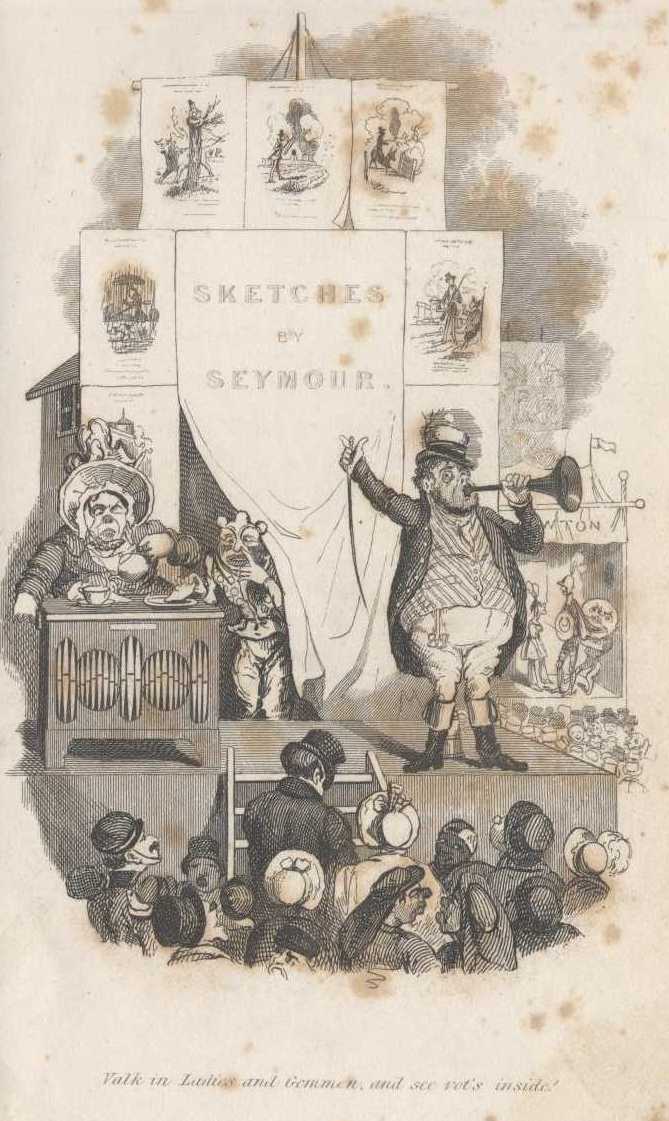

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Sketches of Seymour (Illustrated), Part 1., by Robert Seymour This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Sketches of Seymour (Illustrated), Part 1. Author: Robert Seymour Release Date: July 11, 2004 [EBook #5645] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SKETCHES OF SEYMOUR *** Produced by David Widger

EBOOK EDITOR'S INTRODUCTION:

"Sketches by Seymour" was published in various versions about 1836. The copy used for this PG edition has no date and was published by Thomas Fry, London. Some of the 90 plates note only Seymour's name, many are inscribed "Engravings by H. Wallis from sketches by Seymour." The printed book appears to be a compilation of five smaller volumes. From the confused chapter titles the reader may well suspect the printer mixed up the order of the chapters. The complete book in this digital edition is split into five smaller volumes—the individual volumes are of more manageable size than the 7mb complete version.

The importance of this collection is in the engravings. The text is often mundane, is full of conundrums and puns popular in the early 1800's—and is mercifully short. No author is given credit for the text though the section titled, "The Autobiography of Andrew Mullins" may give us at least his pen-name.

DW

| SCENE I. | Sleeping Fisherman. |

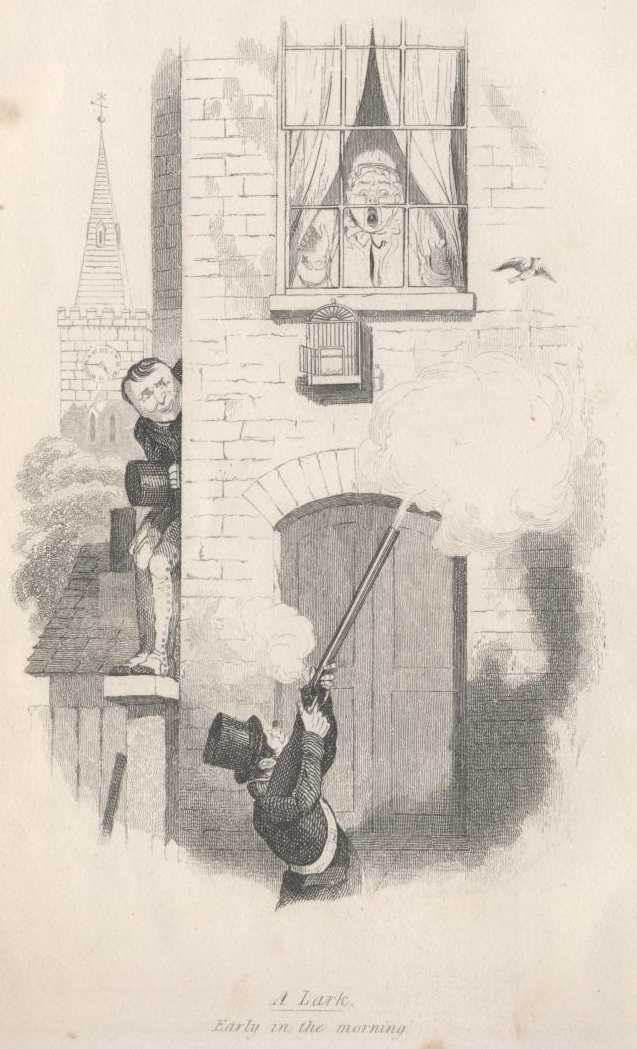

| SCENE II. | A lark—early in the morning. |

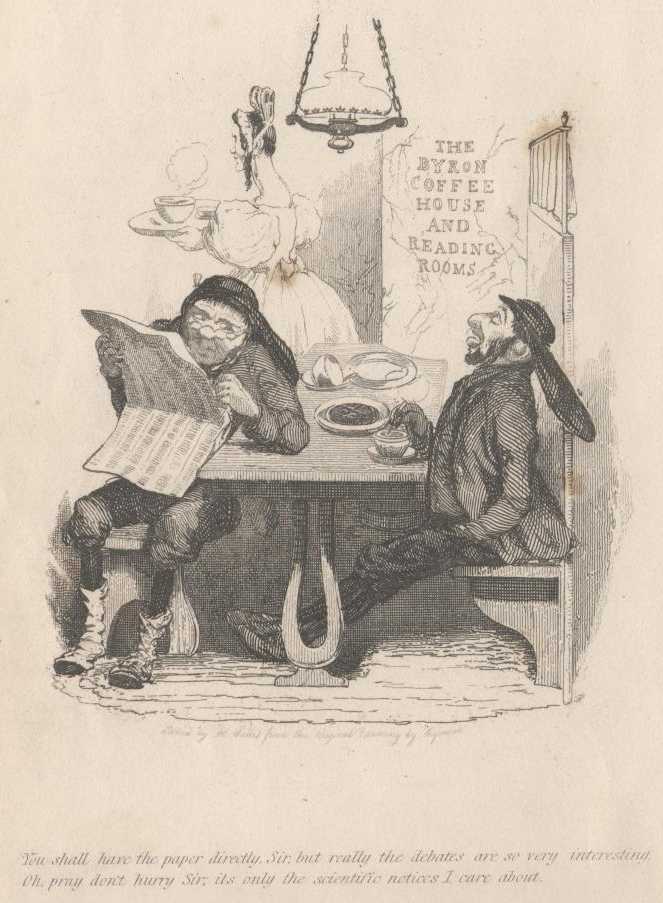

| SCENE III. | The rapid march of Intellect! |

| SCENE IV. | Sally, I told my missus vot you said. |

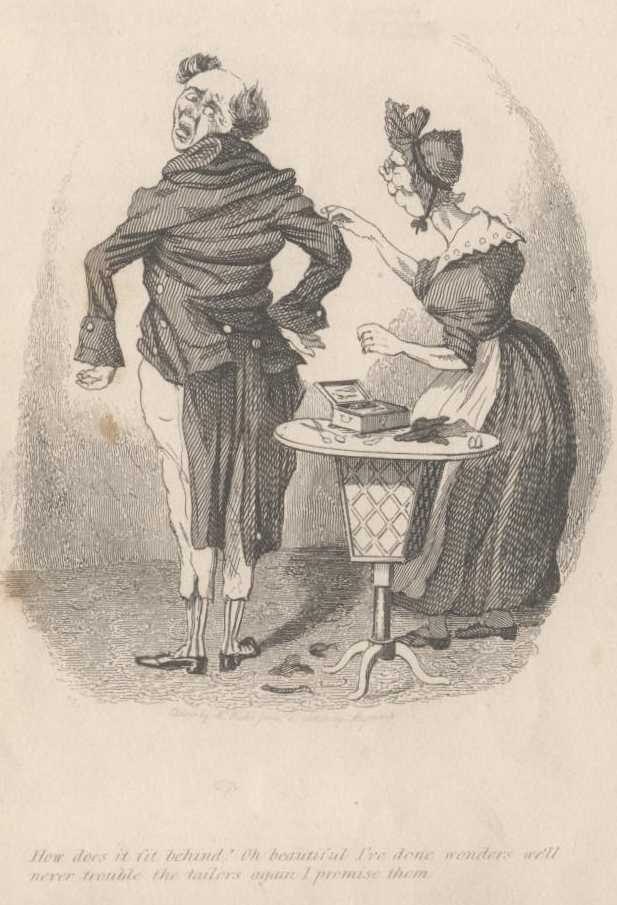

| SCENE V. | How does it fit behind? |

| SCENE VI. | Catching-a cold. |

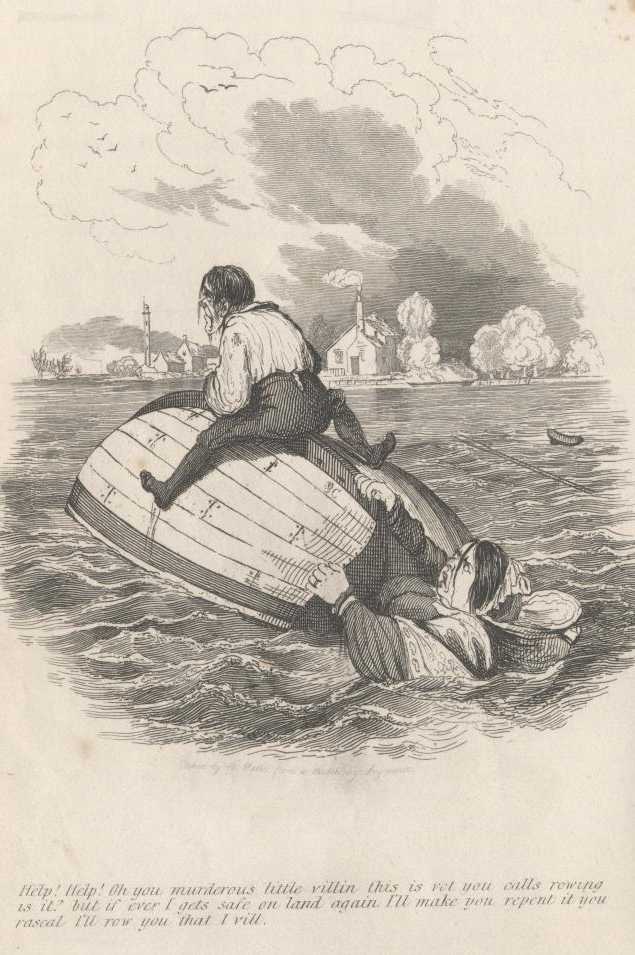

| SCENE VII. | This is vot you calls rowing, is it? |

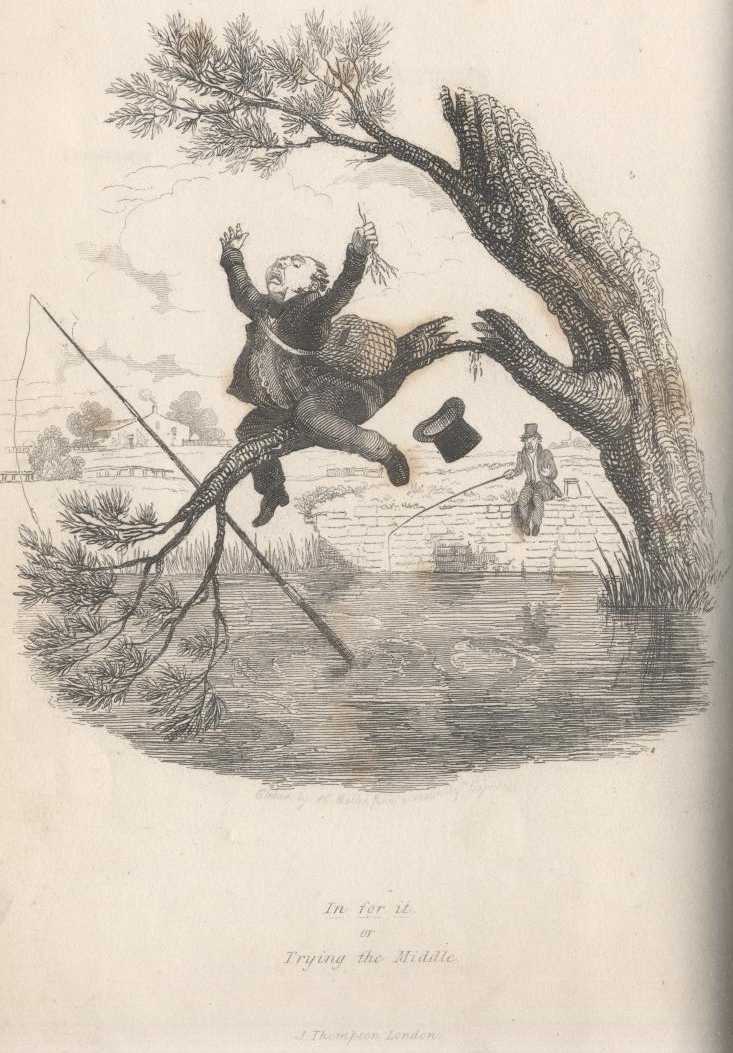

| SCENE VIII. | In for it, or Trying the middle. |

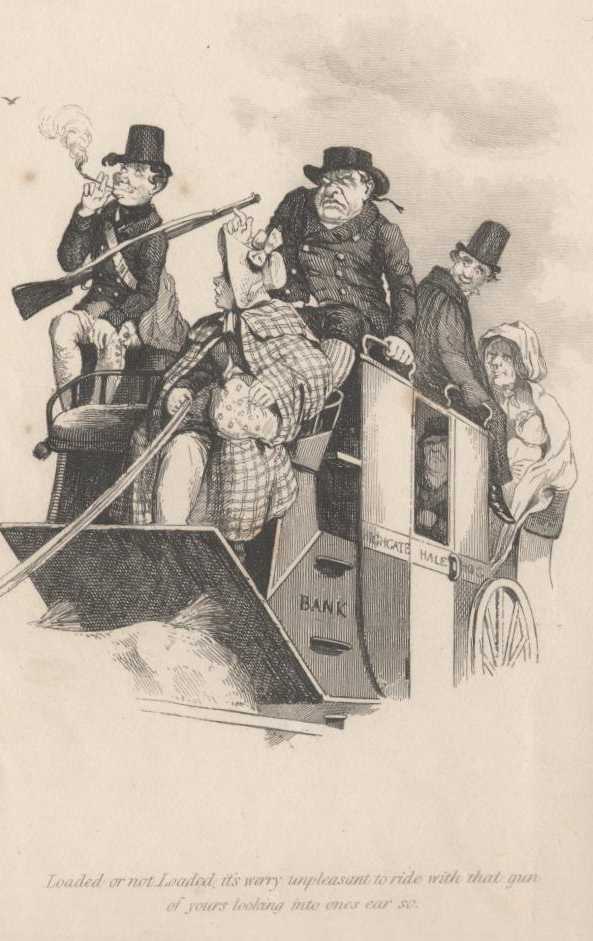

| CHAP. I. | The Invitation, Outfit, and the sallying forth |

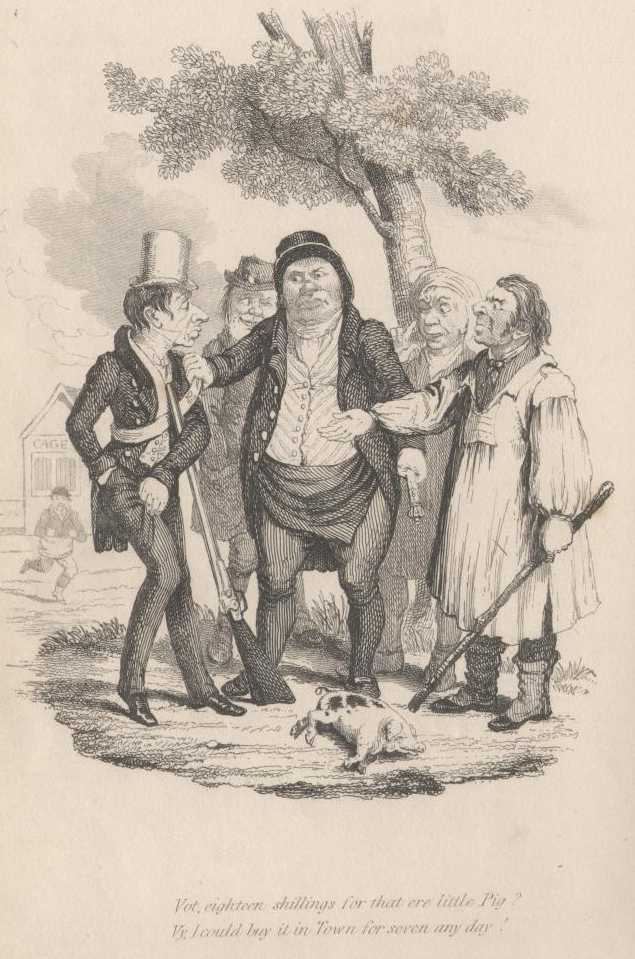

| CHAP. II. | The Death of a little Pig |

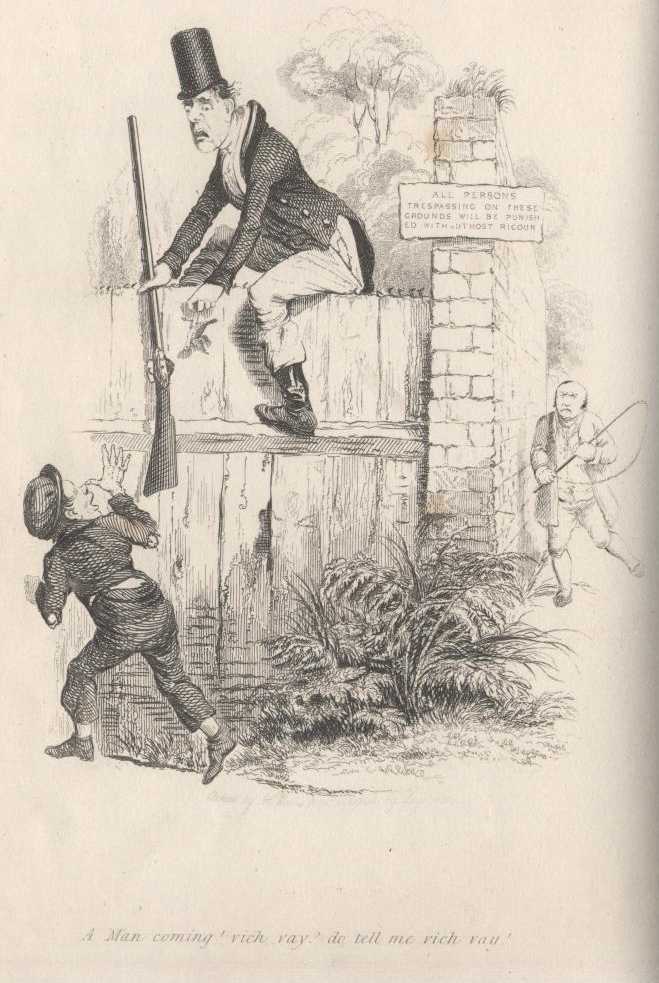

| CHAP. III. | The Sportsmen trespass on an Enclosure |

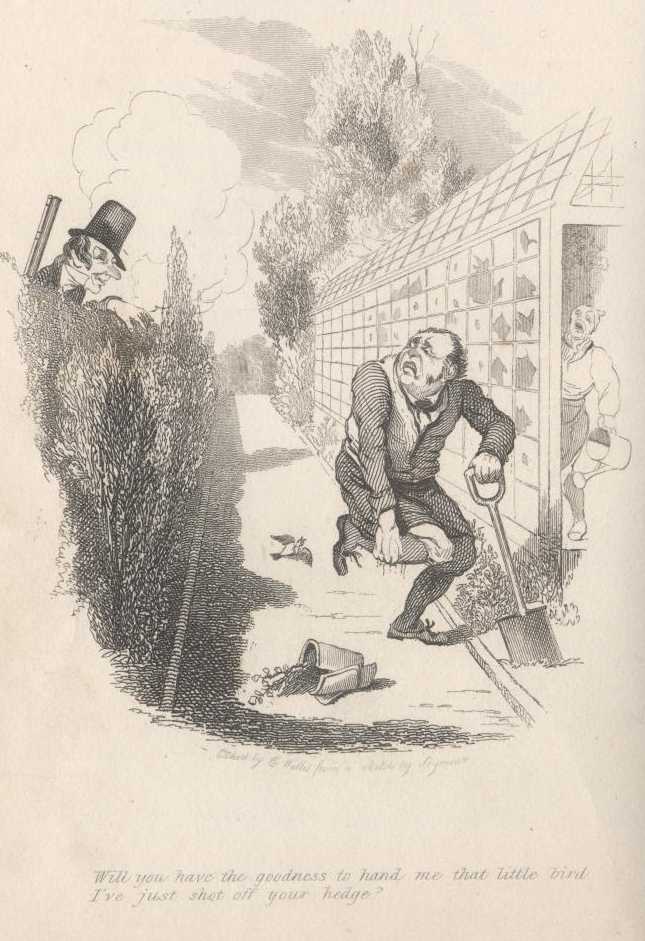

| CHAP. IV. | Shooting a Bird, and putting Shot into a Calf! |

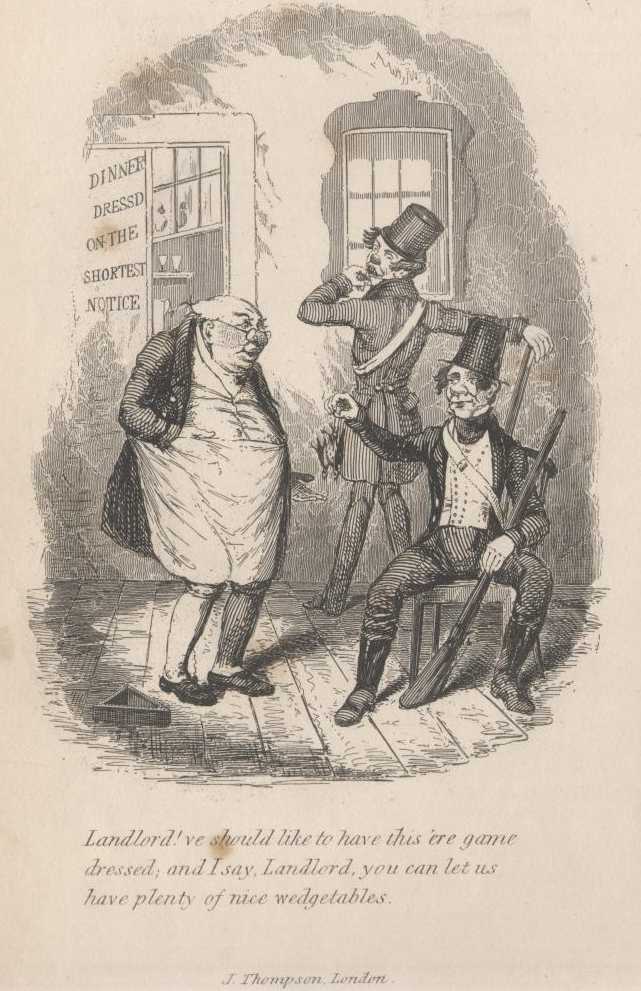

| CHAP. V. | A Publican taking Orders. |

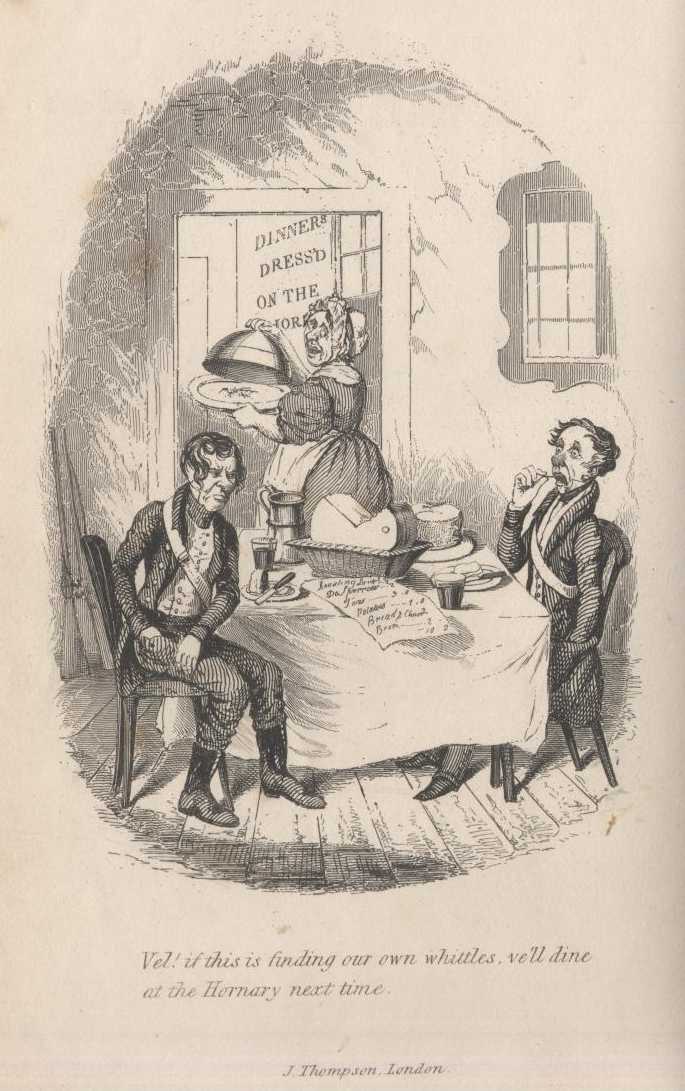

| CHAP. VI. | The Reckoning. |

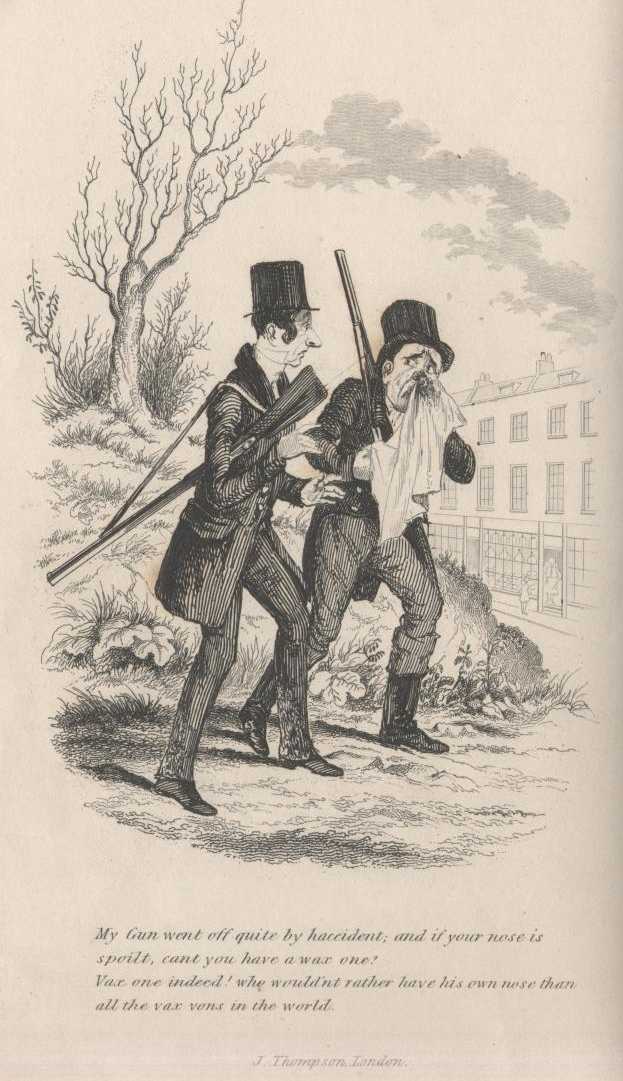

| CHAP. VII. | A sudden Explosion |

"Walked twenty miles over night: up before peep o' day again got a capital place; fell fast asleep; tide rose up to my knees; my hat was changed, my pockets picked, and a fish ran away with my hook; dreamt of being on a Polar expedition and having my toes frozen."

O! IZAAK WALTON!—Izaak Walton!—you have truly got me into a precious line, and I certainly deserve the rod for having, like a gudgeon, so greedily devoured the delusive bait, which you, so temptingly, threw out to catch the eye of my piscatorial inclination! I have read of right angles and obtuse angles, and, verily, begin to believe that there are also right anglers and obtuse anglers—and that I am really one of the latter class. But never more will I plant myself, like a weeping willow, upon the sedgy bank of stream or river. No!—on no account will I draw upon these banks again, with the melancholy prospect of no effects! The most 'capital place' will never tempt me to 'fish' again!

My best hat is gone: not the 'way of all beavers'—into the water—but to cover the cranium of the owner of this wretched 'tile;' and in vain shall I seek it; for 'this' and 'that' are now certainly as far as the 'poles' asunder.

My pockets, too, are picked! Yes—some clever 'artist' has drawn me while asleep!

My boots are filled with water, and my soles and heels are anything but lively or delighted. Never more will I impale ye, Gentles! on the word of a gentleman!—Henceforth, O! Hooks! I will be as dead to your attractions as if I were 'off the hooks!' and, in opposition to the maxim of Solomon, I will 'spare the rod.'

Instead of a basket of fish, lo! here's a pretty kettle of fish for the entertainment of my expectant friends—and sha'n't I be baited? as the hook said to the anger: and won't the club get up a Ballad on the occasion, and I, who have caught nothing, shall probably be made the subject of a 'catch!'

Slush! slush!—Squash! squash!

O! for a clean pair of stockings!—But, alack, what a tantalizing

situation I am in!—There are osiers enough in the vicinity, but no hose

to be had for love or money!

A lark—early in the morning.

Two youths—and two guns appeared at early dawn in the suburbs. The youths were loaded with shooting paraphernalia and provisions, and their guns with the best Dartford gunpowder—they were also well primed for sport—and as polished as their gunbarrels, and both could boast a good 'stock' of impudence.

"Surely I heard the notes of a bird," cried one, looking up and down the street; "there it is again, by jingo!"

"It's a lark, I declare," asserted his brother sportsman.

"Lark or canary, it will be a lark if we can bring it down," replied his companion.

"Yonder it is, in that ere cage agin the wall."

"What a shame!" exclaimed the philanthropic youth,—"to imprison a warbler of the woodlands in a cage, is the very height of cruelty—liberty is the birthright of every Briton, and British bird! I would rather be shot than be confined all my life in such a narrow prison. What a mockery too is that piece of green turf, no bigger than a slop-basin. How it must aggravate the feelings of one accustomed to range the meadows."

"Miserable! I was once in a cage myself," said his chum.

"And what did they take you for?"

"Take me for?—for a 'lark.'"

"Pretty Dickey!"

"Yes, I assure you, it was all 'dickey' with me."

"And did you sing?"

"Didn't I? yes, i' faith I sang pretty small the next morning when they fined me, and let me out. An idea strikes me Suppose you climb up that post, and let out this poor bird, ey?"

"Excellent."

"And as you let him off, I'll let off my gun, and we'll see whether I can't 'bang' him in the race."

No sooner said than done: the post was quickly climbed—the door of the cage was thrown open, and the poor bird in an attempt at 'death or liberty,' met with the former.

Bang went the piece, and as soon as the curling smoke was dissipated, they sought for their prize, but in vain; the piece was discharged so close to the lark, that it was blown to atoms, and the feathers strewed the pavement.

"Bolt!" cried the freedom-giving youth, "or we shall have to pay for the lark."

"Very likely," replied the other, who had just picked up a few feathers,

and a portion of the dissipated 'lark,'—"for look, if here ain't

the—bill, never trust me."

"You shall have the paper directly, Sir, but really the debates are so very interesting."

"Oh! pray don't hurry, Sir, it's only the scientific notices I care about."

WHAT a thrill of pleasure pervades the philanthropic breast on beholding the rapid march of Intellect! The lamp-lighter, but an insignificant 'link' in the vast chain of society, has now a chance of shining at the Mechanics', and may probably be the means of illuminating a whole parish.

Literature has become the favourite pursuit of all classes, and the postman is probably the only man who leaves letters for the vulgar pursuit of lucre! Even the vanity of servant-maids has undergone a change—they now study 'Cocker' and neglect their 'figures.'

But the dustman may be said, 'par excellence,' to bear—the bell!

In the retired nook of an obscure coffee-shop may frequently be observed a pair of these interesting individuals sipping their mocha, newspaper in hand, as fixed upon a column—as the statue of Napoleon in the Place Vendome, and watching the progress of the parliamentary bills, with as much interest as the farmer does the crows in his corn-field!

They talk of 'Peel,' and 'Hume,' and 'Stanley,' and bandy about their names as familiarly as if they were their particular acquaintances.

"What a dust the Irish Member kicked up in the House last night," remarks one.

"His speech was a heap o' rubbish," replied the other.

"And I've no doubt was all contracted for! For my part I was once a Reformer—but Rads and Whigs is so low, that I've turned Conservative."

"And so am I, for my Sal says as how it's so genteel!"

"Them other chaps after all on'y wants to throw dust in our eyes! But it's no go, they're no better than a parcel o' thimble riggers just making the pea come under what thimble they like,—and it's 'there it is,' and 'there it ain't,'—just as they please—making black white, and white black, just as suits 'em—but the liberty of the press—"

"What's the liberty of the press?"

"Why calling people what thinks different from 'em all sorts o' names—arn't that a liberty?"

"Ay, to be sure!—but it's time to cut—so down with the dust—and let's

bolt!"

"Oh! Sally, I told my missus vot you said your missus said about her."—

"Oh! and so did I, Betty; I told my missus vot you said yourn said of her, and ve had sich a row!"

SALLY. OH! Betty, ve had sich a row!—there vas never nothink like it;— I'm quite a martyr. To missus's pranks; for, 'twixt you and me, she's a bit of a tartar. I told her vord for vord everythink as you said, And I thought the poor voman vould ha' gone clean out of her head!

BETTY. Talk o' your missus! she's nothink to mine,—I on'y hope they von't meet, Or I'm conwinced they vill go to pulling of caps in the street: Sich kicking and skrieking there vas, as you never seed, And she vos so historical, it made my wery heart bleed.

SALLY. Dear me! vell, its partic'lar strange people gives themselves sich airs, And troubles themselves so much 'bout other people's affairs; For my part, I can't guess, if I died this werry minute, Vot's the use o' this fuss—I can't see no reason in it.

BETTY. Missus says as how she's too orrystocratic to mind wulgar people's tattle, And looks upon some people as little better nor cattle.

SALLY. And my missus says no vonder, as yourn can sport sich a dress, For ven some people's husbands is vite-vashed, their purses ain't less; This I will say, thof she puts herself in wiolent rages, She's not at all stingy in respect of her sarvant's wages.

BETTY. Ah! you've got the luck of it—for my missus is as mean as she's proud; On'y eight pound a-year, and no tea and sugar allowed. And then there's seven children to do for—two is down with the measles, And t'others, poor things! is half starved, and as thin as weazles; And then missus sells all the kitchen stuff!—(you don't know my trials!) And takes all the money I get at the rag-shop for the vials!

SALLY. Vell! I could'nt stand that!—If I was you, I'd soon give her warning.

BETTY.

She's saved me the trouble, by giving me notice this morning. But—hush!

I hear master bawling out for his shaving water—

Jist tell your missus from me, mine's everythink as she thought her!

"How does it fit behind? O! beautful; I've done wonders—we'll never trouble the tailors again, I promise them."

IT is the proud boast of some men that they have 'got a wrinkle.' How elated then ought this individual to be who has got so many! and yet, judging from the fretful expression of his physiognomy, one would suppose that he is by no means in 'fit' of good humour.

His industrious rib, however, appears quite delighted with her handiwork, and in no humour to find the least fault with the loose habits of her husband. He certainly looks angry, as a man naturally will when his 'collar' is up.

She, on the other hand, preserves her equanimity in spite of his unexpected frowns, knowing from experience that those who sow do not always reap; and she has reason to be gratified, for every beholder will agree in her firm opinion, that even that inimitable ninth of ninths—Stulz, never made such a coat!

In point of economy, we must allow some objections may be made to the extravagant waist, while the cuffs she has bestowed on him may probably be a fair return (with interest) of buffets formerly received.

The tail (in two parts) is really as amusing as any 'tale' that ever emanated from a female hand. There is a moral melancholy about it that is inexpressibly interesting, like two lovers intended for each other, and that some untoward circumstance has separated; they are 'parted,' and yet are still 'attached,' and it is evident that one seems 'too long' for the other.

The 'goose' generally finishes the labours of the tailor. Now, some carping critics may be wicked enough to insinuate that this garb too was finished by a goose! The worst fate I can wish to such malignant scoffers is a complete dressing from this worthy dame; and if she does not make the wisest of them look ridiculous, then, and not till then, will I abjure my faith in her art of cutting!

And proud ought that man to be of such a wife; for never was mortal

'suited' so before!

"Catching—a cold."

WHAT a type of true philosophy and courage is this Waltonian!

Cool and unmoved he receives the sharp blows of the blustering wind—as if he were playing dummy to an experienced pugilist.

Although he would undoubtedly prefer the blast with the chill off, he is so warm an enthusiast, in the pursuit of his sport, that he looks with contempt upon the rude and vulgar sport of the elements. He really angles for love—and love alone—and limbs and body are literally transformed to a series of angles!

Bent and sharp as his own hook, he watches his smooth float in the rough, but finds, alas! that it dances to no tune.

Time and bait are both lost in the vain attempt: patiently he rebaits,

until he finds the rebait brings his box of gentles to a discount; and

then, in no gentle humour, with a baitless hook, and abated ardor, he

winds up his line and his day's amusement(?)—and departs, with the

determination of trying fortune (who has tried him) on some, future and

more propitious day. Probably, on the next occasion, he may be gratified

with the sight of, at least, one gudgeon, should the surface of the river

prove glassy smooth and mirror-like. (We are sure his self-love will not

be offended at the reflection!) and even now he may, with truth, aver,

that although he caught nothing, he, at least, took the best perch in the

undulating stream!

"Help! help! Oh! you murderous little villin? this is vot you calls rowing, is it?—but if ever I gets safe on land again, I'll make you repent it, you rascal. I'll row you—that I will."

"MISTER Vaterman, vot's your fare for taking me across?"

"Across, young 'ooman? vy, you looks so good-tempered, I'll pull you over for sixpence?"

"Are them seats clean?"

"O! ker-vite:—I've just swabb'd 'em down."

"And werry comfortable that'll be! vy, it'll vet my best silk?"

"Vatered silks is all the go. Vel! vell! if you don't like; it, there's my jacket. There, sit down a-top of it, and let me put my arm round you."

"Fellow!"

"The arm of my jacket I mean; there's no harm in that, you know."

"Is it quite safe? How the wind blows!"

"Lord! how timorsome you be! vy, the vind never did nothin' else since I know'd it"

"O! O! how it tumbles! dearee me!"

"Sit still! for ve are just now in the current, and if so be you go over here, it'll play old gooseberry with you, I tell you."

"Is it werry deep?"

"Deep as a lawyer."

"O! I really feel all over"—

"And, by Gog, you'll be all over presently—don't lay your hand on my scull"

"You villin, I never so much as touched your scull. You put me up."

"I must put you down. I tell you what it is, young 'ooman, if you vant to go on, you must sit still; if you keep moving, you'll stay where you are—that's all! There, by Gosh! we're in for it." At this point of the interesting dialogue, the young 'ooman gave a sudden lurch to larboard, and turned the boat completely over. The boatman, blowing like a porpoise, soon strode across the upturned bark, and turning round, beheld the drenched "fare" clinging to the stern.

"O! you partic'lar fool!" exclaimed the waterman. "Ay, hold on a-stern,

and the devil take the hindmost, say I!"

In for it, or Trying the middle.

|

A little fat man

With rod, basket, and can, And tackle complete, Selected a seat On the branch of a wide-spreading tree, That stretch'd over a branch of the Lea: There he silently sat, Watching his float—like a tortoise-shell cat, That hath scented a mouse, In the nook of a room in a plentiful house. But alack! He hadn't sat long—when a crack At his back Made him turn round and pale— And catch hold of his tail! But oh! 'twas in vain That he tried to regain The trunk of the treacherous tree; So he With a shake of his head Despairingly said— "In for it,—ecod!" And away went his rod, And his best beaver hat, Untiling his roof! But he cared not for that, For it happened to be a superb water proof, Which not being himself, The poor elf! Felt a world of alarm As the arm Most gracefully bow'd to the stream, As if a respect it would show it, Tho' so much below it! No presence of mind he dissembled, But as the branch shook so he trembled, And the case was no longer a riddle Or joke; For the branch snapp'd and broke; And altho' The angler cried "Its no go!" He was presently—'trying the middle.' |

The Invitation—the Outfit—and the sallying forth.

TO Mr. AUGUSTUS SPRIGGS,

AT Mr. WILLIAMS'S, GROCER, ADDLE STREET.

(Tower Street, 31st August, 18__)

My dear Chum,

Dobbs has give me a whole holiday, and it's my intention to take the field to-morrow—and if so be you can come over your governor, and cut the apron and sleeves for a day—why

"Together we will range the fields;"

and if we don't have some prime sport, my name's not Dick, that's all.

I've bought powder and shot, and my cousin which is Shopman to my Uncle at the corner, have lent me a couple of guns that has been 'popp'd.' Don't mind the expense, for I've shot enough for both. Let me know by Jim if you can cut your stick as early as nine, as I mean to have a lift by the Highgate what starts from the Bank.

Mind, I won't take no refusal—so pitch it strong to the old 'un, and carry your resolution nem. con.

And believe me to be, your old Crony,

RICHARD GRUBB.

P. S. The guns hasn't got them thingummy 'caps,' but that's no matter, for cousin says them cocks won't always fight: while them as he has lent is reg'lar good—and never misses fire nor fires amiss.

In reply to this elegant epistle, Mr. Richard Grubb was favoured with a line from Mr. Augustus Spriggs, expressive of his unbounded delight in having prevailed upon his governor to 'let him out;' and concluding with a promise of meeting the coach at Moorgate.

At the appointed hour, Mr. Richard Grubb, 'armed at all points,' mounted the stage—his hat cocked knowingly over his right eye—his gun half-cocked and slung over his shoulder, and a real penny Cuba in his mouth.

"A fine mornin' for sport," remarked Mr. Richard Grubb to his fellow-passenger, a stout gentleman between fifty and sixty years of age, with a choleric physiognomy and a fierce-looking pigtail.

"I dessay—"

"Do you hang out at Highgate?" continued the sportsman.

"Hang out?"

"Ay, are you a hinhabitant?"

"To be sure I am."

"Is there any birds thereabouts?"

"Plenty o' geese," sharply replied the old gentleman.

"Ha! ha! werry good!—but I means game;—partridges and them sort o' birds."

"I never see any except what I've brought down."

"I on'y vish I may bring down all I see, that's all," chuckled the joyous Mr. Grubb.

"What's the matter?"

"I don't at all like that 'ere gun."

"Lor! bless you, how timorsome you are, 'tain't loaded."

"Loaded or not loaded, it's werry unpleasant to ride with that gun o' yours looking into one's ear so."

"Vell, don't be afeard, I'll twist it over t'other shoulder,—there! but a gun ain't a coach, you know, vich goes off whether it's loaded or not. Hollo! Spriggs! here you are, my boy, lord! how you are figg'd out—didn't know you—jump up!"

"Vere's my instrument o' destruction?" enquired the lively Augustus, when he had succeeded in mounting to his seat.

"Stow'd him in the boot!"

The coachman mounted and drove off; the sportsmen chatting and laughing as they passed through 'merry Islington.'

"Von't ve keep the game alive!" exclaimed Spriggs, slapping his friend upon the back.

"I dessay you will," remarked the caustic old boy with the pigtail; "for it's little you'll kill, young gentlemen, and that's my belief!"

"On'y let's put 'em up, and see if we don't knock 'em down, as cleverly as Mister Robins does his lots," replied Spriggs, laughing at his own wit.

Arrived at Highgate, the old gentleman, with a step-fatherly anxiety, bade them take care of the 'spring-guns' in their perambulations.

"Thankee, old boy," said Spriggs, "but we ain't so green as not to

know that spring guns, like spring radishes, go off long afore Autumn,

you know!"

The Death of a little Pig, which proves a great Bore!

"Now let's load and prime—and make ready," said Mr. Richard, when they had entered an extensive meadow, "and—I say—vot are you about? Don't put the shot in afore the powder, you gaby!"

Having charged, they shouldered their pieces and waded through the tall grass.

"O! crikey!—there's a heap o' birds," exclaimed Spriggs, looking up at a flight of alarmed sparrows. "Shall I bring 'em down?"

"I vish you could! I'd have a shot at 'em," replied Mr. Grubb, "but they're too high for us, as the alderman said ven they brought him a couple o' partridges vot had been kept overlong!"

"My eye! if there ain't a summat a moving in that 'ere grass yonder—cock your eye!" "Cock your gun—and be quiet," said Mr. Grubb. The anxiety of the two sportsmen was immense. "It's an hare—depend on't—stoop down—pint your gun,—and when I say fire—fire! there it is—fire!"

Bang! bang! went the two guns, and a piercing squeak followed the report.

"Ve've tickled him," exclaimed Spriggs, as they ran to pick up the spoil.

"Ve've pickled him, rayther," cried Grubbs, "for by gosh it's a piggy!"

"Hallo! you chaps, vot are you arter?" inquired a man, popping his head over the intervening hedge. "Vy, I'm blessed if you ain't shot von o' Stubbs's pigs." And leaping the hedge he took the 'pork' in his arms, while the sportsmen who had used their arms so destructively now took to their legs for security. But ignorance of the locality led them into the midst of a village, and the stentorian shouts of the pig-bearer soon bringing a multitude at their heels, Mr. Richard Grubb was arrested in his flight. Seized fast by the collar, in the grasp of the butcher and constable of the place, all escape was vain. Spriggs kept a respectful distance.

"Now my fine fellow," cried he, brandishing his staff, "you 'ither pays for that 'ere pig, or ve'll fix you in the cage."

Now the said cage not being a bird-cage, Mr. Richard Grubb could see no prospect of sport in it, and therefore fearfully demanded the price of the sucking innocent, declaring his readiness to 'shell out.'

Mr. Stubbs, the owner, stepped forward, and valued it at eighteen shillings.

"Vot! eighteen shillings for that 'ere little pig!" exclaimed the astounded sportsman. "Vy I could buy it in town for seven any day."

But Mr. Stubbs was obdurate, and declared that he would not 'bate a farden,' and seeing no remedy, Mr. Richard Grubb was compelled to 'melt a sovereign,' complaining loudly of the difference between country-fed and town pork!

Shouldering his gun, he joined his companion in arms, amid the jibes and jeers of the grinning rustics.

"Vell, I'm blowed if that ain't a cooler!" said he.

"Never mind, ve've made a hit at any rate," said the consoling Spriggs, "and ve've tried our metal."

"Yes, it's tried my metal preciously—changed a suv'rin to two bob! by jingo!"

"Let's turn Jews," said Spriggs, "and make a vow never to touch pork again!"

"Vot's the use o' that?"

"Vy, we shall save our bacon in future, to be sure," replied Spriggs, laughing, and Grubb joining in his merriment, they began to look about them, not for fresh pork, but for fresh game.

"No more shooting in the grass, mind!" said Grubb, "or ve shall have

the blades upon us agin for another grunter p'r'aps. Our next haim must

be at birds on the ving! No more forking out. Shooting a pig ain't no

lark—that's poz!"

The Sportsmen trespass on an Enclosure—Grubb gets on a paling and runs a risk of being impaled.

"Twig them trees?"—said Grubb.

"Prime!" exclaimed Spriggs, "and vith their leaves ve'll have an hunt there.—Don't you hear the birds a crying 'sveet,' 'sveet?' Thof all birds belong to the Temperance Society by natur', everybody knows as they're partic'larly fond of a little s'rub!"

"Think ve could leap the ditch?" said Mr. Richard, regarding with a longing look the tall trees and the thick underwood.

"Lauk! I'll over it in a jiffy," replied the elastic Mr. Spriggs there ain't no obelisk a sportsman can't overcome"—and no sooner had be uttered these encouraging words, than he made a spring, and came 'close-legged' upon the opposite bank; unfortunately, however, he lost his balance, and fell plump upon a huge stinging nettle, which would have been a treat to any donkey in the kingdom!

"Oh!—cuss the thing!" shrieked Mr. Spriggs, losing his equanimity with his equilibrium.

"Don't be in a passion, Spriggs," said Grubb, laughing.

"Me in a passion?—I'm not in a passion—I'm on'y—on'y—nettled!" replied he, recovering his legs and his good humour. Mr. Grubb, taking warning by his friend's slip, cautiously looked out for a narrower part of the ditch, and executed the saltatory transit with all the agility of a poodle.

They soon penetrated the thicket, and a bird hopped so near them, that they could not avoid hitting it.—Grubb fired, and Sprigg's gun echoed the report.

"Ve've done him!" cried Spriggs.

"Ve!—me, if you please."

"Vell—no matter," replied his chum, "you shot a bird, and I shot too!—Vot's that?—my heye, I hear a voice a hollering like winkin; bolt!"

Away scampered Spriggs, and off ran Grubb, never stopping till he reached a high paling, which, hastily climbing, he found himself literally upon tenter-hooks.

"There's a man a coming, old fellow," said an urchin, grinning.

"A man coming! vich vay? do tell me vich vay?" supplicated the sportsman. The little rogue, however, only stuck his thumb against his snub nose—winked, and ran off.

But Mr. Grubb was not long held in suspense; a volley of inelegant phrases saluted his ears, while the thong of a hunting-whip twisted playfully about his leg. Finding the play unequal, he wisely gave up the game—by dropping his bird on one side, and himself on the other; at the same time reluctantly leaving a portion of his nether garment behind him.

"Here you are!" cried his affectionate friend,—picking him up—"ain't you cotch'd it finely?"

"Ain't I, that's all?" said the almost breathless Mr. Grubb, "I'm almost dead."

"Dead!—nonsense—to be sure, you may say as how you're off the hooks! and precious glad you ought to be."

"Gracious me! Spriggs, don't joke; it might ha' bin werry serious," said Mr. Grubb, with a most melancholy shake of the head:—"Do let's get out o' this wile place."

"Vy, vat the dickins!" exclaimed Spriggs, "you ain't sewed up yet, are you?"

"No," replied Grubb, forcing a smile in spite of himself, "I vish I vos, Spriggs; for I 've got a terrible rent here!" delicately indicating the position of the fracture.

And hereupon the two friends resolving to make no further attempt at

bush-ranging, made as precipitate a retreat as the tangled nature of the

preserve permitted.

Shooting a Bird, and putting Shot into a Calf!

"ON'Y think ven ve thought o' getting into a preserve—that ve got into a pickle," said Sprigg, still chuckling over their last adventure.

"Hush!" cried Grubb, laying his hand upon his arm—"see that bird hopping there?"

"Ve'll soon make him hop the twig, and no mistake," remarked Spriggs.

"There he goes into the 'edge to get his dinner, I s'pose."

"Looking for a 'edge-stake, I dare say," said the facetious Spriggs.

"Now for it!" cried Grubb! "pitch into him!" and drawing his trigger he accidentally knocked off the bird, while Spriggs discharged the contents of his gun through the hedge.

"Hit summat at last!" exclaimed the delighted Grubb, scampering towards the thorny barrier, and clambering up, he peeped into an adjoining garden.

"Will you have the goodness to hand me that little bird I've just shot off your 'edge," said he to a gardener, who was leaning on his spade and holding his right leg in his hand.

"You fool," cried the horticulturist, "you've done a precious job— You've shot me right in the leg—O dear! O dear! how it pains!"

"I'm werry sorry—take the bird for your pains," replied Grubb, and apprehending another pig in a poke, he bobbed down and retreated as fast as his legs could carry him.

"Vot's frightened you?" demanded Spriggs, trotting off beside his chum, "You ain't done nothing, have you?"

"On'y shot a man, that's all."

"The devil!"

"It's true—and there'll be the devil to pay if ve're cotched, I can tell you—'Vy the gardener vill swear as it's a reg'lar plant!—and there von't be no damages at all, if so be he says he can't do no work, and is obleeged to keep his bed—so mizzle!" With the imaginary noises of a hot pursuit at their heels, they leaped hedge, ditch, and style without daring to cast a look behind them—and it was not until they had put two good miles of cultivated land between them and the spot of their unfortunate exploit that they ventured to wheel about and breathe again.

"Vell, if this 'ere ain't a rum go!"—said Spriggs—"in four shots—ve've killed a pig—knocked the life out o' one dicky-bird—and put a whole charge into a calf. Vy, if ve go on at this rate we shall certainly be taken up and get a setting down in the twinkling of a bed-post!"

"See if I haim at any think agin but vot's sitting on a rail or a post"—said Mr. Richard—"or s'pose Spriggs you goes on von side of an 'edge and me on t'other—and ve'll get the game between us—and then—"

"Thankye for me, Dick," interrupted Spriggs, "but that'll be a sort o' cross-fire that I sha'n't relish no how.—Vy it'll be just for all the world like fighting a jewel—on'y ve shall exchange shots—p'r'aps vithout any manner o' satisfaction to 'ither on' us. No—no—let's shoot beside von another—for if ve're beside ourselves ve may commit suicide."

"My vig!" cries Mr. Grubb, "there's a covey on 'em."

"Vere?"

"There!"

"Charge 'em, my lad."

"Stop! fust charge our pieces."

Having performed this preliminary act, the sportsmen crouched in a dry ditch and crawled stealthily along in order to approach the tempting covey as near as possible.

Up flew the birds, and with trembling hands they simultaneously touched the triggers.

"Ve've nicked some on 'em."

"Dead as nits," said Spriggs.

"Don't be in an hurry now," said the cautious Mr. Grubb, "ve don't know for certain yet, vot ve hav'n't hit."

"It can't be nothin' but a balloon then," replied Spriggs, "for ve on'y fired in the hair I'll take my 'davy."

Turning to the right and the left and observing nothing, they boldly advanced in order to appropriate the spoil.

"Here's feathers at any rate," said Spriggs, "ve've blown him to shivers, by jingo!"

"And here's a bird! hooray!" cried the delighted Grubb—"and look'ee, here's another—two whole 'uns—and all them remnants going for nothing as the linen-drapers has it!"

"Vot are they, Dick?" inquired Spriggs, whose ornithological knowledge was limited to domestic poultry; "sich voppers ain't robins or sparrers, I take it."

"Vy!" said the dubious Mr. Richard-resting on his gun and throwing one leg negligently over the other—"I do think they're plovers, or larks, or summat of that kind."

"Vot's in a name; the thing ve call a duck by any other name vould heat as vell!" declaimed Spriggs, parodying the immortal Shakspeare.

"Talking o' heating, Spriggs—I'm rayther peckish—my stomick's bin

a-crying cupboard for a hour past.—Let's look hout for a hinn!"

An extraordinary Occurrence—a Publican taking Orders.

TYING the legs of the birds together with a piece of string, Spriggs proudly carried them along, dangling at his fingers' ends.

After tramping for a long mile, the friends at length discovered, what they termed, an house of "hentertainment."

Entering a parlour, with a clean, sanded floor, (prettily herring-boned, as the housemaids technically phrase it,) furnished with red curtains, half a dozen beech chairs, three cast-iron spittoons, and a beer-bleached mahogany table,—Spriggs tugged at the bell. The host, with a rotund, smiling face, his nose, like Bardolph's, blazing with fiery meteors, and a short, white apron, concealing his unmentionables, quickly answered the tintinabulary summons.

"Landlord," said Spriggs, who had seated himself in a chair, while Mr. Richard was adjusting his starched collar at the window;—"Landlord! ve should like to have this 'ere game dressed."

The Landlord eyed the 'game' through his spectacles, and smiled.

"Roasted, or biled, Sir?" demanded he.

"Biled?—no:—roasted, to be sure!" replied Spriggs, amazed at his pretended obtuseness: "and, I say, landlord, you can let us have plenty o' nice wedgetables."

"Greens?" said the host;—but whether alluding to the verdant character of his guests, or merely making a polite inquiry as to the article they desired, it was impossible, from his tone and manner, to divine.

"Greens!" echoed Spriggs, indignantly; "no:—peas and 'taters."

"Directly, Sir," replied the landlord; and taking charge of the two leetle birds, he departed, to prepare them for the table.

"Vot a rum cove that 'ere is," said Grubb.

"Double stout, eh?" said Spriggs, and then they both fell to a-laughing; "and certain it is, that, although the artist has only given us a draught of the landlord, he was a subject sufficient for a butt!

"Vell! I must, say," said Grubb, stretching his weary legs under the mahogany, "I never did spend sich a pleasant day afore—never!"

"Nor I," chimed in Spriggs, "and many a day ven I'm a chopping up the 'lump' shall I think on it. It's ralely bin a hout and houter! Lauk! how Suke vill open her heyes, to be sure, ven I inform her how ve've bin out with two real guns, and kill'd our own dinner. I'm bless'd if she'll swallow it!"

"I must say ve have seen a little life," said Grubb.

"And death too," added Spriggs. "Vitness the pig!"

"Now don't!" remonstrated Grubb, who was rather sore upon this part of the morning's adventures.

"And the gardener,"—persisted Spriggs.

"Hush for goodness sake!" said Mr. Richard, very seriously, "for if that 'ere affair gets vind, ve shall be blown, and—"

—In came the dinner. The display was admirable and very abundant, and the keen air, added to the unusual exercise of the morning, had given the young gentlemen a most voracious appetite.

The birds were particularly sweet, but afforded little more than a mouthful to each.

The 'wedgetables,' however, with a due proportion of fine old Cheshire, and bread at discretion, filled up the gaps. It was only marvellous where two such slender striplings could find room to stow away such an alarming quantity.

How calm and pleasant was the 'dozy feel' that followed upon mastication, as they opened their chests (and, if there ever was a necessity for such an action, it was upon this occasion,) and lolling back in their chairs, sipped the 'genuine malt and hops,' and picked their teeth!

The talkative Spriggs became taciturn. His gallantry, however, did prompt him, upon the production of a 'fresh pot,' to say,

"Vell, Grubbs, my boy, here's the gals!"

"The gals!" languidly echoed Mr. Richard, tossing off his tumbler,

with a most appropriate smack.

The Reckoning.

"PULL the bell, Spriggs," said Mr. Richard, "and let's have the bill."

Mr. Augustus Spriggs obeyed, and the landlord appeared.

"Vot's to pay?"

"Send you the bill directly, gentlemen," replied the landlord, bowing, and trundling out of the room.

The cook presently entered, and laying the bill at Mr. Grubb's elbow, took off the remnants of the 'game,' and left the sportsmen to discuss the little account.

"My eye! if this ain't a rum un!" exclaimed Grubb, casting his dilating oculars over the slip.

"Vy, vot's the damage?" enquired Spriggs.

"Ten and fourpence."

"Ten and fourpence!—never!" cried his incredulous companion. "Vot a himposition."

"Vell!" said Mr. Grubb, with a bitter emphasis, "if this is finding our own wittles, we'll dine at the hor'nary next time"—

"Let's have a squint at it," said Mr. Spriggs, reaching across the table; but all his squinting made the bill no less, and he laid it down with a sigh. "It is coming it rayther strong, to be sure," continued he; "but I dare say it's all our happearance has as done it. He takes us for people o' consequence, and"—

"Vot consequence is that to us?" said Grubbs, doggedly.

"Vell, never mind, Dick, it's on'y vonce a-year, as the grotto-boys says—"

"It need'nt to be; or I'll be shot if he mightn't vistle for the brads. Howsomever, there's a hole in another suv'rin."

"Ve shall get through it the sooner," replied the consoling Spriggs. "I see, Grubb, there aint a bit of the Frenchman about you"—

"Vy, pray?"

"Cos, you know, they're fond o' changing their suv'rins, and—you aint!"

The pleasant humour of Spriggs soon infected Grubb, and he resolved to be jolly, and keep up the fun, in spite of the exorbitant charge for the vegetable addenda to their supply of game.

"Come, don't look at the bill no more," advised Spriggs, but treat it as old Villiams does his servants ven they displeases him."

"How's that?"

"Vy, discharge it, to be sure," replied he.

This sage advice being promptly followed, the sportsmen, shouldering their guns, departed in quest of amusement. They had not, however, proceeded far on their way, before a heavy shower compelled them to take shelter under a hedge.

"Werry pleasant!" remarked Spriggs.

"Keep your powder dry," said Grubb.

"Leave me alone," replied Spriggs; "and I think as we'd better pop our guns under our coat-tails too, for these ere cocks aint vater-cocks, you know! Vell, I never seed sich a rain. I'm bless'd if it vont drive all the dickey-birds to their nestes."

"I vish I'd brought a numberella," said Grubbs.

"Lank! vot a pretty fellow you are for a sportsman!" said Spriggs, "it don't damp my hardour in the least. All veathers comes alike to me, as the butcher said ven he vos a slaughtering the sheep!"

Mr. Richard Grubb, here joined in the laugh of his good-humoured friend, whose unwearied tongue kept him in spirits—rather mixed indeed than neat—for the rain now poured down in a perfect torrent.

"I say, Dick," said Spriggs, "vy are ve two like razors?"

"Cos ve're good-tempered?"

"Werry good; but that aint it exactly—cos ve're two bright blades, vot has got a beautiful edge!"

"A hexcellent conundrum," exclaimed Grubb. "Vere do you get 'em?'

"All made out of my own head,—as the boy said ven be showed the

wooden top-spoon to his father!"

A sudden Explosion—a hit by one of the Sportsmen, which the other takes amiss.

A blustering wind arose, and like a burly coachman on mounting his box, took up the rain!

The two crouching friends taking advantage of the cessation in the storm, prepared to start. But in straightening the acute angles of their legs and arms, Mr. Sprigg's piece, by some entanglement in his protecting garb, went off, and the barrel striking Mr. Grubb upon the os nasi, stretched him bawling on the humid turf.

"O! Lord! I'm shot."

"O! my heye!" exclaimed the trembling Spriggs.

"O! my nose!" roared Grubb.

"Here's a go!"

"It's no go!—I'm a dead man!" blubbered Mr. Richard. Mr. Augustus Spriggs now raised his chum upon his legs, and was certainly rather alarmed at the sanguinary effusion.

"Vere's your hankercher?—here!—take mine,—that's it—there!—let's look at it."

"Can you see it?" said Grubb, mournfully twisting about his face most ludicrously, and trying at the same time to level his optics towards the damaged gnomon.

"Yes!"

"I can't feel it," said Grubb; "it's numbed like dead."

"My gun vent off quite by haccident, and if your nose is spoilt, can't you have a vax von?—Come, it ain't so bad!"

"A vax von, indeed!—who vouldn't rather have his own nose than all the vax vons in the vorld?" replied poor Richard. "I shall never be able to show my face."

"Vy not?—your face ain't touched, it's on'y your nose!"

"See, if I come out agin in an hurry," continued the wounded sportsman. "I've paid precious dear for a day's fun. The birds vill die a nat'ral death for me, I can tell you."

"It vos a terrible blow—certainly," said Spriggs; "but these things vill happen in the best riggle'ated families!"

"How can that be? there's no piece, in no quiet and respectable families as I ever seed!"

And with this very paradoxical dictum, Mr. Grubb trudged on, leading himself by the nose; Spriggs exerting all his eloquence to make him think lightly of what Grubb considered such a heavy affliction; for after all, although he had received a terrible contusion, there were no bones broken: of which Spriggs assured his friend and himself with a great deal of feeling!

Luckily the shades of evening concealed them from the too scrutinizing observation of the passengers they encountered on their return, for such accidents generally excite more ridicule than commiseration.

Spriggs having volunteered his services, saw Grubb safe home to his door in Tower Street, and placing the two guns in his hands, bade him a cordial farewell, promising to call and see after his nose on the morrow.

The following parody of a customary paragraph in the papers will be considered, we think, a most fitting conclusion to their day's sport.

"In consequence of a letter addressed to Mr. Augustus Spriggs, by Mr.

Richard Grubb, the parties met early yesterday morning, but after firing

several shots, we are sorry to state that they parted without coming to

any satisfactory conclusion."

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of The Sketches of Seymour (Illustrated),

Part 1., by Robert Seymour

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SKETCHES OF SEYMOUR ***

***** This file should be named 5645-h.htm or 5645-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.net/5/6/4/5645/

Produced by David Widger

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://gutenberg.net/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.net),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH F3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need, is critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation web page at http://www.pglaf.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Its 501(c)(3) letter is posted at

http://pglaf.org/fundraising. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at

809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email

business@pglaf.org. Email contact links and up to date contact

information can be found at the Foundation's web site and official

page at http://pglaf.org

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit http://pglaf.org

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including including checks, online payments and credit card

donations. To donate, please visit: http://pglaf.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart is the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For thirty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

http://www.gutenberg.net

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.