he wrote first to Mr. Stefansson, the Canadian explorer, to ask if the new expedition would interfere with any plan of his. He received in reply a letter saying that not only did it not interfere in any way, but that he (Stefansson) would be glad to afford any help that lay in his power and put at his disposal any information which might prove valuable.

Sir Ernest’s plans were the result of several years of hard work with careful reference to the records of previous explorers, and his organization was remarkable for its completeness and detail.

The proposed expedition had an added interest in that the whole of his Polar experience was gained in the Antarctic. It met with instant recognition from the leading scientists and geographers of this country, who saw in it far-reaching and valuable results. The Council of the Royal Geographical Society sent a letter which showed their appreciation of the importance of the work, and expressed their approval of himself as commander and of the names he had submitted as those of men eminently qualified to make a strong personnel for the expedition.

Sir Ernest Shackleton was fortunate in securing the active co-operation in the working out of his plans of 3 Dr. H. R. Mill, the greatest living authority on Polar regions.

The scheme, however, was an ambitious one, and was likely to prove costly.

The period following the end of the war was perhaps not a suitable one in many ways to commence an undertaking of this nature, for Sir Ernest had the greatest difficulty in raising the necessary funds. In this country he received the support of Mr. John Quiller Rowett and Sir Frederick Becker.

Feeling that the work of exploration and the possible discovery of new lands in what may be called the Canadian sector of the Arctic was likely to be of interest to the Canadian Government, he visited Ottawa, where he was in close touch with many of the leading members of the Canadian House of Commons. He returned to this country well pleased with his visit, and stated that he had obtained the active co-operation of several prominent Canadians and received from the Canadian Government the promise of a grant of money.

He was now in a position to start work, and immediately threw himself into the preparation of the expedition. He got together a small nucleus of men well known to him, including some who had accompanied him on the Endurance expedition, designed and ordered a quantity of special stores and equipment, and bought a ship which cost as an initial outlay £11,000. Dr. Macklin was sent to Canada to buy and collect together at some suitable spot a hundred good sledge-dogs of the “Husky” type.

It would be impossible to convey an accurate idea of the closely detailed work which is involved in the preparation for a Polar expedition. Much of the equipment 4 is of a highly technical nature and requires to be specially manufactured. Everything must be carried and nothing must be forgotten, for once away the most trivial article cannot be obtained. Everything also must be of good quality and sound design; and each article, whatever it may be, must function properly when actually put into use.

At what was almost the last moment, whilst preparations were in full swing, the Canadian Government, being more or less committed to a policy of retrenchment, discovered that they were not in a position to advance funds for this purpose, and withdrew their support. This was a great blow, for it made impossible the continuance of the scheme.

In the meantime the bulk of the personnel had been collected, some of the men having come from far distant parts of the world to join in the adventure, abandoning their businesses to do so. Some of us, knowing of the scheme, had waited for two years, putting aside permanent employment so that we might be free to join when required; for such is the extraordinary attraction of Polar exploration to those who have once engaged in it, that they will give up much, often all they have, to pit themselves once more against the ice and gamble with their lives in this greatest of all games of chance. Yet if you were to ask what is the attraction or where the fascination of it lies, probably not one could give you an answer.

Sir Ernest Shackleton received the blow with outward equanimity, which was not shaken when, with the decision of the Canadian Government, the more timorous of his supporters also withdrew. Always seen at his best in adverse circumstances, he wasted no time in useless 5 complainings, but started even at this eleventh hour to remodel his plans.

Nevertheless, the situation was a very difficult one. He had committed himself to heavy expenditure, and what weighed not least with him at this time was his consideration for the men who had come to join the enterprise. At this critical point Mr. John Quiller Rowett came forward to bear an active part in the work, and took upon his shoulders practically the whole financial responsibility of the expedition. The importance of this action cannot be too much emphasized, for without it the carrying on of the work would have been impossible.

Mr. Rowett had a wide outlook which enabled him to take a keen interest in all scientific affairs. Previous to this he had helped to found the Rowett Institute for Agricultural Research at Aberdeen, and had prompted and given practical support to researches in medicine, chemistry and several other branches of science. His many interests included geographical discovery, and he saw clearly the important bearing which conditions in the Polar regions have upon the temperate zones. He saw also the possible economic value of the observations and data which would be collected.

His name must therefore rank amongst the great supporters of Polar exploration, such as the brothers Enderby, Sir George Newnes and Mr. A. C. Harmsworth (afterwards Lord Northcliffe).

Mr. Rowett’s generous action is the more remarkable in that he was fully aware in giving this support to the expedition that there was no prospect of financial return. What he did was done purely out of friendship to Shackleton and in the interests of science. The new 6 expedition was named the Shackleton-Rowett Expedition, and announcement of it was received by the public with the greatest interest.

As it was now too late to catch the Arctic open season, the northern expedition was cancelled, and Sir Ernest reverted to one of his old schemes for scientific research in the South, which again met with the approval of the chief scientific bodies.

This change of plans threw an enormous burden of work not only upon Sir Ernest, but also upon those of us who formed his staff at this period, for we had little time in which to complete the preparations. Dr. Macklin was recalled from Canada, for under the new scheme sledge-dogs were not required.

The programme did not aim at the attainment of the Pole or include any prolonged land journey, but made its main object the taking of observations and the collection of scientific data in Antarctic and sub-Antarctic areas.

The proposed route led to the following places: St. Paul’s Rocks on the Equator, South Trinidad Island, Tristan da Cunha, Inaccessible Island, Nightingale and Middle Islands, Diego Alvarez or Gough Island, and thence to Cape Town.

Cape Town was to be the base for operations in the ice, and a depot of stores for that part of the journey would be formed there. The route led eastward from there to Marion, Crozet and Heard Islands, and then into the ice, where the track to be followed was, of course, problematical, but would lead westwards, to emerge again at South Georgia.

By courtesy of Illustrated London News

A DIAGRAMMATIC VIEW OF THE QUEST

1. Crow’s Nest with Gyro-compass; 2. Mark Buoy; 3. Sperry Gyro-compass; 4, Hydrographic Room; 5. Sir Ernest Shackleton’s Quarters; 6. Clear View Screen; 7. Kipling’s “If”; 8. Semaphore; 9. Range Finder; 10. Standard Binnacle; 11. Meteorological Screen; 12. Gyro-compass; 13. Wireless Room; 14. Life-boat Deck; 15. One of two Life-boats; 16. Mark Buoy; 17. Water Tank; 18. Kelvin Sounding Machine; 19. Surf Boat; 20. Stowage for Stores and Specimens; 21. Sleeping Accommodation for Naturalist and Photographer; 22. Windlass; 23. Dark-room; 24. Chain-locker; 25. Lucas Sounding Machine; 26. Stores; 27. 15-ton Water Tank; 28 and 29. Stores; 30. High-power Wireless Room; 31. Coal Bunkers; 32. Boiler; 33. Galley; 34. Avro; 35. Main Engines; 36. Engine Room; 37. Ward Room.

By courtesy of Illustrated London News

SECTIONAL VIEWS OF THE QUEST

1. Sir Ernest Shackleton’s Quarters; 2. Sperry Gyro-compass Hydrographic Room; 3. Entrance to Dark Room; 4. The Hydrographic Room; 5. The Galley; 6. Ward Room; 7. Bath Room under the Bridge (Starboard side).

From South Georgia it led to Bouvet Island, and back to Cape Town to refit. From Cape Town, the 7 second time, the route included New Zealand, Raratonga, Tuanaki (the “Lost Island”), Dougherty Island, the Birdwood Bank, and home via the Atlantic.

The scientific work included the taking of meteorological observations, including air and sea temperatures, kite and balloon work, magnetic observations, hydrographical and oceanographical work, including an extensive series of soundings, and the mapping and careful charting of little-known islands. Search was to be made for lands marked on the map as “doubtful.” A collection of natural history specimens would be made, and a geological survey and examination carried out in all the places visited. Ice observations would be carried on in the South, and an attempt made to reach and map out new land in the Enderby Quadrant. Photography was made a special feature, and a large and expensive outfit of cameras, cinematograph machines and general photographic appliances acquired.

The Admiralty and the Air Ministry co-operated and materially assisted by lending much of the scientific apparatus. Lieut.-Commander R. T. Gould, of the Hydrographic Department, provided us with books and reports of previous explorers concerning the little-known parts of our route, and his information, gleaned from all sources and collected together for our use, proved of the greatest value.

It was decided to carry an aeroplane or seaplane to assist in aerial observations and to be used as the “eyes” of the expedition in the South. Flying machines had never before been used in Polar exploration, and there were obvious difficulties in the way of extreme cold and lack of adequate accommodation, but after consultation with the Air Ministry it was thought possible to overcome 8 them. The machine ultimately selected was a “Baby” seaplane, designed and manufactured by the Avro Company.

One of the first things done by Sir Ernest Shackleton in preparing for the northern expedition had been the purchase of a small wooden vessel of 125 tons, named the Foca I. She was built in Norway, fitted with auxiliary steam-engines of compound type and 125 horse-power. She was originally designed for sealing in Arctic waters, the hull was strongly made, and the timbers were supported by wooden beams with natural bends of enormous strength. The bow was of solid oak sheathed with steel. Her length was 111 feet, beam 23 feet, and her sides were 2 feet thick. Her draught was 9 feet forward and 14 feet aft. She was ketch-rigged, and was reputed to be able to steam at seven knots in still water and to do the same with sail only in favourable winds.

At the happy suggestion of Lady Shackleton she was re-named the Quest.

Sir Ernest received what he considered the greatest honour of his life. The Quest as his yacht was elected to the Royal Yacht Squadron. Perhaps a more ugly, businesslike little “yacht” never flew the burgee, and her appearance must have contrasted strangely with the beautiful and shapely lines of her more aristocratic sisters.

She was brought to Southampton in March, 1921, and placed in the shipyards for extensive alterations. The work was greatly impeded by the strike of ship workers, the general coal strike which occurred at that time, and by difficulties generally with labour, which was then passing through a very critical period. 9

It had been intended to take out the steam-engines and substitute an internal combustion motor of the Diesel type, but owing to the difficulties mentioned this had to be abandoned, and on the advice of the surveying engineer in charge of the work the old engines were retained. The bunker space was readjusted at the expense of the fore-hold, allowing a carrying capacity of 120 tons of coal, and giving a steaming radius which, with economy and use of sail, was estimated at from four to five thousand miles.

This work was in process when it became necessary to alter the plans of the expedition, and Sir Ernest realized that the Quest, which had been considered eminently suitable for the northern scheme, was not so well adapted for the long cruise in southern waters. It was impossible at this stage to change the ship, but further alterations were made on deck and in the rigging generally to adapt her for the new conditions.

Two yards were fitted, a topsail yard, 39 feet in length, and a foreyard to carry a large squaresail, 44 feet in length. The mizen-mast was lengthened to give a greater clearance to the wireless aerials. The existing bridge was enlarged, carried across the full breadth of the ship, and completely enclosed with windows of Triplex glass. The roof formed an upper bridge open to the air. To improve the accommodation, which was inadequate, a deck-house, 12 feet by 20 feet, was erected on the foredeck. It contained five rooms: four small cabins, and a room for housing hydrographical and meteorological instruments. New canvas and running gear was fitted throughout, and no expense spared to make her sound and seaworthy. Mr. Rowett was absolutely insistent that everything about the ship must be such as to ensure her 10 safety and the safety of all on board in so far as it was humanly possible. To everything in connexion with the ship herself Sir Ernest, as an experienced seaman, gave his personal attention. The work of the engine-room, which, as he was not an engineer, he was not able to supervise directly, was entrusted to a consulting engineer.

The Quest, though strong and well equipped, was small, and consequently accommodation generally was limited and living quarters were somewhat cramped. The forecastle was fitted as a small biological laboratory and geological workroom. In it were a bench for the naturalist and numerous cupboards for the storing of specimens. Leading from it on one side was a small cabin with two bunks for the naturalist and photographer respectively, and on the other was the photographic dark room.

The amount of gear placed aboard the ship was large, and the greatest ingenuity was required to stow it satisfactorily.

Two wireless transmitting and receiving sets, of naval pattern, were installed under the immediate supervision of a wireless expert, kindly lent to us by the Admiralty. The current for them was supplied by two generators, one a steam dynamo producing 220 volts, and a smaller paraffin internal-combustion motor producing 110 volts. The Quest being a wooden vessel, there was great difficulty in providing suitable “earthing.” For this purpose two copper plates were attached to either side of the ship below the water-line.

The more powerful of these sets was never very satisfactory, and we ultimately abandoned its use. The smaller proved entirely satisfactory for transmitting at 11 distances up to 250 miles. The receiving apparatus was chiefly of value in obtaining time signals, which are sent out nightly from nearly all the large wireless stations, and which we received at distances up to 3,000 miles. By this means we were frequently able, whilst in the South, to check our chronometers; but atmospheric conditions in those regions were very bad, and by producing loud adventitious noises in the ear-pieces interfered so much with the clarity of sounds that the obtaining of accurate signals was generally impossible.

A Sperry gyroscopic compass was installed, the gyroscopic apparatus being placed in the deck-house, with repeaters in the enclosed bridge and on the upper bridge. The dials were luminous, so that they could be read at night. This apparatus has the advantage that it is independent of immediate outside influences. It is usually supposed that at 65° north or south it ceases to be effective, but we found that the directive force was still sufficient at 69° south. It is interesting to note that this compass was designed by a German scientist to enable a submarine to reach the North Pole. It has been of the greatest use to ships in a general way, but for the one specific purpose for which it was designed it proved to be useless owing to the loss of directive power at the Poles. We found that bumping the ship through ice caused derangement, and as the compass took several hours to settle down again to normal, it proved ineffective whilst we were navigating through the pack.

Fitted into the enclosed bridge and looking forward were two Kent clear-view screens. They were electrically driven. They proved, when running, to be absolutely effective against rain, snow or spray.

The ship was fitted throughout with electric lighting, 12 including the navigating lights. Whilst in the South, however, the necessity for economy of fuel forbade the use of electricity and we had recourse to oil lamps. As we were then completely out of the track of shipping, navigating lights were not used.

Two sounding machines were installed, one an electrically-driven Kelvin apparatus for depths up to 300 fathoms. To obtain accurate soundings whilst the ship was under way, the sinker was fitted to carry sounding tubes, and had also an arrangement for indicating the nature of the bottom, whether rock, shingle or sand. For deep-sea work we had a Lucas steam-driven machine, which was affixed to a special platform on the port bow and supplied by a flexible tube from the steam pipe feeding the forward winch. This apparatus registered depths to four miles. Sounding with it was often difficult on account of the swell and the liveliness of the Quest, but the machine itself gave every satisfaction. The wire used with the Lucas machine was Brunton wire in coils of 6,000 fathoms, diameter .028, weight 12.3 lbs. per 1,000 fathoms, with a breaking strain of 200 lbs.

The meteorological equipment included:

Screens, containing wet and dry bulb thermometers, placed in exposed positions on the upper bridge.

One large screen, containing hair hygrograph, standard thermometer and thermograph.

(The heavy seas which broke over the ship and flung sprays over the upper bridge greatly interfered with the efficient working of these instruments by encrusting them with salt, and necessitated constant cleaning.)

Hydrometers, for determining the specific gravity of sea-water, which gives a measure of the total salinity. 13

Sea-thermometers, for determining the surface temperatures of the sea-water.

Marine pattern mercury barometer.

Aneroid barometers, checked daily from the mercury barometer, in case the latter should be broken.

Barograph, to obtain continuous records of the air pressure.

For upper-air work four cylinders of hydrogen and several hundred pilot balloons were taken. (These latter were sent up on many occasions from the ship, but the Quest proved to be so lively that it was impossible to keep them in the field of view of a telescope or even of field-glasses.)

All the instruments were very kindly lent to us by the Meteorological Section of the Air Ministry, and were of standard make and pattern.

We carried a good set of sextants, theodolites, dip circles and other accurate surveying instruments.

Several chronometers of different makes and patterns were placed aboard. Two of them, specially rated for us by Mr. Bagge, of the Waltham Watch Company, gave excellent results and, in spite of the violent motion of the ship and the difficulty of keeping a uniform temperature, maintained a remarkably even rating.

The medical equipment was designed for compactness and all-round usefulness.

Sledges, harness, warm clothing, footgear and an amount of scientific equipment were forwarded to Cape Town and warehoused to await the arrival of the Quest.

The greatest difficulty was experienced in the housing of the seaplane, but, after dismantling wings and floats, room was eventually found for it in the port alleyway, which it almost filled. 14

Sir Ernest Shackleton, as has already been said, in choosing his personnel selected first of all a nucleus of well-tried and experienced men who had served with him before, appointing me as second in command of the expedition. They included Worsley, Macklin, Hussey, McIlroy, Kerr, Green and McLeod. Applications for the remaining posts came in thousands, and many women wrote asking if a job could be found for them, offering to mend, sew, nurse or cook.

Two other men with previous experience were obtained: Wilkins, who served with the Canadian Arctic Expedition under Stefansson, and Dell, who had served with Captain Scott in the Discovery, and was thus known to Sir Ernest Shackleton and myself. Lieut.-Commander Jeffrey, an officer of the Royal Naval Reserve, who had served with distinction during the war, was appointed navigating officer for the ship. Major Carr, who had gained much experience of flying as an officer of the R.A.F., was appointed in charge of the seaplane.

A geologist was required, the selection falling upon G. V. Douglas, a graduate of McGill University, whom Sir Ernest had met in Canada.

Mr. Bee Mason was appointed photographer and cinematographer.

Amongst the remainder there was need of a good boy. Sir Ernest conceived the idea of throwing the post open to a Boy Scout, and the suggestion was taken up with the greatest enthusiasm by the Boy Scout organization. The post was advertised in the Daily Mail, and immediately a flood of applications poured in from every part of the country. These were finally filtered down to the ten most suitable, and the applicants were instructed to assemble in London, the Daily Mail 15 making the necessary arrangements and defraying the costs. These ten boys all had excellent records, and Sir Ernest, in finally making his selection, was so embarrassed in his choice that he selected two. They were J. W. S. Marr, an Aberdeen boy, and Norman E. Mooney, a native of the Orkneys.

There remained but three places to fill: C. Smith, an officer of the R.M.S.P. Company, was appointed second engineer; P.O. Telegraphist Watts, wireless operator; and Eriksen, a Norwegian by birth, was taken on as harpoon expert.

Sir Ernest, in order fully to carry out his programme, was anxious to leave England not later than August 20th, but owing to a general strike of ships’ joiners, dilatory workmanship and other unavoidable causes, the sailing was postponed well beyond that date.

At length all was ready; food stores and equipment, which included not only the highly technical and specialized Antarctic gear, but also such minute details as pins, needles and pieces of tape, were placed on board, and the ship was ready for sea.

The new expedition had been organized, equipped and got ready for departure all within three months. There are few who will realize what this means. No other man than Sir Ernest would have attempted it, and no other could have accomplished it successfully. It was, as he often said himself, only through the staunch support and active co-operation of Mr. Rowett, who aided and encouraged him throughout this period, that he was able to leave England that year. Postponement at such an advanced stage was impossible, and would have meant the total abandonment of the expedition. We left London finally on September 17th, 1921. 16

We dipped our ensign in a last farewell to London as we passed out from St. Katherine’s Dock, and turned our nose down-river for Gravesend, a tiny vessel even amongst the small shipping which comes thus far up the river. We were accompanied on this part of our journey by Mr. Rowett, who had taken a keen personal interest in everything connected with the expedition. Enthusiastic crowds cheered us at the start, and everybody we met wished us “Good luck and safe return.” The ensign was kept in a continuous dance answering the bunting which dipped from the staffs of every vessel we met. Ships of many maritime nations were collected in this cosmopolitan river, and these, too, joined in wishing success to our enterprise.

At Gravesend Mr. Rowett left us, and Sir Ernest returned with him to London with the object of rejoining at Plymouth. A strong north-easterly wind was blowing, and we lay for the night off Gravesend. In the small hours of the morning we were startled from sleep by the watchman crying, “The anchor’s dragging!” and turned out to find that we were bearing down on a Thames hopper that was moored near by. The Quest would not answer her helm, and before we were able to bring her up she had fouled the stays of the hopper with her bowsprit. Pyjama-clad figures leapt 17 from their bunks, and in the dim light presented a curious spectacle. Two or three of our men jumped on to the deck of the hopper, and by loosening a bolt succeeded in letting go one of her stays, when we swung free.

Kerr rapidly raised a sufficient pressure of steam in the boilers to get the engines going, and we soon regained control.

We brought up with our anchor, which had been acting as a dredge, the most amazing collection of stuff, which gave an interesting sidelight on the composition of the Thames floor.

No damage was received beyond a chafe to the bowsprit. We were anxious, however, to leave with everything in good order, and so proceeded to Sheerness Dockyard, where a new spar was put in for us by the naval authorities with a promptness and dispatch that contrasted strongly with the dilatory methods employed previously in the shipyards.

We had an exceptionally fine trip down Channel under the pilotage of Captain F. Bridgland, who was an old friend of ours, having taken the ship from Southampton to London.

We reached Plymouth on the 23rd, and were joined there by Sir Ernest Shackleton and Mr. Gerald Lysaght, a keen yachtsman, who had been invited to accompany us as far as Madeira. The Boss brought with him an Alsatian wolf-hound puppy, a beautiful well-bred animal with a long pedigree, which had been presented to him by a friend as a mascot. “Query,” as he was named, quickly became a fast favourite with all on board. Mr. Rowett also came from London to see us off, and we had with him a last cheery dinner. He was very popular 18 with all of us, for in addition to his support of expedition affairs he had taken a personal interest in every member of the company.

On the 24th we steamed out into the Sound and moored to a buoy, where the ship was swung and the compasses adjusted by Commander Traill-Smith, R.N., who kindly undertook this important work. The Admiralty tug used to swing the Quest accentuated her smallness, for she was many times our size and towered high above us.

This task completed, we put out to sea, pleased, as Sir Ernest Shackleton said at the time, to be making our final departure from a town that has ever been associated with maritime enterprise.

The following extracts are from Sir Ernest Shackleton’s own diary:

Saturday, September 24th, 1921.

At last we are off. The last of the cheering crowded boats have turned, the sirens of shore and sea are still, and in the calm hazy gathering dusk on a glassy sea we move on the long quest. Providence is with us even now. At this time of equinoctial gales not a catspaw of wind is apparent. I turn from the glooming immensity of the sea and, looking at the decks of the Quest, am roused from dreams of what may be in the future to the needs of the moment, for in no way are we shipshape or fitted to ignore even the mildest storm. Deep in the water, decks littered with stores, our very life-boats receptacles for sliced bacon and green vegetables for sea-stock; steel ropes and hempen brothers jostle each other; mysterious gadgets connected with the wireless, on 19 which the Admiralty officials were working up to the sailing hour, are scattered about. But our twenty-one willing hands will soon snug her down.

A more personal and perplexing problem is my cabin—or my temporary cabin, for Gerald Lysaght has mine till we reach Madeira—for hundreds of telegrams of farewell have to be dealt with. Kind thoughts and kind actions, as witness the many parcels, some of dainty food, some of continuous use, which crowd up the bunk. Yet there is no time to answer them now.

We worked late, lashing up and making fast the most vital things on deck. Our wireless was going all the time, receiving messages and sending out answers. Towards midnight a swell from the west made us roll, and the sea lopped in through our washports. About 1 a.m. the glare of the Aquitania’s lights became visible as she sped past a little to the southward of us, going west, and I received farewell messages from Sir James Charles and Spedding.[1] I wish it had been daylight.

At 2 a.m. I turned in. We are crowded. For in addition to McIlroy and Lysaght, I have old McLeod as stoker.

Sunday, September 25th.

Fair easterly wind; our topsail and foresail set. All day cleaning up with all hands. We saw the last of England—the Scilly Isles and Bishop Rock, with big seas breaking on them; and now we head out to the west to avoid the Bay of Biscay. With our deep draught we roll along like an old-time ship, our foresail 20 bellying to the breeze. The Boy Scouts are sick—frankly so, though Marr has been working in the stokehold until he really had to give in. Various messages came through. To-day it has been misty and cloudy, little sun. All were tired to-night when watches were set.

Monday, 26th. 47° 53´ N., 9° 00´ W.

A mixture of sunshine and mist, wind and calm. Passed two steamers homeward bound, and one sailing ship was overhauling us in the afternoon, but the breeze fell light, and she dropped astern in the mist that came up from the eastward. Truly it is good to feel we are starting well, and all hands are happy, though the ship is crowded.

Two hands have to help the cook, and the little food hatchway is a blessing, for otherwise it is a long way round. Green is in his element, though our decks are awash amidship. He just dips up the water for washing his vegetables.

With a view to economy he boiled the cabbage in salt water. The result was not successful.

The Quest rolls, and we find her various points and angles, but she grows larger to us each day as we grow more used to her. I asked Green this morning what was for breakfast. “Bacon and eggs,” he replied. “What sort of eggs?” “Scrambled eggs. If I did not scramble them they would have scrambled themselves”—a sidelight on the liveliness of the Quest. Query, our wolf-hound puppy, is fast becoming a regular ship’s dog, but has a habit of getting into my bunk after getting wet.

We are running the lights from the dynamo, 21 and, when the wireless is working, sparks fly up and down the backstays like fireflies. A calm night is ours.

Tuesday, 27th—Wednesday, 28th.

43° 52´ N., 11° 51´ W. 135 miles.

Another fine day. Not much to record. All hands engaged in general work on the ship. In the afternoon the mist arose and the wind dropped. At night the wind headed us a bit, and we took in the topsail. Marr was at the wheel in the first watch, and did well. Mooney, at present, is useless. A gang of the boys were employed turning the coal into the after-bunkers—a black and dusty job; but they were quite happy. We passed a peaceful night. This morning the wind practically dropped. What little there was came out ahead, so we took in all sail. The Quest does not steam very fast, 5½ being our best so far. This rather makes me think, and may lead to alterations in our plans, for we must make our time right for entering the ice at the end of December, and may possibly have to curtail some of our island work or postpone it until we come out of the South. This morning we are in glorious sunshine—the sea sapphire-blue and a cloudless sky; but, alas! noon, in spite of our pushing, gives us only 135 miles. We have allowed a current of 7 miles N. 12° W.

Gerald Lysaght is one of our best workers, and takes long spells at the wheel. Occasionally little land-birds fly on board, and our kittens take an interest in them, as yet unknowing their potential value as food or game (?). How far away already we seem from ordinary life! 22

I stopped the wireless last night. It is of no importance to us now in a little world of our own.

Wednesday, 28th—Thursday, September 29th, 1921. Lat., 42° 9’ N. Long., 13° 10’ W. Dist., 116’.

A strong wind, with high seas and S.S.W. swell; strong squalls were our portion. The ship is more than lively and makes but little way. She evidently must be treated as a five-knot vessel dependent mainly on fair winds, and all this is giving me much food for thought, for I am tied to time for the ice. I was relieved that she made fairly good weather of it, but I can see that our decks must be absolutely clear when we are in the Roaring Forties. Her foremast also gives me anxiety. She is not well stayed, and I think that the topsail yard is a bit too much. The main thing is that I may have to curtail our island programme in order to get to the Cape in time. Everyone is cheerful, which is a blessing, all singing and enjoying themselves, though pretty well wet; several are a bit sick. The only one who has not bucked up is the Scout Mooney. He seems helpless, but I will give him every chance. I can see also that we must be cut down in crew to the absolutely efficient and only needful for the southern voyage.

Douglas is now stoking and doing well. It will, of course, take time to square things up and for everyone to find themselves; she is so small. It is only by constant thought and care that the leader can lead. There is a delightful sense of freedom from responsibility in all others; and it should be so. These are just random thoughts, but borne in on one as all being so different from the long strain of preparation. 23 It is a blessing that this time I have not the financial worry or strain to add to the care of the active expedition. Lysaght is doing very well, and so is the Scout Marr.

Sir Ernest Shackleton’s diary ends at this point, and there are no other entries till January 1st, 1922.

We now began to settle down to our new conditions of life.

In the deck-house were five small cabins. The Boss and I had the two after ones, but at this time Mr. Lysaght, or the “General” as he was called by all of us (like most nicknames, for no particular reason), occupied one of them, whilst the Boss and I shared the other.

Worsley and Jeffrey had a cabin running the full breadth of the house and the roomiest in the ship, but it had also to act as chart-room. Macklin and Hussey occupied a tiny room of six feet cubed on the starboard side, which contained the medicine cupboard. Here, in spite of restricted space, they dwelt in perfect harmony, due, as they were wont to say, “to both of us being non-smokers.” They were known collectively as “Alphonse and D’Aubrey,” but how the names originated it is impossible to say, for though the versatile Londoner might at times have passed as a Frenchman, the same could not be said for the more phlegmatic Scot.

The corresponding room on the port side housed the meteorological instruments and the gyroscopic compass.

Wilkins and Bee Mason had bunks in the converted forecastle, which contained the photographic dark room, a work bench for the naturalist, and numerous cupboards for the storing of specimens. Wilkins, an old campaigner, had used much foresight and ingenuity in 24 fitting it up, and had utilized the limited space to the utmost advantage. Their cabin was indeed a dim recess and at first proved very stuffy, but before we were many days out Wilkins had designed and fitted an air-shoot, which acted very well and enormously improved the ventilation. Green, the cook, had a cabin beside his galley, which was always warm from the heat of the engine-room—too much so to be comfortable in temperate climes, but he looked forward to the advantage he would derive when we entered the cold regions. All the others lived aft and occupied bunks which were situated round the mess-room and opened directly into it, unscreened except by small green curtains, which could be drawn across when the bunks were unoccupied. It was by no means a pleasant or convenient arrangement, but, with the small size of the ship and general lack of space, the only one possible under the circumstances. The mess-room itself was small, boasting the simplest of furniture: two plain deal tables, four forms, a cupboard for crockery, and a small sideboard. At the foot of the companion-way was a rack of ten long Service rifles. Two of the forms were made like boxes with lids, to act as lockers.

The seating accommodation just admitted all hands to sit together, not counting the cook and the cook’s mate and four men who were always on watch. They sat down to a second sitting. The food was of good quality, plain, and simply cooked. Three meals a day were served: breakfast, lunch, and supper. The Boss presided, and under his cheery example the new hands soon learned to make light of the strange and rather uncomfortable conditions.

Every day for breakfast we had Quaker oats, with 25 brown sugar or syrup (salt for the Scotsmen) and milk, followed by bacon, with eggs (as long as they lasted), afterwards sausage or some equivalent, bread or ship’s biscuit, marmalade, and tea or coffee.

For lunch we usually had a hot soup, followed by cold meat, corned beef, tongue or tinned fish, and bread or biscuit, cheese, jam and tea.

Supper consisted of a hot meat dish, with vegetables, followed by some sort of pudding, bread or biscuit, and tea.

The galley was small, and contained a diminutive range and a number of shelves fitted with battens to prevent things flying off with the roll of the ship. The oven accommodation was small, and admitted of the cooking of one thing only at a time. Here Green reigned over his pots and pans, which, owing to the motion of the ship, proved more often than not to be elusive and refractory.

At meal-times the dishes were passed through a large window port into the messroom by the cook’s mate, and received by the “Peggy” for the day, who served the food and waited at table. Duty as “Peggy” was performed by each man in turn (with the exception of the watch-keeping officers), who also washed the dishes, cleaned the tables, and generally tidied up after each meal. Sir Ernest Shackleton had made it plain to all hands that no work was to be considered too humble for any member of the expedition.

Table-cloths were never used, but the tables were well scrubbed daily, so that they soon took on a fine whiteness. Fiddles were a permanent fitting except when we were in port, for the Quest never permitted us to do without them at sea, whilst in the worst weather 26 even they proved useless to prevent table crockery from being thrown about.

In addition to Query there were on the ship two other pets in the form of small black kittens, one presented to us as a mascot by the Daily Mail, the other, I believe, the gift of a girl to one of the crew. They suffered a little at first from sea-sickness, but soon developed the most voracious appetites, and showed the greatest persistence in coming about the table for food. They clambered up one’s legs with long sharp claws, “miaowed,” and at every opportunity put their noses into jugs and plates. No amount of rebuffs had any effect upon them, and they had a curious preference for food on the table to that which was placed for them in their own dishes. Two more importunate kittens I have never seen. It is to be feared that one or two of the party slyly encouraged them, for we could never cure them of their bad habits.

The companion steps leading from the scuttle to the messroom were very steep, and at this time Query had not learned the art of going up and down, though he acquired it later. It used to be a common sight to see his handsome head framed in the opening of the window port through which Green passed the food, gazing wistfully at the dainty morsels which were being transferred to other mouths.

These first days with the Boss were very cheery ones, and I like to look back on them. There was little refinement on the ship and more than ordinary discomfort, yet each meal-time was a happy gathering of cheery souls, and conversation crackled with jokes, in the perpetration of which Hussey was by no means the least guilty. The strain of preparation had been a heavy 27 one, and Sir Ernest seemed to be enjoying the quiet, the freedom and the mental peace of our small self-contained little world. I think he liked to find himself surrounded by his own men, and he was always at his best when he had a definite objective to go for.

There is something about life at sea, and the companionship of men who have lived untrammelled lives free from the restraints of convention, that I find hard to describe. I think it must be that it is more primitive. Certainly, one drops into it with a contentment that contrasts strongly with the feeling of effort with which one braces oneself to meet the more conventional circumstances of the return to civilized life. It is, I suppose, a matter of heredity and transmitted instinct which makes falling back to the primitive more easy than progress, meaning by “progress” the advance of artificiality and the tremendous speeding up of modern existence. Some such instinct must be present, for what else is there to tempt one from a cosy fireside and the morning paper?

We kept three watches, the watch-keeping officers being Worsley, Jeffrey and myself. The Boss kept no particular watch, but was always at hand to give instructions and take charge on special occasions. In my watch were McIlroy, Macklin and Hussey; in Worsley’s, Wilkins, Douglas and Watts; in Jeffrey’s, Carr, Eriksen and Bee Mason. Dell and McLeod acted as stokers. The two Scouts were at first employed in a generally useful capacity, helping the cook and lending a hand wherever required. In addition to his deck duties, each man had his own particular job to attend to. Before we had been out many days it became clear to all that in this trip we were to have no picnic, and that in life 28 on the Quest we would have to adapt ourselves to all sorts of discomforts and inconveniences. However, we were committed to our enterprise, our work lay before us, and we settled down cheerfully to make the best of things.

A few extracts from the official diary will give an indication of conditions about this time.

Tuesday, September 27th.

The wind came round to S.E. and freshened up during the day. The Quest is behaving badly in the short head seas. We have had to take in sail and are proceeding under steam, making poor progress. Bee Mason and Mooney are rather off colour.

September 28th.

The wind has increased, with heavier seas. During the day the engines were stopped for adjustment. Kerr says the crank shaft is out of alignment, and expects further trouble. This happening so early in the voyage does not promise well for the trip, for, as the Boss says, we are already late and cannot afford much time in port.

September 30th.

A moderate gale blowing from the S.W. We made no headway into it, and the Boss decided to heave to with the engines at slow speed. This has given us an idea of the Quest’s behaviour in bad weather. The Boss is pleased with her sea-going qualities, for in spite of fairly heavy seas she has remained dry, taking aboard very little water.[2] She 29 has a lively and very unpleasant motion, which has induced qualms of sea-sickness in many of the “land lubbers.” Bee Mason and young Mooney are hors de combat. They are both plucky. The Scout makes no complaint, but it is obvious that life to him just now is a terrible misery. He has tried hard to carry on his work. We wish we could do something for him, but there is little comfort on the ship.

October 2nd.

Head winds have continued to blow, against which we have made little headway. The engines have developed a nasty knock which is appreciable to all on the ship. Kerr insists that an overhaul is necessary, and Sir Ernest has decided to make for Lisbon. We accordingly headed up for “The Burlings,” and picked up the light about 6 p.m.

On October 3rd Kerr had to reduce the pressure of steam in the cylinders, as we were now proceeding slowly along the coast of Portugal in the direction of Cape Roca. The coast-line is very picturesque, dotted all along with old castles and pretty little windmills. We plugged slowly on, passed by many steamers which signalled us “A pleasant voyage,” to which we were kept busy answering “Thank you.” One of the beautiful modern P. & O. liners, coming rapidly up from behind, altered course to pass close to us, and we could not help envying her speed and comfort as, making nothing of the short steep seas in which we were rolling and pitching in the liveliest manner, she rapidly drew out of sight ahead.

Just before nightfall we reached Cascaes, at the mouth of the Tagus, where the pilot came aboard, but 30 decided not to proceed till daybreak. We lay at anchor for some hours, and I rarely remember a more uncomfortable period than we spent here, jerking at the cable with a short steep roll that made one positively giddy. It was more than the Portuguese pilot could stand, for he moved us farther up the river into shelter, enabling us to get the first comfortable sleep since leaving the Scilly Islands.

We were taken by tug up the fast-running Tagus to Lisbon in the early morning, and later the Quest went into dock.

The work was entrusted to Messrs. Rawes & Co., and put in hand without delay. The source of all the trouble in the engine-room proved to be the crank shaft, which was out of alignment, and thus caused the bearings to run hot. The high-pressure connecting rod was found to be badly bent. The rigging also was altered and reset up.

We did not get away from Lisbon until Tuesday, October 11th.

Those whose work did not confine them to the ship made the most of their time ashore, the first move being to a hotel for the luxury of a hot bath and a well-cooked dinner. We were warmly entertained by the British residents, who during the whole of our stay showed us the greatest kindness and hospitality. Mooney was carried off by the Boy Scouts of Lisbon, who showed him the sights of the place. Marr, although an enthusiastic supporter of the Boy Scout movement, did not care to spend his whole time as a “kilted spectacle for curious Latins,” and, doffing his uniform, accompanied the others in their movements. Amongst other things, we paid a visit en masse to a bull-fight, which we found to 31 be a much more humane undertaking than those carried out under the old Spanish system. The bull is not killed and, though goaded by the darts of the picadors to a fury, does not seem to be subjected to great ill-treatment. The horses, instead of being old screws meant to be gored, are beautiful animals, which the matadors take the greatest care to protect.

We had many visitors on board the ship, including the British and American Ministers, who were shown round by Sir Ernest. All, as in London, expressed their amazement at the size of the Quest, imagining her to be far too small for the undertaking.

We set out on October 11th for Madeira, having expended seven days of precious time.

On leaving the Tagus we again encountered strong head winds, which lasted four days, during which the Quest’s movements were such as to upset the strongest stomachs. Bee Mason and Mooney were once more hors de combat, and few except the hardened seamen amongst us escaped feeling ill, though they managed to carry on their work.

I think there must be very few people in these days of luxurious floating palaces that ever really have to endure the agonies of sea-sickness. If they do feel ill they can retire to their bunks, where attentive stewards minister to their wants. Few, however, have been in such a condition that they dared not take to their bunks, but have spent days and nights on deck, sleepless, sodden and cold, in a vigil of misery unbroken save to turn to when “eight bells” announces the watch, and struggle through the work until the striking of the bells again announces relief, unable to taste or bear the thought of food, and with a stomach persistently and 32 painfully rebellious in spite of an aching void. Such is the fate of those who go to sea in small vessels, without stewards and without comforts, and where there is work to be done. I have nothing but admiration for the way some of the sea-sick men were sticking to their jobs. Among them was Marr, the Boy Scout, who showed the greatest hardihood and pluck.

Winds continued to blow from ahead till, on October 15th, the weather changed and we had a beautiful clear day, with little wind or sea and bright sunshine. Mooney and Bee Mason continued to suffer from sea-sickness all the way, the latter becoming quite ill with a high temperature. As the conditions we had met were likely to prove mild as compared with those we would encounter in the stormy southern seas, Sir Ernest Shackleton decided to send both of them home from Madeira. Let it be said here that it is probable that, if they had had their own way, each of them would have elected to continue with us, and this decision to send them back carries with it absolutely no stigma, for they showed extraordinary pluck and bore their trials uncomplainingly. To Mooney especially, a young boy gently nurtured, who had never before left his Orkney home, this portion of the trip must have meant untold misery. We greatly regretted losing both these companions.

Photo: Wilkins

A PORPOISE WHICH WAS HARPOONED FROM THE BOWSPRIT

On leaving Lisbon the Boss had put the other Scout, Marr, to work in the bunkers, where he went through a gruelling test. He came out of the trial very well, showing an amount of hardihood and endurance that was remarkable. He suffered from sea-sickness, but never failed to carry out his allotted task, and thoroughly earned his right to continue as a permanent member 33 of the expedition. I find in his diary the following entry:

I volunteered to go down the stokehold, and my first duty was that of trimming coal. It is a delightful occupation. It consists of going down to the bunkers and shovelling coal to within easy reach of the firemen. The bunkers are pitch black, and the air—well, there is no air, but coal dust. This gets into one’s ears, eyes, nose, mouth and lungs; one breathes coal dust. After I had trimmed sufficient coal, I commenced stoking. I got on fairly well for a first attempt, but did not like the heat.

Another entry which this boy made during the bad weather shows what he must have gone through, though nothing which he said at the time would have led one to suspect it:

Indeed, I was feeling more dead than alive ... what with the rolling of the ship and the unsteady nature of my limbs—I was sea-sick, and I was much afraid I should fall into the fire or down the bilges. When I came off (my watch) I immediately made for my bunk, where I remained, without partaking of my breakfast or dinner, until 12.0 noon, when I got up again for my next watch....

Before leaving England the Boss had ordered a brass plate to be made, on which was inscribed two verses of Kipling’s immortal “If?” and had it placed in front of the bridge. Hussey, after a heavy day’s coaling in bad weather, was inspired to a version specially applicable to the Quest, which reads as follows: 34

If you can stand the Quest and all her antics,

If you can go without a drink for weeks,

If you can smile a smile and say, “How topping!”

When someone splashes paint across your “breeks”;

If you can work like Wild and then, like “Wuzzles,”

Spend a convivial night with some “old bean,”

And then come down and meet the Boss at breakfast

And never breathe a word of where you’ve been;

If you can keep your feet when all about you

Are turning somersaults upon the deck,

And then go up aloft when no one told you,

And not fall down and break your blooming neck;

If you can fill the port and starboard bunkers

With fourteen tons of coal and call it fun,

Yours is the ship and everything that’s on it,

Coz you’re a marvel, not a man, old son....

We arrived at Madeira on the 16th. Kerr had again a number of adjustments to make in the engine-room, and, with Smith, toiled hard all the time we were in harbour.

Madeira has been a favourite stopping place for all expeditions to the Antarctic. Here on October 4th, 1822, Weddell was received and assisted by Mr. John Blandy, whose firm has rendered help to many subsequent expeditions. On this occasion we were welcomed by the present Mr. and Mrs. Blandy and visited their beautiful estate on the hill.

We left after a two days’ stay. “The General” was due to return from here, but he had made himself so universally popular that Sir Ernest persuaded him to go on as far as the Cape Verde Islands. Neither our discomforts nor the vagaries of the Quest had upset him in the slightest, and he had proved himself a useful member of the crew, taking a trick at the wheel and 35 carrying on the work on deck generally. We now entered fine weather, and, running comfortably before the north-easterly trade winds, reached St. Vincent on October 28th. The engines had continued to give trouble, and Kerr reported that extensive repairs and readjustments would be necessary before continuing farther. They were carried out quickly and effectively by Messrs. Wilson, Sons & Co., who acted as our agents, and most generously supplied us on leaving with one hundred tons of coal free of all charge.

We said good-bye to “General” Lysaght, whom we saw depart with genuine regret. We had a farewell dinner, at which was produced all the best the Quest could offer, and when the Boss proposed “The General!” we drank his health and wished him luck. Although he was returning to home and comforts, he would, I believe, had it been possible, have accompanied us farther on our way. At the conclusion he was presented with an illuminated card, the combined work of all the artists aboard, but chiefly, I think, of Wilkins, which bore the following poem composed by the Boss:

To Gerald Lysaght, A.B.

After these happy days, spent in the oceanways,

Homeward you turn!

Ere our last rope slipped the quay and we made for the open sea

You became one of us.

You have seen the force of the gale fierce as a thresher’s flail

Beat the sea white;

You have watched our reeling spars sweep past the steady stars

In the storm-wracked night.

You saw great liners turn; high bows that seemed to churn

The swell we wallowed in;

They veered from their ordered ways, from the need of their time kept days,

To speed us on. 36

Did envy possess your soul; that they were sure of their goal

Never a damn cared you,

For you are one with the sea—in its joy and misery

You follow its lure.

In the peace of Chapel Cleeve, surely you must believe,

Though far off from us,

That wherever the Quest may go; what winds blow high or low—

Zephyrs or icy gale:

Safe in our hearts you stand; one with our little band.

A seaman, Gerald, are you!

—E. H. S.

On the 28th we set out, making course for St. Paul’s Rocks. We enjoyed excellent weather, with smooth seas on which the sun sparkled in a myriad of variegated points. We felt the heat considerably, which is natural, considering the confined space and general lack of artificial means of keeping cool, such as effective fans, refrigerators and iced water. Most of us slept on deck, under the stars which twinkled above us, large and luminous, in the tropic nights.

The Boss took Marr out of the stokehold about this time and placed him to assist Green as cook’s mate, a not very romantic job, but one which he carried out with his usual thoroughness. He had by now thoroughly found his feet, and took a deep interest in the sea life of the tropics: flying fish fleeing in shoals before the graceful bonito, which, leaping in the air to descend with scarcely a splash, followed in relentless pursuit; dolphins, albacore and the sinister fins of occasional sharks.

On November 4th a large school of porpoises came about the ship and played around our bows. Eriksen seized the opportunity to harpoon one of them, which we hauled aboard. Wilkins found in its stomach a number of cuttle-fish beaks. The meat we sent to the 37 larder. The porpoise is not a fish, but a mammal, warm blooded and air breathing. It provides an excellent red meat, against which British sailors have for many years felt a strong prejudice, but which is eaten with relish by Scandinavians. We found it a pleasant change from tinned food.

One day we encountered a magnificent five-masted barque becalmed in the doldrums, all sail set and flapping gently with the slight roll. She was flying the French ensign, and on closer approach proved to be the La France, of Rouen. She presented such a beautiful sight,[3] with her tall masts and lofty spars reflected in the smooth sea, that we altered course to pass close to her and enable Wilkins to get some photographs. Sir Ernest spoke to her captain, who replied in excellent English, asking where we had left the trade winds, voicing what is the uppermost thought in the mind of every master of a sailing ship, the probability and direction of winds, on which depends their motive power.

We were amused to notice that though the Boss sent his voice unaided across the water with the greatest ease, the Frenchman required a megaphone to make audible his replies.

These beautiful vessels are fast being driven off the ocean in the competition with modern steamships, yet it is with a feeling of genuine regret that one sees them go, for with them departs much of the romance of the sea. The apprentice of to-day takes his training in steamers, and the modern seaman is beginning to regard sail as a “relic of barbarism.”[4] In the days when I first went to sea one might count masts and yards by the 38 hundred in harbours such as Falmouth or Queenstown, but now they are to be found only in ones and twos. They were fine ships, the old clipper ships, and bred a fine type of seaman, yet “the old order changeth,” and in spite of an attempt to bring them into general use again, it is to be feared that they will gradually die out altogether.

Early on the morning of November 8th we sighted St. Paul’s Rocks, standing solitary and alone in the midst of a wide tropic sea. They were the first objective, and Sir Ernest arranged for a party to land there. We lay to under their lee and dropped a boat. Immediately a countless shoal of sharks came about us, their fins showing above water in dozens on every side. A considerable swell was running, making the approach difficult, but we effected a landing in a little horseshoe-shaped basin lying in the midst of the rocks. Wilkins, assisted by Marr, took ashore camera and cinematograph apparatus, and was able to get some excellent photos of birds.

Douglas, assisted by Dell, carried out an accurate survey and made a geological examination of the rocks. Hussey and Carr carried out meteorological work, taking advantage of a fixed base to send up a number of balloons for measuring the upper air currents. I had charge of the boat, with Macklin, Jeffrey and Eriksen as crew.

We noticed that the cove in which we had made the landing was simply alive with marine life of every kind, and so returned to the ship for fishing tackle. For bait we used crabs, which swarm in large numbers all over the rocks. There were two sorts, a large red variety and a smaller one dark green in colour. They were evil-looking 39 things, and seemed always to be watching us intently, moving stealthily sideways, now in this direction, now in that. At the least sign of approach they darted with amazing rapidity into crevices in the rocks. Occasionally we saw them gather their legs under them and give the most extraordinary leaps of from two to three feet. Their jaws worked continually and water sizzled and bubbled at their mouths. Some of them had found flying fish which had flown ashore or been brought by the birds. It was a horrible sight—they tore the flesh into fragments with their powerful claws and crammed it into their mouths. The ownership was often disputed, the bigger crab always winning. Occasionally a small crab, hoping for some of the crumbs which might fall from the rich man’s table, would creep cautiously up behind. The bigger crab, however, permitted no depredations, but, waiting till the smaller one reached within a certain limit, would kick out suddenly with an unoccupied leg, causing the smaller one to hop hastily out of reach.