The Project Gutenberg EBook of Hogarth's Works. Vol. 1 of 3, by

John Ireland and John Nichols

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Hogarth's Works. Vol. 1 of 3

With life and anecdotal descriptions of his pictures

Author: John Ireland

John Nichols

Release Date: April 29, 2016 [EBook #51821]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HOGARTH'S WORKS. VOL. 1 OF 3 ***

Produced by Chris Curnow, John Campbell and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE

Obvious typographical errors and punctuation errors have been corrected after careful comparison with other occurrences within the text and consultation of external sources.

Footnotes have been moved to the end of the book text, and before the publisher's Book Catalog. Some Footnotes are very long.

To avoid duplication, the page numbering in the publisher's Book Catalog at the back of the book has a suffix C added, so that for example page [23] in the Catalog is denoted as [23C].

The cover was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

More detail can be found at the end of the book.

HOGARTH'S WORKS:

WITH

LIFE AND ANECDOTAL DESCRIPTIONS OF HIS PICTURES.

BY

JOHN IRELAND and JOHN NICHOLS, F.S.A.

THE WHOLE OF THE PLATES REDUCED IN EXACT

FAC-SIMILE OF THE ORIGINALS.

First Series.

London

CHATTO AND WINDUS, PUBLISHERS.

(SUCCESSORS TO JOHN CAMDEN HOTTEN.)

DESCRIBED IN THE FIRST SERIES.

| PAGE | |

| Portrait of William Hogarth, with his dog Trump, | Frontispiece |

| Full-length Portrait of William Hogarth, by Himself, Engaged in Painting the Comic Muse, | 18 |

| The Battle of the Pictures, | 44 |

| Analysis of Beauty— | |

| Plate I., | 60 |

| Plate II., | 64 |

| Sigismunda, | 76 |

| Time Smoking a Picture, | 80 |

| The Harlot's Progress— | |

| Plate I. At the Bell Inn, in Wood Street—Mary Hackabout and the Procuress, | 102 |

| Plate II. The Jew's Mistress quarrelling with her Keeper, | 106 |

| Plate III. The Lodging in Drury Lane—Visit of the Constables, | 110 |

| Plate IV. Mary Hackabout beating Hemp in Bridewell, | 112 |

| Plate V. The Harlot's Death—Quacks Disputing, | 114 |

| Plate VI. The Funeral, | 118 |

| [6] The Rake's Progress— | |

| Plate I. Tom Rakewell taking possession of the rich Miser's effects, | 124 |

| Plate II. The young Squire's Levee, | 128 |

| Plate III. The Night House, | 132 |

| Plate IV. The Spendthrift arrested for Debt—Released by his forsaken Sweetheart, | 136 |

| Plate V. Marylebone Church—Rakewell married to a Shrew, | 140 |

| Plate VI. The Fire at the Gambling Hell, | 144 |

| Plate VII. The Fleet Prison, | 148 |

| Plate VIII. The Madhouse—The Faithful Friend, | 154 |

| Southwark Fair, | 162 |

| A Midnight Modern Conversation, | 184 |

| The Sleeping Congregation, | 192 |

| The Distressed Poet, | 200 |

| The Enraged Musician, | 206 |

| The Four Times of the Day— | |

| Morning. Miss Bridget Alworthy on her way to Church, | 216 |

| Noon. A Motley Congregation leaving Service, | 222 |

| Evening. The Shrew and her Husband going home—By the New River at Islington, | 226 |

| Night. The Drunken Freemason taken care of by the Waiter at the Rummer Tavern, | 230 |

| Strolling Actresses Dressing in a Barn, | 240 |

| Mr. Garrick in the Character of Richard the Third, | 255 |

| [7] Industry and Idleness— | |

| Plate I. The Fellow-apprentices, Thomas Goodchild and Thomas Idle, at their Looms, | 270 |

| Plate II. The Industrious Apprentice performing the duty of a Christian, | 272 |

| Plate III. The Idle Apprentice at play in the Churchyard during Divine Service, | 274 |

| Plate IV. The Industrious Apprentice a favourite, and trusted by his Master, | 276 |

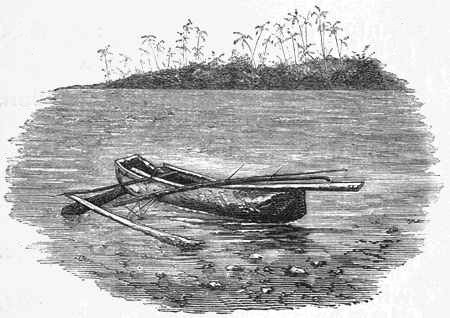

| Plate V. The Idle Apprentice turned away and sent to sea, | 278 |

| Plate VI. The Industrious Apprentice out of his time, and married to his Master's Daughter, | 280 |

| Plate VII. The Idle Apprentice returned from sea, and in a Garret with a Common Prostitute, | 282 |

| Plate VIII. The Industrious Apprentice grown rich, and Sheriff of London, | 284 |

| Plate IX. The Idle Apprentice betrayed by a Prostitute, and taken in a Night-cellar with his Accomplice, | 286 |

| Plate X. The Industrious Apprentice Alderman of London—The Idle one brought before him and impeached by his Accomplice, | 288 |

| Plate XI. The Idle Apprentice Executed at Tyburn, | 290 |

| Plate XII. The Industrious Apprentice Lord Mayor of London, | 292 |

| Roast Beef at the Gate of Calais, | 298 |

| The Country Inn Yard—Preparing to Start the Coach, | 306 |

It is a singular fact, that, notwithstanding the enormous popularity enjoyed by Hogarth in the minds of English people, no perfectly popular edition has been hitherto brought before the public. Were a foreigner to ask an ordinary Briton who was the most thoroughly national painter in the roll of English artists, the answer would be undoubtedly William Hogarth; but the chances are that our countryman would not have at command a tangible proof that his statement was correct. Such editions as have hitherto appeared have been either expensive or unsatisfactory,—even the handsome and costly volume by Nichols is far from complete. To sup[10]ply the want, the present issue has been projected. The illustrative text of Ireland—undoubtedly the best in existence—has been given in full, and is supplemented by addenda from the works of Nichols. The three volumes form certainly the most complete gallery of Hogarth's drawings yet given to the public. The rapid progress of science has provided means by which the pictures have been reduced from their original size to the compact form of this page; while, at the same time, the most perfect truthfulness has been preserved.

Hogarth is essentially English—brave, straight-forward, manly; never pandering to fashion or fancy. When he had to deal with sin and misery, he met them full in the face, bating no whit of their repulsiveness; and in all his works, wherever a moral is to be drawn, it is a noble and a healthy one. In his merry moods he is irresistibly comic; when he stands forward as a censor of morals, he is terrible in his truth; when he creates a character, it is always human and complete,—a true reflex of the age in which he lived. Times may change, and costumes, but humanity remains much the same.[11] Take any series of the splendid list, and the people who crowd the canvas live and move amongst us with different names and other attire. Such suggestive cognomens as Mary Hackabout are not in use; nor do procuresses haunt such localities as Wood Street in pursuit of their vile calling. The course of fashion, as of empire, has taken its way westward; but the whole story of the Harlot's Progress is as fresh and as applicable to a season in 1873 as it was a hundred and forty years before. Have we not Tom Rakewells in scores among us; and had Hogarth been living now, would he not have interpolated another picture of the degradation attained by the spendthrift when he enters the employment of the moneylender as a decoy to poor flies such as he was himself at the beginning of the chapter? The function of the satirist is still needed, and there is no danger of the works of William Hogarth proving to be out of date. Probably no artist ever told stories so well; certainly no one ever acquired such a reputation, and there is no reason why his splendid monuments should be found only in the libraries of the wealthy. Every one should know something[12] of him besides his moral lessons, since, of all the moral lessons he ever taught, his life formed the most pointed. Fearlessness and honesty were his watchwords from his early career of art, after being released from the silversmith's apprenticeship in 1720 until the day of his death in 1764, when he retired from mundane existence full of years and honours. As Ireland declares him to have asserted, his drawings were meant for the crowd rather than for the critics; and with that intention his book was commenced, the original design being to comprise in one volume "a moral and analytical description of seventy-eight prints;" but as the work advanced, such an amount of anecdote and illustrative comment suggested itself, that he was compelled to adopt the three-volume form which is here followed, with the further addition to which we have alluded, of such a full description and reproduction as the original compiler, from accident or design, omitted. These will be found in the third volume, and include many of the most important and meritorious works of the great artist. It has been found advisable to change the ornamental and sometimes indistinct lettering[13] of the original plates, and to adopt a consistent and uniform style of titles. At the same time the elaborate catalogue compiled by Ireland is preserved, since it is still highly valuable as a chronological list of every effort of Hogarth's hand, although it would be folly to attempt a reproduction of every variation it contains. The system pursued by Ireland and Nichols is followed, and the Publishers venture to congratulate themselves on submitting to the notice of the artistic and literary world, as well as to the public generally, the best and cheapest edition of Hogarth's complete works ever brought forward.

Mr. Hogarth frequently asserted that no man was so ill qualified to form a true judgment of pictures as the professed connoisseur; whose taste being originally formed upon imitations, and confined to the manners of Masters, had seldom any reference to Nature. Under this conviction, his subjects were selected for the crowd rather than the critic;[1] and explained in that universal language common to the world, rather than in the lingua technica of the arts, which is sacred to the scientific. Without presuming to support his hypothesis, I have endeavoured to follow his example.

My original design was to have comprised in one volume a moral and analytical description of seventy-eight prints; but as the work advanced, such variety of anecdote and long train of et cetera clung to the narrative, that these limits were found too narrow. With the explanation of fifteen additional plates, the letterpress has expanded to near seven hundred pages.

Where the artist has been made a victim to poetical or political prejudice, without meaning to be his panegyrist, I have endeavoured to rescue his memory from unmerited obloquy. Where his works have been misconceived or misrepresented, I have attempted the true reading. In my essay at an illustration of the prints, with a description of what I conceive the comic and moral tendency of each, there is the best information I could procure concerning the relative circumstances, occasionally interspersed with such desultory conversation as frequently occurred in turning over a volume of his prints. Though the notes may not always have an immediate relation to the engravings, I hope they will seldom be found wholly unconnected with the subjects.

Such mottoes as were engraven on the plates are inserted; but where a print has been published without any inscription, I have either selected or written one. Errors in either parody or verse with the signature E, being written by the editor, are submitted to that tribunal from whose candour he hopes pardon for every mistake or inaccuracy which may be found in these volumes.

"By heaven, and not a master, taught."

When Leonardo da Vinci lay upon his death-bed, Francis the First, actuated by that instinctive reverence which great minds invariably feel for each other, visited him in his chamber. An attendant informing the painter that the king was come to inquire after his health, he raised himself from the pillow, a lambent gleam of gratitude for the honour lighted up his eyes, and he made an effort to speak. The exertion was too much; he fell back; and Francis stooping to support him, this great artist expired in his arms. Affected with the awful catastrophe, the king heaved a sigh of sympathetic sorrow, and left the bed-chamber in tears. He was immediately surrounded by a crowd of those kind-hearted nobles who delight in soothing the sorrows of a sovereign; and one of them entreating him not to indulge his grief, added, as a consolatory reflection, "Consider, sire, this man[18] was but a painter." "I do," replied the monarch; "and I at the same time consider, that though, as a king, I could make a thousand such as you, the Deity alone can make such a painter as Leonardo da Vinci."

Shall I be permitted to adopt this remark, and, without any diminution of the Italian's well-earned fame, assert that the eulogy is equally appropriate to the Englishman whose name is at the head of this chapter; for he was not the follower, but the leader of a class, and became a painter from divine impulse rather than human instruction.

The biographers who have written of artists, especially if the hero of their history was of the Dutch school, generally began by informing us that he received the rudiments of his art from the great Van A—, who was a pupil of the divine Van B—, first the disciple, and afterwards the rival, of the immortal and never enough to be admired Vander C.

This palette pedigree was not the boast of William Hogarth; he was the pupil,—the disciple,—the worshipper of nature!

I do not learn that his family either obtained a grant of lands from our first William, or flourished before the Conquest; but from Burn's History of Westmoreland, it appears that his grandfather was an honest yeoman, the inhabitant of a small tenement in the vale of Bampton, a village fifteen miles north of Kendal, and had three sons. The eldest, in conformity[19] to ancient custom, succeeded to the title, honour, and estate of his father, became a yeoman of Bampton, and proprietor of the family freehold.

The second was not endowed with either land or beeves, but had in their stead a large portion of broad humour and wild original genius. Like his nephew, he grasped the whip of satire; and though his lash was not twisted with much skill, nor brandished with much grace, it was probably felt by those on whom his strokes were inflicted, more than would one of the most exquisite workmanship.

He was the Shakspeare of his village, and his dramas were the delight of the country; though, being written by an uneducated yeoman, it may naturally be supposed they were sufficiently coarse. Mr. Nichols, in his Anecdotes, tells us that he has seen a whole bundle of them, and want of grammar, metre, sense, and decency is their invariable characteristic. This may possibly be true, for in refinement Westmoreland was many, many years behind the capital; and our libraries contain sundrie black-letter proofs that those pithie, pleasaunte, and merrie comedies, which in the same century were enacted by the Kingis servantes with universal applause, had similar wants; notwithstanding which, these unalloyed chronicles of our ancestors' dulness are now purchased at a price considerably higher than virgin gold. Let it not from hence be imagined that I[20] mean to sanction one folly by the mention of another; but as every human production is relative, if auld Hogarth, under the circumstances he wrote, was the admiration of his neighbours, we may fairly infer that his talents, properly cultivated, would, in a more polished situation, have ensured him the admiration of his contemporaries.[2]

Richard was the third son, and seems to have been intended for a scholar,—the scholar of his family!—for he was educated at St. Bees, in Westmoreland, and afterward kept a school in the same county. Of learning he had a portion more than sufficient for his office, for he wrote a Latin and English dictionary, which still exists in MS., and one of his Latin letters,[22] dated 1657, preserved in the British Museum. However well he might be qualified for a teacher, he had few pupils; and finding that his employment produced neither honour nor profit, removed to London, and in Ship Court, Old Bailey, renewed his profession.

It was fortunate for literature that Doctor Samuel Johnson was not successful in an application for the place of a provincial schoolmaster. It was fortunate for the arts that Richard Hogarth was not able to establish a village school, in which situation he would probably have qualified his son William for his successor; and those talents which were calculated to instruct, astonish, and reform a world, might have been wasted in teaching some half a hundred of the young Westmoreland gentry to scan verses by their fingers, and call English things by Latin names. The fates ordained otherwise; it was his destiny to marry and reside in London, where were born unto him one son and two daughters.

The girls had such instructions as qualified them to keep a shop; and the son, who drew his first breath in this bustling world in the year 1697, was author of the prints which, copied in little, form the basis and give the value to these volumes.

Of his education we do not know much; but as his father appears to have been a man of understanding, I suppose it was sufficient for the situation in which he was intended to be placed. That it was not more liberal, might arise from the old man finding erudition answer little purpose to himself, and knowing that in a mechanic employment it is rather a drawback than an assistance. Added to this, I believe young Hogarth had not much bias towards what has obtained the[24] name of learning. He must have been early attentive to the appearance of the passions, and feeling a strong impulse to attempt their delineation, left their names and derivations to the profound pedagogue, the accurate grammarian, or more sage and solemn lexicographer. While these labourers in the forest of science dug for the root, inquired into the circulation of the sap, and planted brambles and birch round the tree of knowledge, Hogarth had an higher aim,—an ambition to display, in the true tints of nature, the rugged character of the bark, the varied involutions of the branches, and the minute fibres of the leaves.

The first notices of his prints were written in French, by a Swiss named Rouquet, who in 1746 published "Lettres de Monsieur * * à un de ses Amis à Paris, pour lui expliquer les Estampes de Monsieur Hogarth."[3] This pamphlet describes the Harlot's and Rake's Progress, Marriage à la Mode, and March to Finchley. In the remarks, there is great reason to believe Rouquet was assisted by Hogarth, who long afterwards expressed an intention of having them translated and amplified. From such a junction, the reader will naturally expect this book to contain more information than he will find.

The second publication was by the Reverend Doctor Trusler, and extends farther than the preceding.[25] It was begun immediately after the artist's death, is baptized Hogarth Moralized, and interspersed with seventy-eight engravings, printed on the same paper with the letterpress. It contains two hundred pages, built upon Rouquet's pamphlet, and the information he received from Mrs. Hogarth, who, conceiving her property would be essentially injured by such a publication, purchased the copyright. As the Doctor does not profess an intimate acquaintance with the arts, and confines himself to morality!—I hope and believe my work will not much clash with his.

Of the artist and his prints, we had no regular narrative until the appearance of Mr. Walpole's Anecdotes of Painting,—a work in which refined taste and elegant diction gave rank and importance to a class of men whose history, in the writings of preceding biographers, exhibited little more than a catalogue of names, or a dry uninteresting narrative of uninteresting events. To the pen of this highly accomplished writer, William Hogarth owes a portion of his deserved celebrity; for in near fifty pages devoted to his name, we find the history of a great man's excellencies and errors written with the warmth of a friend and the fidelity of a chronologist. With the first tolerably complete catalogue of his works, there was such remarks upon their meaning and tendency, as have given the artist a new character; for though his superlative merit secured him admiration from the[26] few who were able to judge, he was considered by the crowd as a mere caricaturist, whose only aim was to burlesque whatever he represented.

The Reverend Mr. Gilpin, in his valuable Essay on Prints, has made some observations on one series by Hogarth. The remarks were evidently written in haste; and though in a few instances I cannot coincide with a gentleman for whose worth and talents I have the most unfeigned respect, I am convinced that the candour of the Vicar of Boldre will forgive the freedom taken with the critic on the Rake's Progress.

In 1781, Mr. Nichols published his Anecdotes, which since that time have been considerably enlarged. This work contains much useful information relative to the artist; and much monumental miscellany from the Grub Street Journal, and other ancient sources, concerning his contemporaries, that were it not there enniched, would in all probability have sunk in dark and endless night. Where Mr. Walpole and preceding writers threw a hair-line, he cast the antiquarian drag-net, and brought from the great deep a miraculous draught of aquatic monsters and web-footed animals, that swam round the triumphal bark of William Hogarth. For the information which I received from his volume, he has my best thanks; where I depart from his authorities, it is on the presumption that my own are better. In many cases, it is more than possible both of us are frequently mistaken.

In this I believe we agree,—that young Hogarth had an early predilection for the arts, and his future acquirements give us a right to suppose he must have studied the curious sculptures which adorned his father's spelling books, though he neglected the letterpress; and when he ought to have been storing his memory with the eight parts of speech, was examining the allegorical apple-tree which decorates the grammar. These first lines of nature inclined his father to place him with an engraver; but workers in copper were not numerous, neither did the demand for English prints warrant a certainty of any additional number obtaining constant employment. Engraving on plate seemed likely to afford a more permanent subsistence, required some taste for drawing, and had a remote alliance with the arts. These reasons being seconded by his own inclination, our juvenile satirist was apprenticed to Mr. Ellis Gamble, who kept a silversmith's shop in Cranbourn Alley, Leicester Fields. This vendor of salvers and sauce-boats had in his own house two or three rare artisans, whose employment was to engrave cyphers and armorial symbols, not only on the articles their master sold, but on any that he might have to mark from cunning workmen, in silver or meaner metals. In this branch he covenanted to instruct William Hogarth, who about the year 1712 became a practical student in Mr. Gamble's Attic Academy. In this[28] school of science, we may fairly conjecture his first essays were the initials on tea-spoons; he would next be taught the art and mystery of the double cypher, where four letters in opposite directions are so skilfully interwoven, that it requires almost an apprenticeship to learn the art of deciphering them. Having conquered his alphabet, he ascended to the representation of those heraldic monsters which first grinned upon the shields of the holy army of crusaders, and were from thence transferred to the massy tankards and ponderous two-handled cups of their stately descendants. By copying this legion of hydras, gorgons, and chimeras dire, he attained an early taste for the ridiculous; and in the grotesque countenance of a baboon or a bear, the cunning eye of a fox, or the fierce front of a rampant lion, traced the characteristic varieties of the human physiognomy. He soon felt that the science which appertaineth unto the bearing of coat armour was not suited to his taste or talents; and tired of the amphibious many-coloured brood that people the fields of heraldry, listened to the voice of Genius, which whispered him to read the mind's construction in the face,—to study and delineate MAN.

As the first token of his turn for the satirical, it may be worth recording, that while yet an apprentice, when upon a sultry Sunday he once made an excursion to Highgate, two or three of his companions and[29] himself sought shelter and refreshment in one of those convenient caravanserais which so much abound in the vicinity of the metropolis. In the same room were a party of thirsty pedestrians, washing down the dust they had inhaled in their walk, with London porter. Two of the company debating upon politics, and the palm of victory being, at the moment Hogarth and his companions entered, adjudged to the taller man, he very vociferously exulted in his conquest, and added some sarcastic remarks on the diminutive appearance of his adversary. The little man had a great soul, and having in his right hand a pewter pot, threw it with fatal force at his opponent: it struck him in the forehead,—and

"As the mountain oak

Nods to the axe, till with a groaning sound

It sinks, and spreads its honours on the ground,"—

he sunk to the floor, and there,—as the divine Ossian would have sublimely expressed it,—The grey mist swam before his eyes. He lay in the hall of mirth as a mountain pine, when it tumbles across the rushy Loda.—He recovered; lifted up his bleeding head, and rolled his full-orbed eyes around. He ascended as a pillar of smoke streaked with fire, and streams of blood ran down his dark brown cheeks, like torrents from the summit of an oozy rock, etc. etc.

To descend from the pinnacle of Parnassus to the plain of common sense,—the fellow being deeply,[30] though not dangerously, wounded in the forehead, extreme agony excited a most hideous grin. His woe-begone figure, opposed to the pert triumphant air of his tiny conqueror, and the half suppressed laugh of his surrounding friends, presented a scene too ridiculous to be resisted. The young tyro seized his pencil, drew his first group of portraits from the life, and gave, with a strong resemblance of each, such a grotesque variety of character as evades all description.

When we consider this little sketch was his coup d'essai, the loss of it is much to be regretted.

He probably made many others during his apprenticeship. When that expired, bidding adieu to red lions and green dragons, he endeavoured to attain such knowledge of drawing as would enable him to delineate the human figure, and transfer his burin from silver to copperplate. In this attempt he had to encounter many difficulties; engraving on copper was so different an art from engraving on silver, that it was necessary he should unlearn much which he had already learned; and at twenty years of age, habits are too deeply rooted to be easily eradicated; so that he never attained the power of describing that clear, beautiful stroke which was then given by some foreign artists, and has since been brought, I believe, to its utmost perfection by Sir Robert Strange.

In his first efforts he had little more assistance than[31] could be acquired by casual communications, or imitating the works of others;[4] those of Callot were probably his first models; and shop-bills and book-plates his first performances. Some of these, with impressions from tankards and tea-tables which escaped the crucible, have, by the laudable industry of collectors, been preserved to the present day. How far they add to the artist's fame, or are really of the value at which they are sometimes purchased, is a question of too high import for me to decide. By the connoisseur it is asserted, that the earliest productions of a great painter ought to be preserved, for they soar superior to the mature labours of plodding dulness, and though but seeds of that genius intended by nature to tower above its contemporaries, invariably exhibit clear marks of mind; as every variety in the branches of a strong-ribbed oak is, by the aid of a microscope, discoverable in the acorn.

By the opposite party it is urged, that collecting these blotted leaves of fancy, is burying a man of talents in the ruins of his baby-house; and that for the honour of his name, and repose of his soul, they ought to be consigned to the flames, rather than pasted in the portfolio.

I must candidly acknowledge, that for trifles by the hand of Hogarth or Mortimer, I have a kind of religious veneration; but, like the rebuses and riddles of Swift, they are still trifles, and except when considered as tracing the progress of the mind from infancy to manhood, are not entitled to much attention. If examined with this regard, especial care should be taken that their names are not dishonoured by the unmeaning and contemptible productions of inferior artists, some of whose prints have found a place in the catalogue of Hogarth's works. Mr. Nichols properly questions the plate of Æneas in a Storm: he might safely put the same query to Riche's Triumphal Entry into Covent Garden, and a few other plates, which some of the collectors have very positively asserted to be his. The Jack in Office and Pug the Painter, I believe, belong to other collectors. That the design for General Wolfe's monument should ever be supposed the work of Hogarth, has often astonished me. I do not see the most distant resemblance of his manner, in mind, conception, design, or execution.

Many stories, similar to those which are told of the manner that other painters revenged an insult, or supplied the exigencies of the moment, are related of young Hogarth. If true, these volumes would gain little interest by their insertion, for few of them are worthy of a memorial; and if false, they ought not to be admitted.

That a young artist, just emancipated from the obscurity of a silversmith's garret, should be unknown, we naturally suppose; that talents, however exalted, should not be noticed by the public until the professor gave some proofs of superiority, may be readily credited.

That a youth of volatile dispositions, who had neither inheritance nor protection, must frequently want money, follows as certainly as night to day; and we place full confidence in the assertion, when told that he has frequently said, "I remember the time when I have gone moping into the city with scarce a shilling in my pocket; but having received ten guineas there for a plate, returned home, put on my sword and bag, and sallied out again, with all the confidence of a man who had ten thousand pounds in his pocket."

I can believe that the elder Mr. Bowles was his first patron; but when Mr. Nichols informs us, on the authority of Doctor Ducarrel, that this patron offered the young engraver half-a-crown a pound for[34] a plate just finished, rejoice that the inauspicious period when such talents had such patronage[5] is past.

Mr. Horace Walpole well observes, that the history of an artist must be sought in his works. The earliest date I have seen on any of Hogarth's engravings is his own shop-bill, bordered with two figures and two Cupids, and inscribed April 20, 1720. From this and similar mechanic blazonry, he ascended to prints for books, in the execution of which it was not necessary to have much knowledge of the arts. If they were copperplates, the public were satisfied; neither spirit of design, accuracy of drawing, nor delicacy of stroke were demanded. Six engravings, containing six compartments each, for King's History of the Heathen Gods, I should apprehend were among the earliest. I have heard them doubted, and they are not mentioned in either Mr. Walpole's or Mr. Nichols' list; but I believe them to be as certainly Hogarth's as the Rake's Progress.

In two emblematical prints on the lottery, and the South Sea Bubble, published in 1721, there is not much merit; and in the fifteen for Aubrey de la Mottraye's Travels, dated 1723, we only regret that so much time and copper should be wasted.

The Burlington Gate, which appeared in 1724, is in a very superior style, and in the spirit of Callot. With some very well pointed satire on the general passion for masquerades, and other ridiculous raree-shows, it unites a burlesque of Kent the architect, who upon the pediment of his patron's gate is exalted above Raphael and Michael Angelo. From this circumstance I think it probable that the print was engraved as a sort of admission ticket to Sir James Thornhill's academy, which was opened that year. The knight would unquestionably be gratified by this ridicule of his rival, and might in consequence admit the young artist to such a degree of intimacy as enabled him to gain the heart and hand of Miss Thornhill. The burlesque copy of Kent's altar-piece at St. Clement's Church was published in 1725; and fifteen headpieces for Bever's Military Punishments in the same year.[6]

By seventeen small plates, with a head of the[36] author for Butler's Hudibras, printed in 1726, he first became known in his profession. In design, these are almost direct copies from a series inserted in a small edition of the same book, published sixteen years before. Whether this originated in a wish to save himself the trouble of making original designs, or in the twenty booksellers for whom this edition was published, is not easy to determine. These midwives to the Muses might think he was upon safer ground while copying the designs of an artist sanctioned by public approbation, than in following his own inventions, and in this opinion our young engraver might possibly join. Taking these circumstances into the account, I do not agree with Mr. Walpole, when he observes that we are surprised to find so little humour in an undertaking so congenial to his talents. If these prints are considered as copies, they ought not to be produced as a criterion; if compared with those from which they are taken, it is not easy to conceive a greater superiority than he has attained over his originals. Neatness was not required; and for such subjects I prefer the spirited etchings of a Hogarth to the most delicate finishing of a Bartolozzi.

Copies of them are inserted in Grey's Hudibras, published 1744, and Townley's French translation, printed à Londres, 1757. In Grey's edition, the head of Butler is not copied from Hogarth, who certainly had for his pattern White's mezzotint of John Baptist Monoyer the flower painter, from Sir Godfrey Kneller: to any portrait that I have ever seen of Samuel Butler, it has not the faintest resemblance; and how the artist came to give it that name, it is difficult to guess.[7]

The large series on that subject were published the same year, and are thus entitled: Twelve excellent and most diverting prints taken from the celebrated poem of Hudibras, written by Mr. Samuel Butler, exposing the villany and hypocrisy of the times, invented and engraved on twelve copperplates, by William Hogarth, and are humbly dedicated to William Ward, Esq. of Great Houghton, in Northamptonshire, and Mr. Allan Ramsay of Edinburgh.[8]

"What excellence can brass or marble claim!

These papers better do secure thy fame:

Thy verse all monuments does far surpass;

No mausoleum's like thy Hudibras."

Allan Ramsay subscribed for thirty sets. The number of subscribers in all, amounts to 192.

The late Mr. Walker of Queen Anne Street had a sketch of Hudibras and Ralpho, painted by Isaac Fuller, very much in the manner of Hogarth, who I think must have seen, and, in the early part of his life, studied Fuller's pictures.

Seven of the drawings were in the possession of the late Mr. Samuel Ireland, three are in Holland, and two are said to have been in the collection of a person in one of the northern provinces about twenty years ago, but are now probably destroyed. Thus are the works of genius scattered like the Sibyl's leaves.

Hogarth seems to have been particularly partial to this subject; for, previous to engraving the twelve large plates, he painted it in oil. The twelve original pictures, somewhat larger than the prints, are in the possession of the editor of these volumes.

The variety with which the characteristic distinctions of the figures are marked, the firm and spirited touch with which each of the characters are pencilled, is peculiar to this artist: they come into that class of pictures, which to those who have not seen them cannot be described; to those who have, a description is unnecessary.

In a masquerade ticket, published 1727, he has a second time introduced John James Heidegger, of ill-favoured memory. Notwithstanding Lord Chesterfield's wager, that this Surintendant des plaisirs d'Angleterre did not produce a man with so hideous a countenance as his own, and Pope having honoured him with a place in his Dunciad, when describing

"A monster of a fowl,

Something between a Heidegger and owl,"

and his ugliness being in a degree proverbial, an engraving of his face from a mask, taken after his death, and inserted in Lavater's Physiognomy, has strong marks of a benevolent character, and features by no means displeasing or disagreeable.

The print of our decollating Harry and Anna Boleyne, is engraved from a painting once in Vauxhall Gardens.[9] Whatever might be the picture, the[40] print is in every point of view contemptible. His frontispieces to Apuleius and Cassandra, Perseus and Andromeda, John Gulliver, and the Highland Fair, come in precisely the same class. Those to Terræ Filius, the Humours of Oxford, and Tom Thumb, have some traces of comedy.

Various temporary satires on the local follies and vices of the day, which he engraved about this time, are enumerated by Mr. Walpole and Mr. Nichols, but have not in general much merit. The compliments he paid to Sir James Thornhill, by ridiculing William Kent, have been noticed in the preceding pages; but Hogarth's partiality was not confined to the knight, he extended it to the knight's daughter, and finding favour in her sight,—without the formal ceremony of asking consent, or the tedious process of a settlement,—took her to wife. This union being neither sanctioned by her father,[10] nor accompanied with a fortune, compelled him to redouble his professional exertions.

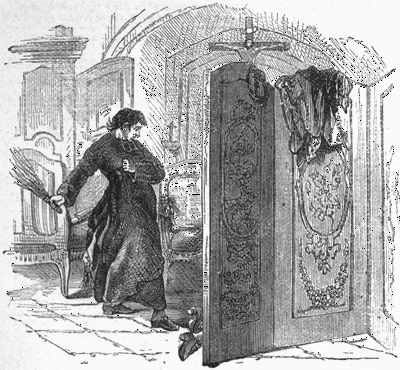

His first large print was Southwark Fair, a natural and highly ludicrous representation of the plebeian amusements of that period; but by the Harlot's Progress,[41] he in 1734 established his character as a painter of domestic history. When his wife's father saw the designs, their originality of idea, regularity of narration, and fidelity of scenery, convinced him that such talents would force themselves into notice, and when known, must be distinguished and patronized. Among a great number of copies which the success of these prints tempted obscure artists to make, there was one set printed on two large sheets of paper, for G. King, Brownlow Street, which, being made with the author's consent, may possibly contain some additions suggested and inserted by Hogarth's directions. In Plate I., beneath the sign of the Bell, PARSONS INTIER BUTT BEAR. In Plate II., to the picture of Jonah under a gourd, a label, Jonah, why art thou angry? and under one of the portraits is written, Mr. Woolston. Below each scene, an inscription describes, in true beaux' spelling; the meaning of the prints, and points out two of the characters to be Colonel Charteris and Sir John Gonson. To the strong resemblance the latter of these delineations bore to the original, Mr. Hogarth is said to be indebted for much of his popularity. The magistrate being universally known, a striking portrait in little would then, as now, have a more numerous band of admirers than the best conceived moral satire.

In 1735, when he published his Rake's Progress with a view of stranding the pirates of the arts, he[42] solicited and obtained an Act to vest an exclusive right in designers and engravers, and restrain the multiplying copies of their works without their consent.

Like many other Acts of Parliament, it was inaccurately worded, and very inadequate to the evil it professed to cure; for Lord Hardwicke determined that no assignee, claiming under an assignment from the original inventor, could receive advantage from it: though after Hogarth's death, the Legislature, by Stat. 7th, Geo. III., granted to his widow a further term of twenty years in the property of her husband's works.

In 1736, at the particular desire of a nobleman, whose name deserves no commemoration, he engraved two prints, entitled Before and After. There are few examples of this artist making designs from the thoughts of others. The Sleeping Congregation, Distressed Poet, Enraged Musician, Strolling Actresses, Modern Midnight Conversation, and many genuine comedies of a new description, where the humour of five acts is brought into one scene, were the productions of his own mind. From these and other mirrors of the times, he was considered as an original author; and being now in the plenitude of his fame,—conceiving himself established in reputation, and conscious of being first in his peculiar walk,—he, on the 25th of Jan. 1744-5, printed proposals, offering the paintings of his Harlot's and Rake's Progress,[43] Four Times of the Day, and Strolling Actresses, to public sale, by an auction of a most singular nature.

"I. Every bidder shall have an entire leaf numbered in the book of sale, on the top of which will be entered his name and place of abode, the sum paid by him, the time when, and for which picture.

"II. That on the last day of sale, a clock (striking every five minutes) shall be placed in the room; and when it hath struck five minutes after twelve, the first picture mentioned in the sale book will be deemed as sold; the second picture, when the clock hath struck the next five minutes after twelve; and so on successively till the whole nineteen pictures are sold.

"III. That none advance less than gold at each bidding.

"IV. No person to bid on the last day, except those whose names were before entered in the book. As Mr. Hogarth's room is but small, he begs the favour that no person, except those whose names are entered in the book, will come to view his paintings on the last day of sale."

A method so novel possibly disgusted the town: they might not exactly understand this tedious formulæ of entering their names and places of abode in a book open to indiscriminate inspection; they might wish to humble an artist, who, by his proposals, seemed to consider that he did the world a favour in suffering them to bid for his works; or the rage for[44] paintings might be confined to the admirers of old masters. Be that as it may, for his nineteen pictures he received only four hundred and twenty-seven pounds seven shillings,—a price by no means equal to their merit.[11]

The prints of the Harlot's Progress had sold much better than those of the Rake's; yet the paintings of the former produced only fourteen guineas each, while those of the latter were sold for twenty-two! That admirable picture, Morning, twenty guineas,—Night, in every point inferior to almost any of his works, six-and-twenty!

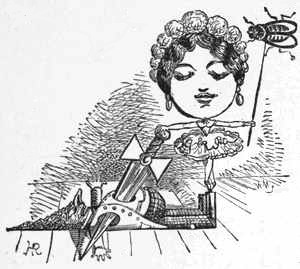

As a ticket of admission to this sale, he engraved the annexed plate.

"In curious paintings I'm exceeding nice,

And know their several beauties by their price;

Auctions and sales I constantly attend,

But choose my pictures by a skilful friend.

Originals and copies, much the same;

The picture's value is the painter's name."

In one corner of this very ludicrous print he has represented an auction-room, on the top of which is a weathercock, in allusion perhaps to Cock the auctioneer. Instead of the four initials for North, East, West, and South, we have P, U, F, S, which, [45]with a little allowance for bad spelling, must pass for Puffs! At the door stands a porter, who from the length of his staff may be high-constable of the old school, and gentleman-usher to the modern connoisseurs. As an attractive show-board, we have an high-finished Flemish head, in one of those ponderous carved and gilt frames, that give the miniatures inserted in them the appearance of a glow-worm in a gravel pit. A catalogue and a carpet (properly enough called the flags of distress) are now the signs of a sale; but here, at the end of a long pole, we have an unfurled standard, emblazoned with that oracular talisman of an auction-room, the fate-deciding hammer. Beneath is a picture of St. Andrew on the cross, with an immense number of fac-similes, each inscribed ditto. Apollo, who is flaying Marsyas, has no mark of a deity, except the rays which beam from his head; he is placed under a projecting branch, and we may truly say the tree shadows what it ought to support. The coolness of poor Marsyas is perfectly philosophical; he endures torture with the apathy of a Stoic. The third tier is made up by a herd of Jupiters and Europas, of which interesting subject, as well as the foregoing, there are dittos, ad infinitum. These invaluable tableaux being unquestionably painted by the great Italian masters, is a proof of their unremitting industry;—their labours evade calculation; for had they acquired the polygraphic art of striking off[46] pictures with the facility that printers roll off copperplates, and each of them attained the age of Methusaleth, they could not have painted all that are exhibited under their names. Nothing is therefore left us to suppose, but that some of these undoubted originals were painted by their disciples.[12] Such are the collections of fac-similes; the other pictures are drawn up in battle array; we will begin with that of St. Francis, the corner of which is in a most unpropitious way driven through Hogarth's Morning. The third painting of the Harlot's Progress suffers equal[47] degradation from a weeping Madonna, while the splendid saloon of the repentant pair in Marriage à la Mode is broken by the Aldobrandini Marriage. Thus far is rather in favour of the ancients; but the aerial combat has a different termination: for, by the riotous scene in the Rake's Progress, a hole is made in Titian's Feast of Olympus; and a Bacchanalian, by Rubens, shares the same fate from the Modern Midnight Conversation. Considered as so much reduced, the figures are etched with great spirit, and have strong character.

In ridicule of the preference given to old pictures, he exercised not only his pencil, but his pen. His advertisement for the sale of the paintings of Marriage à la Mode, inserted in a Daily Advertiser of 1750, thus concludes:

"As, according to the standard so righteously and laudably established by picture-dealers, picture-cleaners, picture-frame makers (and other connoisseurs), the works of a painter are to be esteemed more or less valuable as they are more or less scarce, and as the living painter is most of all affected by the inferences resulting from this and other considerations[49] equally candid and edifying, Mr. Hogarth by way of precaution, not puff, begs leave to urge that probably this will be the last sale of pictures he may ever exhibit, because of the difficulty of vending such a number at once to any tolerable advantage; and that the whole number he has already exhibited of the historical or humorous kind does not exceed fifty, of which the three sets called the Harlot's Progress, the Rake's Progress, and that now to be sold, make twenty: so that whoever has a taste of his own[50] to rely on, and is not too squeamish, and has courage enough to own it, by daring to give them a place in a collection till Time (the supposed finisher, but real destroyer of paintings) has rendered them fit for those more sacred repositories where schools, names, heads, masters, etc., attain their last stage of preferment, may from hence be convinced that multiplicity, at least, of his, Mr. Hogarth's pieces, will be no diminution of their value."[14]

In the same year with the Battle of the Pictures he etched the subscription-ticket for Garrick in Richard III.; where, in a festoon with a mask, a roll of paper, a palette, and a laurel, he combines the drama and the arts.

Soon after the treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle he visited France. A people so different from any he had before seen, and manners so inimical to his own, greatly disgusted him. Ignorance of the language, added[53] to some unpleasant circumstances that had their rise in his own imprudence, form a slight apology for these prejudices; he told them to the world in a view of the Gates of Calais, under which article I have inserted a cantata written by his friend Forest. The portrait in a cap, with a palette, on which is the waving line of beauty and grace, he this year engraved from his own painting. Beneath the frame are three books, labelled, Shakspeare, Milton, Swift; and on one side his faithful and favourite dog Trump. As Hogarth afterwards erased the human face divine, and inserted the divine Churchill in the character of a bear, the print is become very scarce; a small copy adorns the title-page to this volume. Some despicable rhymes on the dog and painter were published in the Scandalizade. Thus do the lines conclude:

"The very self same,—how boldly they strike!

And I can't forbear thinking they're somewhat alike.

Oh fie! to a dog would you Hogarth compare?

Not so,—I say only, they're like as it were;

A respectable pair, all spectators allow,

And that they deserve a description below,

In capital letters, BEHOLD WE ARE TWO."

Those who are personally acquainted with Hogarth deem this print a strong likeness: the picture is remarkably well painted, better than any I have seen from his pencil, except the head of Captain Coram, now in the Foundling Hospital. To that charity Hogarth and several contemporary painters pre[54]sented some of their performances. The attention they obtained from the public induced the members of an academy in St. Martin's Lane to attempt an extension of the plan. With this view, a letter was printed, and sent to the different artists. As it was the cornerstone of that stupendous structure, now become a Royal Academy, I have inserted a copy, with which I was favoured by the gentleman to whom it is addressed.

"TO MR. PAUL SANDBY.

Academy of Painting, Sculpture, etc.,

St. Martin's Lane, Tuesday, October the 23d, 1753.

"Sir,—There is a scheme set on foot for erecting a public academy for the improvement of the arts of painting, sculpture, and architecture; and as it is thought necessary to have a certain number of professors, with proper authority, in order to the making regulations, taking in subscriptions, erecting a building, instructing the students, and concerning all such measures as shall be afterwards thought necessary, your company is desired at the Turk's Head, in Greek Street, Soho, on Tuesday the 13th of November, at five o'clock in the evening precisely, to proceed to the election of thirteen painters, three sculptors, one chaser, two engravers, and two architects; in all twenty-one, for the purposes aforesaid.—I am, Sir, your most humble servant,

"Francis Milner Newton, Sec.

"P.S.—Please to bring the enclosed list, marked with a cross before the names of thirteen painters, three sculptors, one chaser, two engravers, and two architects, as shall appear to you the most able artists in their several professions, and in all other respects the most proper for conducting this design. If you cannot attend, it is expected that you will send your list, sealed and enclosed in a cover, directed to me, and write your name in the cover, without which no regard will be paid to it.

"The list in that case will be immediately taken out of the cover, and mixed with the other lists, so that it shall not be known from whom it came; all imaginable methods being concerted for carrying on this election without favour or partiality. If you know any artist of sufficient merit to be elected a professor, who has been overlooked in drawing out the list, be pleased to write his name, according to his place in the alphabet, with a cross before it."

Their measures did not meet the approbation of Mr. Hogarth. He thought that the establishment of an academy would attract a crowd of young men to neglect studies better suited to their powers, and depart from more profitable pursuits: that every boy who could chalk a straight-lined figure upon a wall, would be led, by his mamma discovering that it was prodigious natural! to mistake inclination for[56] ability, and suppose himself born for shining in the fine arts!—that the streets would be crowded by lads with palettes and portfolios, print-shops be as numerous as porter-houses, and finally, that which ought to be considered as a science, become a trade; and what was still worse, a trade which would not support its professors.

In near fifty years, that have sunk like a sunbeam in the sea, the arts have assumed a new face; they at this period form a very profitable branch of our commerce, and his prophecy pertaining unto print-shops is partly fulfilled.

It has been before observed that Mr. Hogarth, in his own portrait, engraved as a frontispiece to his works, drew a serpentine line on a painter's palette, and denominated it—The line of beauty.

In the preface to his Analysis, he thus describes the consequence of this denomination:—

"The bait soon took, and no Egyptian hieroglyphic ever amused more than it did for a time; painters and sculptors came to me to know the meaning of it, being as much puzzled with it as other people, till it came to have some explanation. Then indeed, but not till then, some found it out to be an old acquaintance of theirs; though the account they gave of its properties was very near as satisfactory as that which a day-labourer, who occasionally uses the lever, could give of that machine as a mechanical power.

"Others, as common face-painters, and copiers of pictures, denied that there could be such a rule either in art or nature, and asserted it was all stuff and madness; but no wonder that these gentlemen should not be ready in comprehending a thing they have little or no business with. For though the picture-copier may sometimes, to a common eye, seem to vie with the original he copies, the artist himself requires no more ability, genius, or knowledge of nature, than a journeyman weaver at the Gobelins, who in working after a piece of painting, bit by bit, scarcely knows what he is about; whether he is weaving a man or a horse; yet at last, almost insensibly, turns out of his loom a fine piece of tapestry, representing, it may be, one of Alexander's battles painted by Le Brun.

"As the above-mentioned print thus involved me in frequent disputes, by explaining the qualities of the line, I was extremely glad to find it (which I had conceived as only part of a system in my own mind) so well supported by a precept of Michael Angelo, which was first pointed out to me by Dr. Kennedy, a learned antiquarian and connoisseur, of whom I afterwards purchased the translation, from which I have taken several passages to my purpose."[15]

To explain this system, he in 1753 commenced author, and published his Analysis, the professed purpose of which was to fix the fluctuating ideas of taste, by establishing a standard of beauty. This he expected would be considered by his contemporaries, as the ancients considered the little soldier modelled by Policletus, the grammar of proportion, criterion of elegance, and rule of perfection. It must be ac[59]knowledged that this was expecting somewhat more than his system deserved; but he received much less. Sheets of good copper were defaced to prove, in the first place, that there was no such line, and in the next, that he had stolen it from the ancients. Some called it the line of deformity, and others the line of drunkenness. By a lady he was more flattered: she told him it was precisely the line[60] which the sun makes in his annual motion round the ecliptic.

His book is divided into chapters, treating of fitness, variety, symmetry, simplicity, intricacy, quantity, lines, forms, composition with the waving line, proportion, light and shade, colouring, attitude, and action. The hypothesis which he endeavours to establish is illustrated by near three hundred explanatory figures, with references to each.

"So vary'd he, and of his tortuous train

Curl'd many a wanton wreath in sight of Eve,

To lure her eye." —Milton.

If the figures which compose this plate are considered independent of the volume, they will appear sufficiently incongruous. He has given us curves and curvatures, straight lines and angles, circles and squares. He has ransacked the garden for examples, and drawn from the shops of the blacksmith, founder, and cabinetmaker, illustrations of his doctrine. To the beauteous and elegant Grecian Venus,[16] he has [61]opposed the venerable English judge, arrayed in an ample robe, with his head enveloped in a periwig like the mane of a lion. The naked majesty of the Apollo Python is contrasted with an English actor, dressed by a modern tailor and barber, to personate a Roman general. The elegant winding lines of an Egyptian sphynx are opposed by a bloated, overcharged, recumbent Silenus. The uniform, coldly correct figures of Albert Durer's drawing-book, that never deviate into grace, to the antique torso, in which Michael Angelo asserted he discovered every principle that gave so grand a gusto to his own works. Three anatomical representations of the muscles which appear in a human leg when the skin is taken off, are placed close to a shapeless pedestal in a shoe and stocking, which by disease has, in the painter's phrase, lost its drawing.

A fine wire, properly twisted round the figure of a cone, represented in Number 26, as giving that elegant wave which adds grace to beauty, is the leading principle on which he builds his system of serpentine lines. Of this ancient grace, opposed to modern air, he could not have selected better examples than[62] Numbers 6 and 7, where Mr. Essex, an English dancing-master, places himself in such an attitude as he thinks the sculptor ought to have given the Antinous, who he is ludicrously enough handing out to dance a minuet.

Number 19 represents the deep-mouth'd Quin! dressed in all the dignity of a playhouse wardrobe, to perform the part of Brutus. That this (and not Coriolanus) is the character meant by the artist, I am inclined to think, from the statue of Julius Cæsar, with a rope round his neck, immediately before him.[17] The rope is passed through a pulley, inserted in one of those triple supporters of great weights, which some of our provincial carpenters call a gallows, and passes to upright beams intersected by poles, in the front of[63] a monument, on which is seated a judge, over whose head is another noosed pulley. How far this may hint at any connection between the law and the rope I cannot determine; but a weeping naked boy, who is seated below, has in his hand what may pass for the model of a gibbet as well as a square. Over the judge's head is written, BIT DECEM. 1752, ÆTATIS; the O preceding BIT is covered: I apprehend the same judge may be found in a print of THE BENCH.

A new order was Hogarth's favourite idea: he has here made an attempt at a capital composed of hats and periwigs.[18] An infant with a man's wig and cap on, is a miniature representation of Mr. Quin's Roman general; and a monkey child, led by a travelling tutor, gives the painter's opinion of those young gentlemen who visited Rome for improvement in connoisseurship.[19] It is copied from a burlesque of Cav. Ghezzi, etched by Mr. Pond.

"Though rosy youth embloom the sprightly fair,

And beauty mold her with a lover's care,

If motion to the form denies a grace,

Vain is the beauty that adorns the face."

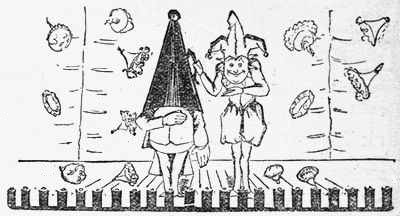

The fatigued figures that labour through this dance, Mr. Hogarth in his 16th chapter thus explains:

OF ATTITUDE.

"Such dispositions of the body and limbs as appear most graceful when seen at rest, depend upon gentle winding contrasts, mostly governed by the precise serpentine line, which in attitudes of authority are more extended and spreading than ordinary, but reduced somewhat below the medium of grace in those of negligence and ease; and as much exaggerated in insolent and proud carriage, or distortions of pain (see Number 9, in Plate I.), as lessened and[65] contracted into plain and parallel lines, to express meanness, awkwardness, and submission.

"The general idea of an action, as well as of an attitude, may be given with a pencil in very few lines. It is easy to conceive that the attitude of a person upon the cross may be fully signified by the true straight lines of the cross; so the extended manner of St. Andrew's crucifixion is wholly understood by the X-like cross.

"Thus, as two or three lines at first are sufficient to show the intention of an attitude, I will take this opportunity of presenting my reader with the sketch of a country-dance, in the manner I began to set out the design. In order to show how few lines are necessary to express the first thoughts, as to different attitudes, see Number 71 (top of the plate), which describes in some measure the several figures and actions, mostly of the ridiculous kind, that are represented in the chief part of Plate II.

"The most amiable person may deform his general appearance by throwing his body and limbs into plain lines; but such lines appear still in a more disagreeable light in people of a particular make. I have therefore chose such figures as I thought would agree best with my first score of lines, Number 71.

"The two parts of curves next to 71, served for the figures of the old woman and her partner, at the farther end of the room. The curve, and two straight[66] lines at right angles, gave the hint for the fat man's sprawling posture. I next resolved to keep a figure within the bounds of a circle, which produced the upper part of the fat woman, between the fat man and the awkward one in the bag-wig, for whom I had made a sort of an X. The prim lady his partner, in the riding habit, by pecking back her elbows, as they call it, from the waist upwards, made a tolerable D, with a straight line under it, to signify the scanty stiffness of her petticoat; and the Z stood for the angular position the body makes with the legs and thighs of the affected fellow in the tie-wig; the upper part of his plump partner was confined to an O, and this changed into a P, served as a hint for the straight lines behind. The uniform diamond of a card was filled up by the flying dress, etc. of the little capering figure in the Spencer wig, whilst a double L marked the parallel position of his poking partner's hands and arms: and lastly, the two waving lines were drawn for the more genteel turns of the two figures at the hither end."[20]

Such is the author's alphabetical analysis of his[67] serpentine system, which some of my readers may possibly think borders on the visionary: certain it is, that however he may have failed in his two specimens of grace, those of awkwardness are carried as far as they could have been in a Russian dance, when Peter the Great ordained that no lady of any age should presume to get drunk before nine o'clock.

I have seen the print framed as a companion to Guido's Aurora; nothing surely can form a stronger contrast to the golden age, when

"Universal Pan,

Knit with the Graces and the Hours, in dance

Led on th' eternal Spring."

They are said to represent the Wanstead assembly, and contain portraits of the first Earl Tylney, his Countess, their children, tenants, etc. In the tall young lady he has evidently aimed at Milton's description of motion—smooth sliding without step; but her air is affected. Her noble partner was originally intended for a portrait of the present King, then Prince of Wales; and though I learn from Mr. Walpole that it was afterward altered to the first[68] Duke of Kingston, still retains so much of its original designation as to bear a resemblance.

The design was made about the year 1728, and might be a just representation of the Wanstead belles and beaux; but since that period we have had so many ship-loads of grace imported from the Continent, and such numbers of well-educated gentlemen,[21] who have exerted their talents in perfecting this divine art, that the picture would not do for the present day.

The sighing Celadon, privately delivering a letter fraught with love to his fair Amelia, is evidently the native of a country that has furnished many of our English heiresses with good husbands. Her impatient father's watch is precisely twelve, which determines what were then thought late hours, on so particular an occasion as a wedding-ball, the sketch being[69] originally designed for a series illustrative of a happy marriage.[22]

Hogarth is said to have boasted that each of the hats which lie upon the floor are so characteristic of their respective proprietors, that any man who understood the form of the human caput might assign each to its owner. Among them is a cushion, which was formerly part of the ball-room furniture, for what was called the cushion-dance, in the progress of which the gentleman kneels down and salutes his partner.

The light diffused from the chandelier shows an attention to nature worthy the study and imitation of many modern painters, whose figures are illuminated by beams unaccountable!

Thus much may suffice for the prints; as to the book, a pen was not Hogarth's instrument. His life had been devoted to the study of the pencil; and[70] however clear in idea, he felt the consciousness that his language might be rendered more worthy public attention by the advice and assistance of literary friends. This he acknowledges, in the style of a man who felt that his character did not depend on the power of constructing a sentence, in which branch of the work he was aided by Doctor Hoadley, Doctor Morrell, and his friend the Reverend Mr. Townley,[23][71] whose son told me, that when his father corrected the first sheet, he found a plentiful crop of errors; the second and third were less incorrect; and the fourth much more accurate than the preceding. Such is the power of genius, whatever its direction.

I will not go so far as Mr. Ralph, who says, "that by means of this volume composition is become a science; the student knows what he is in search of,[72] the connoisseur what to praise, and fancy or fashion, or prescription, will usurp the hackneyed name of taste no more; because I think with Lady Luxborough, that in the line of beauty no man can literally fix the precise degree of obliquity;" but I think with the same lady, "that between his pencil and his pen, he conveys an idea which enables one to conceive his meaning,"[73] and that he gives many hints which may be of great use to the artist, actor, dancer, or connoisseur.[24]

Though many profitable opportunities were offered by the politics of the day, it does not appear that Hogarth ever degraded his character by either servile adulation or interested abuse of the powers which were.

In an account of the March to Finchley, it will be found that when the print was presented to George II., the king returned it in a way that must have mortified and wounded the artist, who, though he was tremblingly alive to professional indignity, made no graven retaliation. He could not therefore be considered as an opponent it was proper to silence, or as an advocate[74] it was necessary to retain; notwithstanding which, on the 16th of July 1757, when Mr. Thornhill (son to Sir James) resigned his place of sergeant painter, William Hogarth was appointed his successor; and very soon after, engaged in a pencil competition that did not terminate to his advantage.

I have had frequent occasion to mention the opinion he entertained of ancient paintings. By ridiculing copies and contemptible originals, he got a habit of laughing at them all; and when, in 1758, Sir Thomas Sebright, at Sir Luke Schaub's sale, gave £404, 5s. for Correggio's Sigismunda, [25] Hogarth, in evil hour, asserted that, were he paid as good a price, he could paint a better picture. Sir Richard (afterwards Lord) Grosvenor unluckily gave him an order for the same subject, guarded with the qualifying monosyllable IF. The work was finished,—sent to the purchaser,—and returned to the artist,—because,—as the ironical epistle[26] which accompanied it expressed,—"Contemplating such a subject must excite melancholy ideas, which a curtain being drawn before it would not diminish."[27]

This rejection produced a letter from Hogarth to a friend, relating the whole transaction, in rhymes that might perhaps give our painter a niche amongst the minor poets; but which, having neither the harmony of Pope nor the ardour of Dryden, shall find no place here. The prophecy it concludes with has not been absolutely fulfilled, but in the form of a wish may be a suitable motto for the next print.

"Let the picture rust;

Perhaps Time's price-enhancing dust,

As statues moulder into earth,

When I'm no more, may mark its worth;

And future connoisseurs may rise,

Honest as ours, and full as wise,

To puff the piece, and painter too,

And make me then what Guido's now."

—Hogarth's Epistle.

A competition with either Guido or Furino would to any modern painter be an enterprise of danger: to Hogarth it was more peculiarly so, from the public justly conceiving that the representation of elevated distress was not his forte, and his being surrounded by an host of foes, who either dreaded satire or envied genius. The connoisseurs considering the challenge as too insolent to be forgiven,—before his picture appeared, determined to decry it. The painters rejoiced in his attempting what was likely to end in[76] disgrace; and to satisfy those who had formed their ideas of Sigismunda upon the inspired page of Dryden, was no easy task.

The bard has consecrated the character, and his heroine glitters with a brightness that cannot be transferred to the canvas. Mr. Walpole's description, though equally radiant, is too various for the utmost powers of the pencil.

Hogarth's Sigismunda, as this gentleman poetically expresses it, "has none of the sober grief, no dignity of suppressed anguish, no involuntary tear, no settled meditation on the fate she meant to meet, no amorous warmth turned holy by despair; in short, all is wanting that should have been there, all is there that such a story would have banished from a mind capable of conceiving such complicated woe; woe so sternly felt, and yet so tenderly." This glowing picture presents to the mind a being whose contending passions may be felt, but were not delineated even by Correggio. Had his tints been aided by the grace and greatness of Raphael, they must have failed.

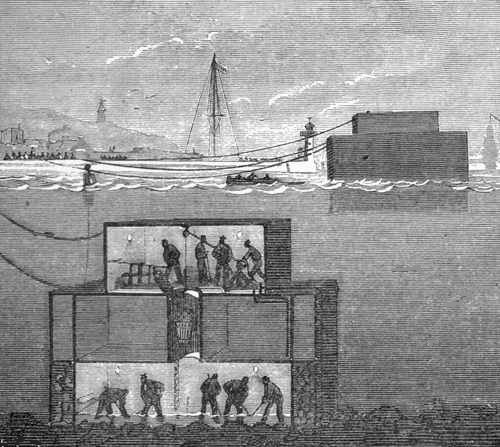

The author of the Mysterious Mother sought for sublimity, where the artist strictly copied nature, which was invariably his archetype, but which the painter, who soars into fancy's fairy regions, must in a degree desert. Considered with this reference, though the picture has faults, Mr. Walpole's satire is surely too severe. It is built upon a comparison[77] with works painted in a language of which Hogarth knew not the idiom,—trying him before a tribunal whose authority he did not acknowledge; and from the picture having been in many respects altered after the critic saw it, some of the remarks become unfair. To the frequency of these alterations we may attribute many of the errors:[28] the man who has not confidence in his own knowledge of the leading principles on which his work ought to be built, will not render it perfect by following the advice of his friends. Though Messrs. Wilkes and Churchill dragged his heroine to the altar of politics, and [78]mangled her with a barbarity that can hardly be paralleled, except in the history of her husband,—the artist retained his partiality, which seems to have increased in exact proportion to their abuse. The picture being thus contemplated through the medium of party prejudice, we cannot wonder that all its imperfections were exaggerated. The painted harlot of Babylon had not more opprobrious epithets from the first race of reformers, than the painted Sigismunda of Hogarth from the last race of patriots.[30]

When a favourite child is chastised by his preceptor, a partial mother redoubles her caresses. Hogarth, estimating this picture by the labour he had bestowed upon it, was certain that the public were prejudiced, and requested, if his wife survived him, she would not sell it for less than five hundred pounds. Mrs. Hogarth acted in conformity to his[79] wishes; but after her death, the painting was purchased by Messrs. Boydell, and exhibited in the Shakspeare Gallery. The colouring, though not brilliant, is harmonious and natural: the attitude, drawing, etc., may be generally conceived by the print engraved by Mr. Benjamin Smith. I am much inclined to think, that if some of those who have been most severe in their censures, had consulted their own feelings, instead of depending upon connoisseurs, poor Sigismunda would have been in higher estimation. It has been said that the first sketch was made from Mrs. Hogarth, at the time she was weeping over the corse of her mother.

Hogarth once intended to have appealed from the critics' fiat to the world's opinion, and employed Mr. Basire to make an engraving, which was begun, but set aside for some other work, and never completed.[31]

"To nature and yourself appeal,

Nor learn of others what to feel."—Anon.

This animated satire was etched as a receipt-ticket for a print of Sigismunda. It represents Time, seated upon a mutilated statue, and smoking a landscape, through which he has driven his scythe, to give proof of its antiquity,—not only by sober, sombre tints, but by an injured canvas. Beneath the easel on which it is fixed the artist has placed a capacious jar, on which is written VARNISH,—to bring out the beauties of this inestimable assemblage of straight lines. The frame is dignified with a Greek motto:

Crates,—Ὁ γὰρ χρόνος μ' ἔκαμψε, τέκτων μὲν σοφὸς,

Ἅπαντα δ' ἐργαζόμενος ἀσθενέστερα.

See Spectator, vol. ii. p. 83.

This, though not engraved with precise accuracy, is sufficiently descriptive of the figure.

Time has bent me double; and Time, though I confess he is a great artist, weakens all he touches.

"From a contempt" (says Mr. Walpole) "of the[81] ignorant virtuosi of the age, and from indignation at the impudent tricks of picture-dealers,[32] whom he saw continually recommending and vending vile copies to bubble-collectors, and from having never studied, indeed having seen few good pictures of the great Italian masters, he persuaded himself that the praises bestowed on those glorious works were nothing but the effects of prejudice. He talked this language till he believed it; and having heard it often asserted, as is true, that Time gives a mellowness to colours, and improves them, he not only denied the proposition, but maintained that pictures only grew black and[82] worse by age, not distinguishing between the degrees in which the proposition might be true or false."

Whether Mr. Walpole's remarks are right or wrong, Hogarth has admirably illustrated his own doctrine, and added to his burlesque, by introducing the fragments of a statue, below which is written,

As statues moulder into worth. P. W.

By part of this print being in mezzotinto and the remainder etched, it has a singularly striking and spirited appearance.

Hogarth, the following year, published that admirable satire, The Medley, which completely refutes the[83] reproach thrown on his declining talents by his political opponents, whose violent, and in some respects vindictive attack, is erroneously said to have hastened his death. That he was wounded with a barbed spear, hurled by the hand of a friend, it is reasonable to suppose; but armed with the mailed coat of conscious superiority, he could not be wounded mortally. What!—broken-hearted by a rhyme!—pelted to death with ballads!—He was too proud! I am told by those who knew him best, that the little mortification he felt, did not arise from the severity of the satire, but from a recollection of the terms on which he had lived with the satirist.

To the painter's recriminations in this party jar, Mr. Nichols I suppose alludes, page 97 of his Anecdotes, where he says, that "in his political conduct and attachments, Hogarth was at once unprincipled and variable." These are harsh and heavy charges, but I am to learn on what they are founded. He never embarked with any party, nor did he publish a political print before the year 1762; and the principles he there professes he retained until his death.

In the same page of the Anecdotes, I find, after a complimentary quotation from one of Mr. Hayley's poems, several severe strictures to which I cannot assent.[33] The assertion, that all his powers of delighting[84] were confined to his pencil, is in a degree refuted by the Analysis. That he was rarely admitted into polite circles, I can readily believe; but if by polite circles, Mr. Nichols means those persons of honour who deem dress the grand criterion of distinction, think making an easy bow the first human acquirement, and Lord Chesterfield's code the whole duty of man,—the artist had no great cause to regret the loss of such society. But his sharp corners not being rubbed off by collision with these polite circles, he was, to the last, a gross, uncultivated man. Engaged in ascertaining the principles of his art, he had not leisure to study the principles of politeness; but by those who lived with him in habits of intimacy, I am told he was by no means gross.