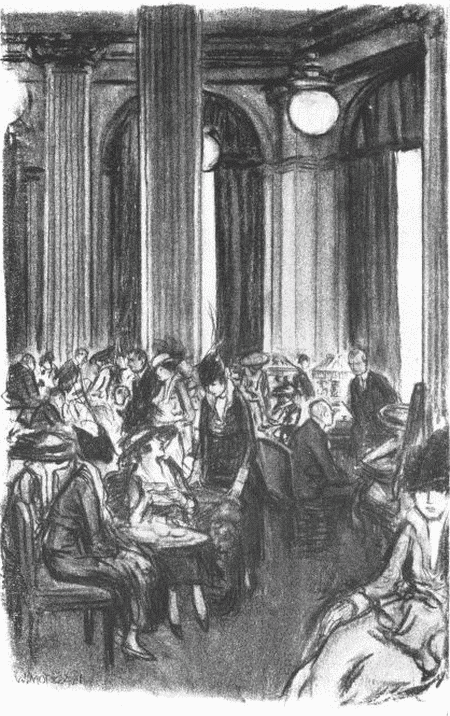

The St. Francis at tea-time.—With her hotels San Francisco is New

York, but with her people she is San Francisco—which comes near

being the apotheosis of praise

The St. Francis at tea-time.—With her hotels San Francisco is New

York, but with her people she is San Francisco—which comes near

being the apotheosis of praise

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Abroad at Home

American Ramblings, Observations, and Adventures of Julian Street

Author: Julian Street

Release Date: April 25, 2011 [eBook #35965]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ABROAD AT HOME***

THE NEED OF CHANGE

Fifth Anniversary Edition. Illustrated by James Montgomery Flagg. Cloth, 50 cents net. Leather, $1.00 net.

PARIS À LA CARTE

"Gastronomic promenades" in Paris. Illustrated by May Wilson Preston. Cloth, 60 cents net.

WELCOME TO OUR CITY

Mr. Street plays host to the stranger in New York. Illustrated by James Montgomery Flagg and Wallace Morgan. Cloth, $1.00 net.

SHIP-BORED

Who hasn't been? Illustrated by May Wilson Preston. Cloth, 50 cents net.

ABROAD AT HOME Cheerful ramblings and adventures in American cities and other places. Illustrated by Wallace Morgan. Cloth, $2.50 net.

For Children

THE GOLDFISH

A Christmas story for children between six and sixty. Colored Illustrations and page Decorations. Cloth, 70 cents net.

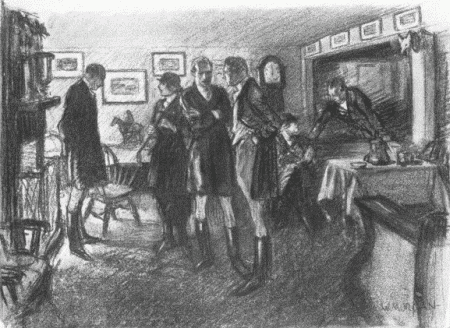

The St. Francis at tea-time.—With her hotels San Francisco is New

York, but with her people she is San Francisco—which comes near

being the apotheosis of praise

The St. Francis at tea-time.—With her hotels San Francisco is New

York, but with her people she is San Francisco—which comes near

being the apotheosis of praise

the companion of my first railroad journey

The Author takes this opportunity to thank the old friends, and the new ones, who assisted him in so many ways, upon his travels. Especially, he makes his affectionate acknowledgment to his wise and kindly companion, the Illustrator, whose admirable drawings are far from being his only contribution to this volume.

—J. S.

New York,

October, 1914.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| STEPPING WESTWARD | ||

| I | STEPPING WESTWARD | 3 |

| II | BIFURCATED BUFFALO | 21 |

| III | CLEVELAND CHARACTERISTICS | 40 |

| IV | MORE CLEVELAND CHARACTERISTICS | 48 |

| MICHIGAN MEANDERINGS | ||

| V | DETROIT THE DYNAMIC | 65 |

| VI | AUTOMOBILES AND ART | 77 |

| VII | THE MÆCENAS OF THE MOTOR | 91 |

| VIII | THE CURIOUS CITY OF BATTLE CREEK | 105 |

| IX | KALAMAZOO | 121 |

| X | GRAND RAPIDS THE "ELECT" | 127 |

| CHICAGO | ||

| XI | A MIDDLE-WESTERN MIRACLE | 139 |

| XII | FIELD'S AND THE "TRIBUNE" | 150 |

| XIII | THE STOCKYARDS | 164 |

| XIV | THE HONORABLE HINKY DINK | 173 |

| XV | AN OLYMPIAN PLAN | 181 |

| XVI | LOOKING BACKWARD | 187 |

| "IN MIZZOURA" | ||

| XVII | SOMNOLENT ST. LOUIS | 201 |

| XVIII | THE FINER SIDE | 221 |

| XIX | HANNIBAL AND MARK TWAIN | 237 |

| XX | PIKE AND POKER | 253 |

| XXI | OLD RIVER DAYS | 267 |

| THE BEGINNING OF THE WEST | ||

| XXII | KANSAS CITY | 275 |

| XXIII | ODDS AND ENDS | 291 |

| XXIV | COLONEL NELSON'S "STAR" | 302 |

| XXV | KEEPING A PROMISE | 313 |

| XXVI | THE TAME LION | 323 |

| XXVII | KANSAS JOURNALISM | 337 |

| XXVIII | A COLLEGE TOWN | 345 |

| XXIX | MONOTONY | 365 |

| THE MOUNTAINS AND THE COAST | ||

| XXX | UNDER PIKE'S PEAK | 379 |

| XXXI | HITTING A HIGH SPOT | 400 |

| XXXII | COLORADO SPRINGS | 417 |

| XXXIII | CRIPPLE CREEK | 434 |

| XXXIV | THE MORMON CAPITAL | 439 |

| XXXV | THE SMITHS | 454 |

| XXXVI | PASSING PICTURES | 465 |

| XXXVII | SAN FRANCISCO | 474 |

| XXXVIII | "BEFORE THE FIRE" | 488 |

| XXXIX | AN EXPOSITION AND A "BOOSTER" | 498 |

| XL | NEW YORK AGAIN | 507 |

| The St. Francis at tea-time.—With her hotels San Francisco is New

York, but with her people she is San Francisco—which comes near being the apotheosis of praise. Frontispiece | FACING PAGE |

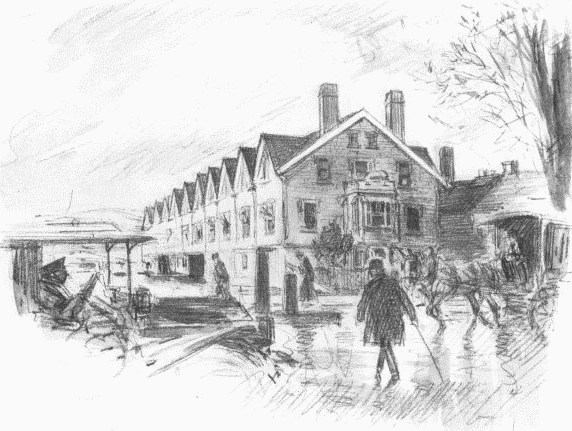

| I was moving about my room, my hands full of hairbrushes and toothbrushes

and clothesbrushes and shaving brushes; my head full of railroad trains, and hills, and plains, and valleys | 5 |

| A dusky redcap took my baggage | 12 |

| What scenes these black, pathetic people had passed through—were

passing through! Why did they not look up in wonderment?. | 17 |

| We made believe we wanted to go out and smoke. And as we left

our seats she made believe she didn't know that we were going. | 23 |

| The gentleman who favored linen mesh was a fat, prosperous-looking

person, whose gold-rimmed spectacles reflected flying lights from out of doors | 26 |

| In a few hours there was enough shame around us to have lasted all

the reformers and muckrakers I know a whole month | 32 |

| My companion and I made excuses to go downstairs and wash our

hands in the public washroom, just for the pleasure of doing so without fear of being attacked by a swarthy brigand with a brush | 35 |

| I was prepared to take the field against all comers, not only in favor

of simplicity, but in favor of anything and everything which was favored by my hostess | 38 |

| Chamber of Commerce representatives were with us all the first day

and until we went to our rooms, late at night | 43 |

| It is an Elizabethan building, with a heavy timbered front, suggesting

some ancient, hospitable, London coffee house where wits of old were used to meet | 46 |

| In this charming, homelike old building, with its grandfather's clock,

its Windsor chairs, and its open wood fires, a visitor finds it hard to realize that he is in the "west" | 53 |

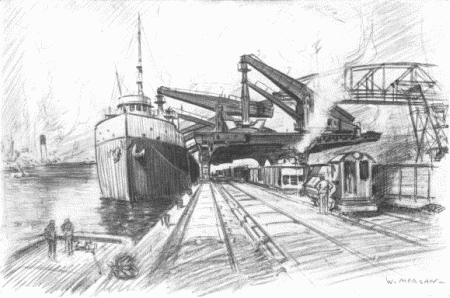

| Down by the docks we saw gigantic, strange machines, expressive of

Cleveland's lake commerce—machines for loading and unloading ships in the space of a few hours | 60 |

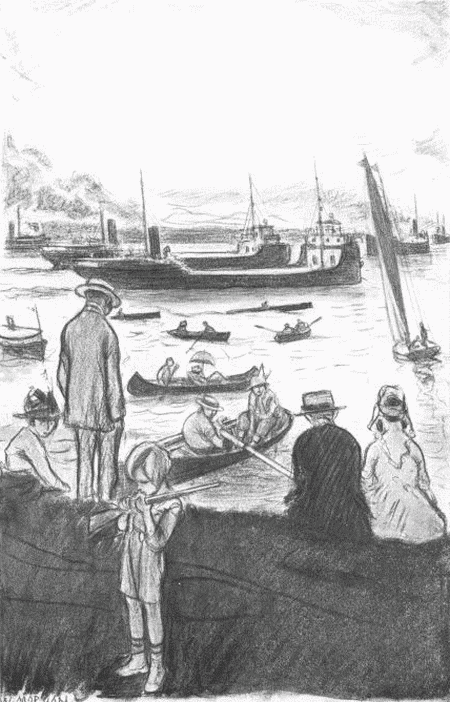

| In midstream passes a continual parade of freighters ... and in

their swell you may see, teetering, all kinds of craft, from proud white yachts to canoes | 71 |

| The automobile has not only changed Detroit from a quiet old town

into a rich, active city, but upon the drowsy romance of the old days it has superimposed the romance of modern business | 74 |

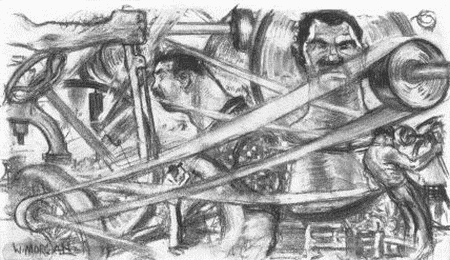

| Of course there was order in that place, of course there was system—relentless

system—terrible "efficiency"—but to my mind it expressed but one thing, and that thing was delirium | 97 |

| Never, since then, have I heard men jeering over women as they look

in dishabille, without wondering if those same men have ever seen themselves clearly in the mirrored washroom of a sleeping car | 112 |

| "Can that stuff," admonished Miss Buck in her easy, offhand manner | 117 |

| She was saying to herself (and, unconsciously, to us, through the

window): "If I had played that hand, I never should have done it that way!" | 124 |

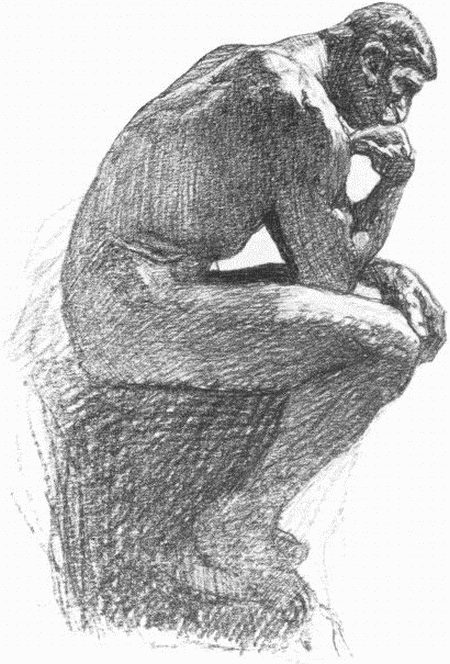

| Rodin's "Thinker" | 145 |

| Chicago's skyline from the docks.... A city which rebuilt itself after

the fire; in the next decade doubled its size; and now has a population of two million, plus a city of about the size of San Francisco | 160 |

| Two rabbis, old bearded men, performed the rites with long, slim,

shiny blades | 177 |

| As I stood there, studying the temperament of pigs, I saw the butcher

looking up at me.... I have never seen such eyes | 192 |

| The bold front of Michigan Avenue along Grant Park ... great

buildings wreathed in whirling smoke and that allegory of infinity which confronts one who looks eastward | 196 |

| The dilapidation of the quarter has continued steadily from Dickens's

day to this, and the beauty now to be discovered there is that of decay and ruin | 205 |

| The three used bridges which cross the Mississippi River at St. Louis

are privately controlled toll bridges | 212 |

| The skins are handled in the raw state ... with the result that the

floor of the exchange is made slippery by animal fats, and that the olfactory organs encounter smells not to be matched in any zoo | 221 |

| St. Louis needs to be taken by the hand and led around to some municipal-improvement

tailor, some civic haberdasher | 225 |

| We came upon the "Mark Twain House."... And to think that,

wretched as this place was, the Clemens family were forced to leave it for a time because they were too poor to live there | 240 |

| At one side is an alley running back to the house of Huckleberry Finn,

and in that alley stood the historic fence which young Sam Clemens cajoled the other boys into whitewashing for him | 244 |

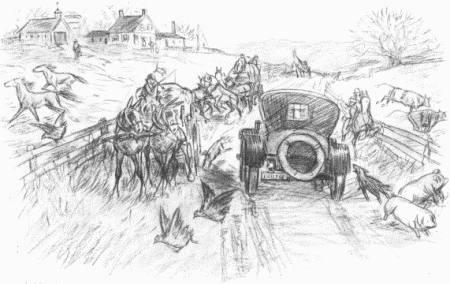

| Never outside of Brittany and Normandy have I seen roads so full of

animals as those of Pike County | 253 |

| Mr. Roberts is a wonder—nothing less. There's a book in him, and

I hope that somebody will write it, for I should like to read that book | 268 |

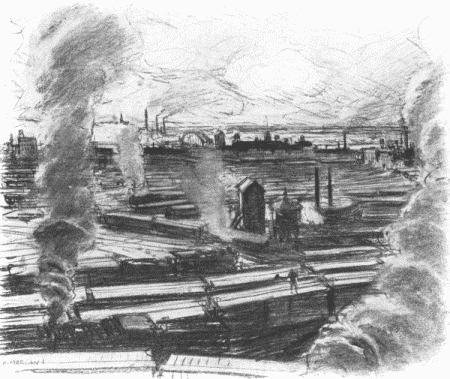

| Looking down from Kersey Coates Drive, one sees ... the appalling

web of railroad tracks, crammed with freight cars, which seen through a softening haze of smoke, resemble a relief map—strange, vast and pictorial | 289 |

| Colonel Nelson is a "character." Even if he didn't own the "Star," ...

he would be a "character."... I have called him a volcano; he is more like one than any other man I have ever met | 304 |

| Mr. Fish informed me that the waters of Excelsior Springs resemble

the waters of Homburg, the favorite watering place of the late King Edward—or, rather, I think he put it the other way round | 322 |

| We strolled in the direction of the old house, that house of tragedy in

which the family lived in the troublous times.... It was there that the Pinkertons threw the bomb | 328 |

| It was Frank James.... He looks more like a prosperous farmer or

the president of a rural bank than like a bandit. In his manner there is a strong note of the showman | 335 |

| The campus seems to have "just growed."... Nevertheless, there is

a sort of homely charm about the place, with its unimposing, helter-skelter piles of brick and stone | 353 |

| Even at sea the great bowl of the sky had never looked to me so vast | 368 |

| The little towns of western Kansas are far apart and have, like the

surrounding scenery, an air of sadness and desolation | 373 |

| In the lobby of the Brown Palace Hotel we saw several old fellows,

sitting about, looking neither prosperous nor busy, but always talking mines. A kind word, or even a pleasant glance, is enough to set them off | 380 |

| "Ain't Nature wonderful!" | 405 |

| I was by this time very definitely aware that I had my fill of winter

motoring in the mountains. The mere reluctance I felt as we began to climb had now developed into a passionate desire to desist | 412 |

| The homes of Colorado Springs really explain the place and the society

is as cosmopolitan as the architecture | 417 |

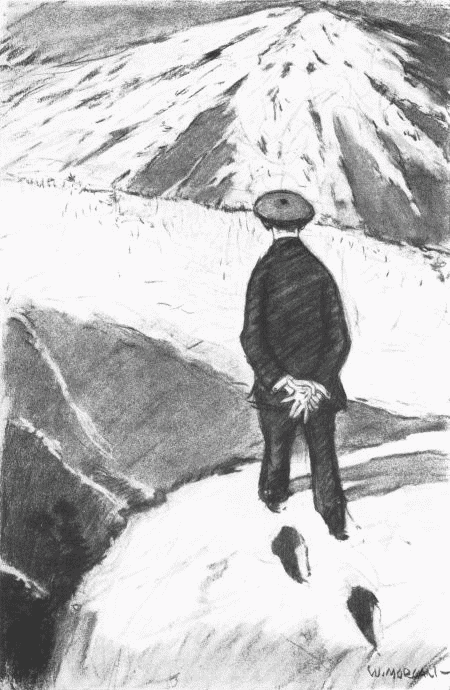

| On the road to Cripple Creek we were always turning, always turning

upward | 432 |

| We were invited to meet the President of the Mormon Church and

some members of his family at the Beehive House, his official residence | 452 |

| The Lion House—a large adobe building in which formerly resided

the rank and file of Brigham Young's wives | 461 |

| The Cliff House has a Sorrento setting and hectic turkey-trotting

nights | 468 |

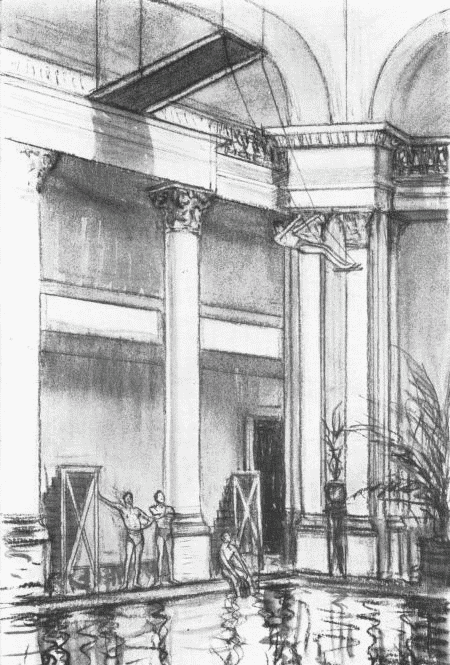

| The Salt-water pool, Olympic Club, San Francisco | 477 |

| The switchboard of the Chinatown telephone exchange is set in a

shrine and the operators are dressed in Chinese silks | 496 |

| We believed we had encountered every kind of "booster" that creeps,

crawls, walks, crows, cries, bellows, barks or brays, but it remained for the Exposition to show us a new specimen | 504 |

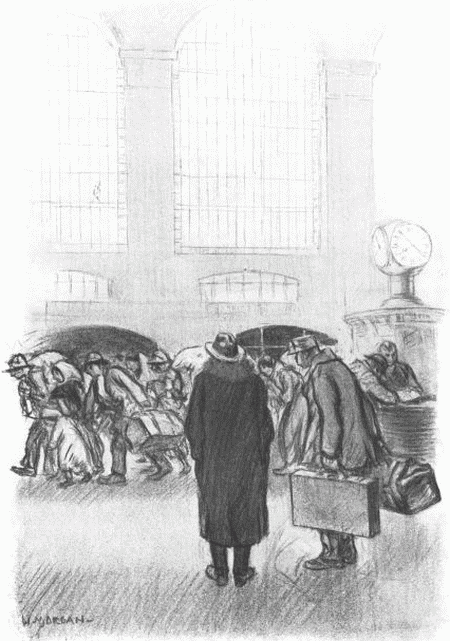

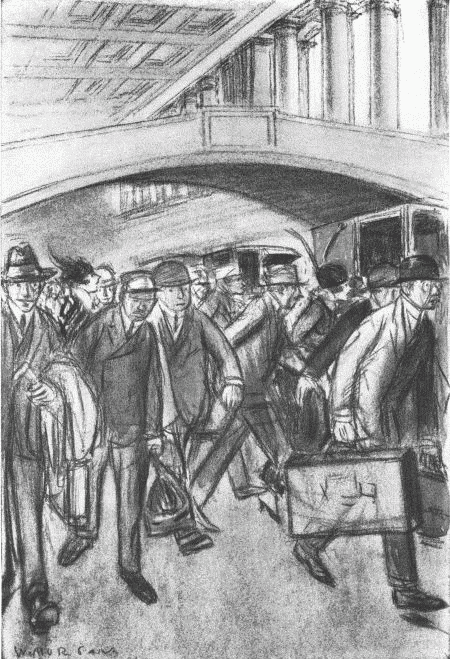

| New York—Everyone is in a hurry. Everyone is dodging everyone

else. Everyone is trying to keep his knees from being knocked by swift-passing suitcases | 513 |

"What, you are stepping westward?"—"Yea."

—'Twould be a wildish destiny,

If we, who thus together roam

In a strange Land, and far from home,

Were in this place the guests of Chance:

Yet who would stop or fear to advance,

Though home or shelter he had none,

With such a sky to lead him on?

—Wordsworth.

For some time I have desired to travel over the United States—to ramble and observe and seek adventure here, at home, not as a tourist with a short vacation and a round-trip ticket, but as a kind of privateer with a roving commission. The more I have contemplated the possibility the more it has engaged me. For we Americans, though we are the most restless race in the world, with the possible exception of the Bedouins, almost never permit ourselves to travel, either at home or abroad, as the "guests of Chance." We always go from one place to another with a definite purpose. We[ 4] never amble. On the boat, going to Europe, we talk of leisurely trips away from the "beaten track," but we never take them. After we land we rush about obsessed by "sights," seeing with the eyes of guides and thinking the "canned" thoughts of guidebooks.

In order to accomplish such a trip as I had thought of I was even willing to write about it afterward. Therefore I went to see a publisher and suggested that he send me out upon my travels.

I argued that Englishmen, from Dickens to Arnold Bennett, had "done" America; likewise Frenchmen and Germans. And we have traveled over there and written about them. But Americans who travel at home to write (or, as in my case, write to travel) almost always go in search of some specific thing: to find corruption and expose it, to visit certain places and describe them in detail, or to catch, exclusively, the comic side. For my part, I did not wish to go in search of anything specific. I merely wished to take things as they might come. And—speaking of taking things—I wished, above all else, to take a good companion, and I had him all picked out: a man whose drawings I admire almost as much as I admire his disposition; the one being who might endure my presence for some months, sharing with me his joys and sorrows and collars and cigars, and yet remain on speaking terms with me.

The publisher agreed to all. Then I told my New York friends that I was going.

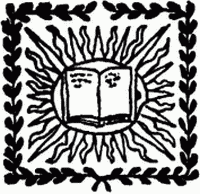

I was moving about my room, my hands full of hairbrushes and toothbrushes

and clothesbrushes and shaving brushes; my head full of railroad trains, and hills,

and plains, and valleys

I was moving about my room, my hands full of hairbrushes and toothbrushes

and clothesbrushes and shaving brushes; my head full of railroad trains, and hills,

and plains, and valleys

They were incredulous. That is the New York atti[ 5]tude of mind. Your "typical New Yorker" really thinks that any man who leaves Manhattan Island for any destination other than Europe or Palm Beach must be either a fool who leaves voluntarily or a criminal taken off by force. For the picturesque criminal he may be sorry, but for the fool he has scant pity.

At a farewell party which they gave us on the night before we left, one of my friends spoke, in an emotional moment, of accompanying us as far as Buffalo. He spoke of it as one might speak of going up to Baffin Land to see a friend off for the Pole.

I welcomed the proposal and assured him of safe conduct to that point in the "interior." I even showed him Buffalo upon the map. But the sight of that wide-flung chart of the United States seemed only to alarm him. After regarding it with a solemn and uneasy eye he shook his head and talked long and seriously of his responsibilities as a family man—of his duty to his wife and his limousine and his elevator boys.

It was midnight when good-bys were said and my companion and I returned to our respective homes to pack. There were many things to be put into trunks and bags. A clock struck three as my weary head struck the pillow. I closed my eyes. Then when, as it seemed to me, I was barely dozing off there came a knocking at my bedroom door.

"What is it?"[ 6]

"Six o'clock," replied the voice of our trusty Hannah.

As I arose I knew the feelings of a man condemned to death who hears the warden's voice in the chilly dawn: "Come! It is the fatal hour!"

When, fifteen minutes later, doubting Hannah (who knows my habits in these early morning matters) knocked again, I was moving about my room, my hands full of hairbrushes and toothbrushes and clothes brushes and shaving brushes; my head full of railroad trains, and hills, and plains and valleys, and snow-capped mountain peaks, and smoking cities and smoking-cars, and people I had never seen.

The breakfast table, shining with electric light, had a night-time aspect which made eggs and coffee seem bizarre. I do not like to breakfast by electric light, and I had done so seldom until then; but since that time I have done it often—sometimes to catch the early morning train, sometimes to catch the early morning man.

Beside my plate I found a telegram. I ripped the envelope and read this final punctuation-markless message from a literary friend:

you are going to discover the united states dont be afraid to say so

That is an awful thing to tell a man in the very early morning before breakfast. In my mind I answered with the cry: "But I am afraid to say so!"

And now, months later, I am still afraid to say so, be[ 7]cause, despite a certain truth the statement may contain, it seems to me to sound ridiculous, and ponderous, and solemn with an asinine solemnity.

It spoiled my last meal at home—that well-meant telegram.

I had not swallowed my second cup of coffee when, from her switchboard, a dozen floors below, the operator telephoned to say my taxi had arrived; whereupon I left the table, said good-by to those I should miss most of all, took up my suit case and departed.

Beside the curb there stood an unhappy-looking taxicab, shivering as with malaria, but the driver showed a face of brazen cheerfulness which, considering the hour and the circumstances, seemed almost indecent. I could not bear his smile. Hastily I blotted him from view beneath a pile of baggage.

With a jerk we started. Few other vehicles disputed our right to the whole width of Seventy-second Street as we skimmed eastward. Farewell, O Central Park! Farewell, O Plaza! And you, Fifth Avenue, empty, gray, deserted now; so soon to flash with fascinating traffic. Farewell! Farewell!

Presently, in that cavern in which vehicles stop beneath the overhanging cliffs of the Grand Central Station, we drew up. A dusky redcap took my baggage. I alighted and, passing through glass doors, gazed down on the vast concourse. Far up in the lofty spaces of the room there seemed to hang a haze, through which—from that amazing and audacious ceiling, painted like[ 8] the heavens—there twinkled, feebly, morning stars of gold. Through three arched windows, towering to the height of six-story buildings, the eastern light streamed softly in, combining with the spaciousness around me, and the blue above, to fill me with a curious sense of paradox: a feeling that I was indoors yet out of doors.

The glass dials of the four-faced clock, crowning the information bureau at the center of the concourse, glowed with electric light, yellow and sickly by contrast with the day which poured in through those windows. Such stupendous windows! Gargantuan spider webs whose threads were massive bars of steel. And suddenly I saw the spider! He emerged from one side, passed nimbly through the center of the web, disappeared, emerged again, crossed the second web and the third in the same way, and was gone—a two-legged spider, walking importantly and carrying papers in his hand. Then another spider came, and still another, each black against the light, each on a different level. For those windows are, in reality, more than windows. They are double walls of glass, supporting floors of glass—layer upon layer of crystal corridor, suspended in the air as by genii out of the Arabian Nights. And through these corridors pass clerks who never dream that they are princes in the modern kind of fairy tale.

As yet the torrent of commuters had not begun to pour through the vast place. The floor lay bare and tawny like the bed of some dry river waiting for the[ 9] melting of the mountain snows. Across the river bed there came a herd of cattle—Italian immigrants, dark-eyed, dumb, patient, uncomprehending. Two weeks ago they had left Naples, with plumed Vesuvius looming to the left; yesterday they had come to Ellis Island; last night they had slept on station benches; to-day they were departing; to-morrow or the next day they would reach their destination in the West. Suddenly there came to me from nowhere, but with a poignance that seemed to make it new, the platitudinous thought that life is at once the commonest and strangest of experiences. What scenes these black, pathetic people had passed through—were passing through! Why did they not look up in wonderment? Why were their bovine eyes gazing blankly ahead of them at nothing? What had dazed them so—the bigness of the world? Yet, after all, why should they understand? What American can understand Italian railway stations? They have always seemed to me to express a sort of mild insanity. But the Grand Central terminal I fancy I do understand. It seems to me to be much more than a successful station. In its stupefying size, its brilliant utilitarianism, and, most of all, in its mildly vulgar grandeur, it seems to me to express, exactly, the city to which it is a gate. That is something every terminal should do unless, as in the case of the Pennsylvania terminal in New York, it expresses something finer. The Grand Central Station is New York, but that classic marvel over there on Seventh[ 10] Avenue is more: it is something for New York to live up to.

When I had bought my ticket and moved along to count my change there came up to the ticket window a big man in a big ulster who asked in a big voice for a ticket to Grand Rapids. As he stood there I was conscious of a most un-New-York-like wish to say to him: "After a while I'm going to Grand Rapids, too!" And I think that, had I said it, he would have told me that Grand Rapids was "some town" and asked me to come in and see him, when I got there,—"at the plant," I think he would have said.

As I crossed the marble floor to take the train I caught sight of my traveling companion leaning rigidly against the wall beside the gate. He did not see me. Reaching his side, I greeted him.

He showed no signs of life. I felt as though I had addressed a waxwork figure.

"Good morning," I repeated, calling him by name.

"I've just finished packing," he said. "I never got to bed at all."

At that moment a most attractive person put in an appearance. She was followed by a redcap carrying a lovely little Russia leather bag. A few years before I should have called a bag like that a dressing case, but watching that young woman as she tripped along with steps restricted by the slimness of her narrow satin skirt, it occurred to me that modes in baggage may have[ 11] changed like those in woman's dress and that her little leather case might be a modern kind of wardrobe trunk.

My companion took no notice of this agitating presence.

"Look!" I whispered. "She is going, too."

Stiffly he turned his head.

"The pretty girl," he remarked, with sad philosophy, "is always in the other car. That's life."

"No," I demurred. "It's only early morning stuff."

And I was right, for presently, in the parlor car, we found our seats across the aisle from hers.

Before the train moved out a boy came through with books and magazines, proclaiming loudly the "last call for reading matter."

I think the radiant being believed him, for she bought a magazine—a magazine of pretty girls and piffle: just the sort we knew she'd buy. As for my companion and me, we made no purchases, not crediting the statement that it was really the "last call." But I am impelled to add that having, later, visited certain book stores of Buffalo, Cleveland, and Detroit, I now see truth in what the boy said.

For a time my companion and I sat and tried to make believe we didn't know that some one was across the aisle. And she sat there and played with pages and made believe she didn't know we made believe. When that had gone on for a time and our train was slipping[ 12] silently along beside the Hudson, we felt we couldn't stand it any longer, so we made believe we wanted to go out and smoke. And as we left our seats she made believe she didn't know that we were going.

Four men were seated in the smoking room. Two were discussing the merits of flannel versus linen mesh for winter underwear. The gentleman who favored linen mesh was a fat, prosperous-looking person, whose gold-rimmed spectacles reflected flying lights from out of doors.

"If you'll wear linen," he declared with deep conviction—"and it wants to be a union suit, too—you'll never go back to shirt and drawers again. I'll guarantee that!" The other promised to try it. Presently I noticed that the first speaker had somehow gotten all the way from linen union suits to Portland, Me., on a hot Sunday afternoon. He said it was the hottest day last year, and gave the date and temperatures at certain hours. He mentioned his wife's weight, details of how she suffered from the heat, the amount of flesh she lost, the name of the steamer on which they finally escaped from Portland to New York, the time of leaving and arrival, and many other little things.

I left him on the dock in New York. A friend (name and occupation given) had met him with a touring car (make and horsepower specified). What happened after that I do not know, save that it was nothing of importance. Important things don't happen to a man like that.

A dusky redcap took my baggage

A dusky redcap took my baggage

Two other men of somewhat Oriental aspect were seated on the leather sofa talking the unintelligible jargon of the factory. But, presently, emerged an anecdote.

"I was going through our sorting room a while back," said the one nearest the window, "and I happened to take notice of one of the girls. I hadn't seen her before. She was a new hand—a mighty pretty girl, with a nice, round figure and a fine head of hair. She kept herself neater than most of them girls do. I says to myself: 'Why, if you was to take that girl and dress her up and give her a little education you wouldn't be ashamed to take her anywheres.' Well, I went over to her table and I says: 'Look at here, little girl; you got a fine head of hair and you'd ought to take care of it. Why don't you wear a cap in here in all this dust?' It tickled her to death to be noticed like that. And, sure enough, she did get a cap. I says to her: 'That's the dope, little girl. Take care of your looks. You'll only be young and pretty like this once, you know.' So one thing led to another, and one day, a while later, she come up to the office to see about her time slip or something, and I jollied her a little. I seen she was a pretty smart kid at that, so—" At that point he lowered his voice to a whisper, and leaned over so that his thick, smiling lips were close to his companion's ear. The motion of the train caused their hat brims to interfere. Disturbed by this, the raconteur removed his derby. His head was absolutely bald.

Well, I am not sure that I should have liked to hear the rest. I shifted my attention back to the apostle of the linen union suit, who had talked on, unremittingly. His conversation had, at least, the merit of entire frankness. He was a man with nothing to conceal.

"Yes, sir!" I heard him declare, "every time you get on to a railroad train you take your life in your hands. That's a positive fact. I was reading it up just the other day. We had almost sixteen thousand accidents to trains in this country last year. A hundred and thirty-nine passengers killed and between nine and ten thousand injured. That's not counting employees, either—just passengers like us." He emphasized his statements by waving a fat forefinger beneath the listener's nose, and I noticed that the latter seemed to wish to draw his head back out of range, as though in momentary fear of a collision.

For my part, I did not care for these statistics. They were not pleasant to the ears of one on the first leg of a long railroad journey. I rose, aimed the end of my cigar at the convenient nickel-plated receptacle provided for that purpose by the thoughtful Pullman Company, missed it, and retired from the smoking room. Or, rather, I emerged and went to luncheon.

Our charming neighbor of the parlor car was already in the diner. She finished luncheon before we did, and, passing by our table as she left, held her chin well up and kept her eyes ahead with a precision almost military—almost, but not quite. Try as she would, she was[ 15] unable to control a slight but infinitely gratifying flicker of the eyelids, in which nature triumphed over training and femininity defeated feministic theory.

A little later, on our way back to the smoking room, we saw her seated, as before, behind the sheltering ramparts of her magazine. This time it pleased our fancy to take the austere military cue from her. So we filed by in step, as stiff as any guardsmen on parade before a princess seated on a green plush throne. Resolutely she kept her eyes upon the page. We might have thought she had not noticed us at all but for a single sign. She uncrossed her knees as we passed by.

In the smoking room we entered conversation with a young man who was sitting by the window. He proved to be a civil engineer from Buffalo. He had lived in Buffalo eight years, he said, without having visited Niagara Falls. ("I've been meaning to go, but I've kept putting it off.") But in New York he had taken time to go to Bedloe Island and ascend the Statue of Liberty. ("It's awfully hot in there.") Though my companion and myself had lived in New York for many years, neither of us had been to Bedloe Island. But both of us had visited the Falls. The absurd humanness of this was amusing to us all; to my companion and me it was encouraging as well, for it seemed to give us ground for hope that, in our visits to strange places, we might see things which the people living in those places fail to see.

When, after finishing our smoke, we went back to[ 16] our seats, the being across the way began to make believe to read again. But now and then, when some one passed, she would look up and make believe she wished to see who it might be. And always, after doing so, she let her eyes trail casually in our direction ere they sought the page again. And always we were thankful.

As the train slowed down for Rochester we saw her rise and get into her slinky little coat. The porter came and took her Russia leather bag. Meanwhile we hoped she would be generous enough to look once more before she left the car. Only once more!

But she would not. I think she had a feeling that frivolity should cease at Rochester; for Rochester, we somehow sensed, was home to her. At all events she simply turned and undulated from the car.

That was too much! Enough of make-believe! With one accord we swung our chairs to face the window. As she appeared upon the platform our noses almost touched the windowpane and our eyes sent forth forlorn appeals. She knew that we were there, yet she walked by without so much as glancing at us.

We saw a lean old man trot up to her, throw one arm about her shoulders, and kiss her warmly on the cheek. Her father—there was no mistaking that. They stood there for a moment on the platform talking eagerly; and as they talked they turned a little bit, so that we saw her smiling up at him.

Then, to our infinite delight, we noticed that her eyes were slipping, slipping. First they slipped down to her

What scenes these black, pathetic people had passed through—were passing

through! Why did they not look up in wonderment?

What scenes these black, pathetic people had passed through—were passing

through! Why did they not look up in wonderment?

[ 17] father's necktie. Then sidewise to his shoulder, where they fluttered for an instant, while she tried to get them under control. But they weren't the kind of eyes which are amenable. They got away from her and, with a sudden leap, flashed up at us across her father's shoulder! The minx! She even flung a smile! It was just a little smile—not one of her best—merely the fragment of a smile, not good enough for father, but too good to throw away.

Well—it was not thrown away. For it told us that she knew our lives had been made brighter by her presence—and that she didn't mind a bit.

Pushing on toward Buffalo as night was falling, my companion and I discussed the fellow travelers who had most engaged our notice: the young engineer from Buffalo, keen and alive, with a quick eye for the funny side of things; the hairless amorist; the genial bore, whose wife (we told ourselves) got very tired of him sometimes, but loved him just because he was so good; the pretty girl, who couldn't make her eyes behave because she was a pretty girl. We guessed what kind of house each one resided in, the kind of furniture they had, the kind of pictures on the walls, the kind of books they read—or didn't read. And I believed that we guessed right. Did we not even know what sort of underwear encased the ample figure of the man with the amazing memory of unessential things? And, while[ 18] touching on this somewhat delicate subject, were we not aware that if the alluring being who left the train, and us, at Rochester possessed the once-so-necessary garment called a petticoat, that petticoat was hanging in her closet?

All this I mention because the thought occurred to me then (and it has kept recurring since) that places, no less than persons, have characters and traits and habits of their own. Just as there are colorless people there are colorless communities. There are communities which are strong, self-confident, aggressive; others lazy and inert. There are cities which are cultivated; others which crave "culture" but take "culturine" (like some one drinking from the wrong bottle); and still others almost unaware, as yet, that esthetic things exist. Some cities seem to fairly smile at you; others are glum and worried like men who are ill, or oppressed with business troubles. And there are dowdy cities and fashionable cities—the latter resembling one another as fashionable women do. Some cities seem to have an active sense of duty, others not. And almost all cities, like almost all people, appear to be capable alike of baseness and nobility. Some cities are rich and proud like self-made millionaires; others, by comparison, are poor. But let me digress here to say that, though I have heard mention of "hard times" at certain points along my way, I don't believe our modern generation knows what hard times really are. To most Americans the term appears to signify that life is hard indeed on[ 19] him who has no motor car or who goes without champagne at dinner.

My contacts with many places and persons I shall mention in the following chapters have, of necessity, been brief. I have hardly more than glimpsed them as I glimpsed those fellow travelers on the train. Therefore I shall merely try to give you some impressions, from a sort of mental sketchbook, of the things which I have seen and done and heard. There is one point in particular about that sketchbook: in it I have reserved the right to set down only what I pleased. It has been hard to do that sometimes. People have pulled me this way and that, telling me what to see and what not to see, what to write and what to leave out. I have been urged, for instance, to write about the varied industries of Cleveland, the parks of Milwaukee, and the enormous red apples of Louisiana, Mo. I may come to the apples later on, for I ate a number of them and enjoyed them; but the varied industries of Cleveland and the Milwaukee parks I did not eat.

I claim the further right to ignore, when I desire to, the most important things, or to dwell with loving pen upon the unimportant. Indeed, I reserve all rights—even to the right to be perverse.

Thus I shall mention things which people told me not to mention: the droll Detroit Art Museum; the comic chimney rising from the center of a Grand Rapids park; horrendous scenes in the Chicago stockyards; the Free[ 20] Bridge, standing useless over the river at St. Louis for want of an approach; the "wettest block"—a block full of saloons, which marks the dead line between "wet" Kansas City, Mo., and "dry" Kansas City, Kas. (I never heard about that block until a stranger wrote and told me not to mention it.)

As for statistics, though I have been loaded with them to the point of purchasing another trunk, I intend to use them as sparingly as possible. And every time I use them I shall groan.[ 21]

Alighting from the train at Buffalo, I was reminded of my earlier reflection that railway stations should express their cities. In Buffalo the thought is painful. If that city were in fact, expressed by its present railway stations, people would not get off there voluntarily; they would have to be put off. And yet, from what I have been told, the curious and particularly ugly relic which is the New York Central Station there, to-day, does tell a certain story of the city. Buffalo has long been torn by factional quarrels—among them a protracted fight as to the location of a modern station for the New York Central Lines. The East Side wants it; the West Side wants it. Neither has it. The old station still stands—at least it was standing when I left Buffalo, for I was very careful not to bump it with my suit case.

This difference of opinion between the East Side and the West with regard to the placing of a station is, I am informed, quite typical of Buffalo. Socially, commercially, religiously, politically, the two sides disagree. The dividing line between them, geographically, is not, as might be supposed, Division Street. (That, by the[ 22] way, is a peculiarity of highways called "Division Street" in most cities—they seldom divide anything more important than one row of buildings from another.) The real street of division is called Main.

Main Street! How many American towns and cities have used that name, and what a stupid name it is! It is as characterless as a number, and it lacks the number's one excuse for being. If names like Tenth Street or Eleventh Avenue fail to kindle the imagination they do not fail, at all events, to help the stranger find his way—although it should be added that strangers do, somehow, manage to find their way about in London, Paris, and even Boston, where the modern American system of numbering streets and avenues is not in vogue. But I am not agitating against the numbering of streets. Indeed, I fear I rather believe in it, as I believe in certain other dull but useful things like work and government reports. What I am crying out about is the stupid naming of such streets as carry names. Why do we have so many Main Streets? Do you think we lack imagination? Then look at the names of Western towns and Kansas girls and Pullman cars! The thing is an enigma.

Main Street is not only a bad name for a thoroughfare; the quality which it implies is unfortunate. And that quality may be seen in Main Street, Buffalo. On an exaggerated scale that street is like the Main Street of a little town, for the business district, the retail shopping district, all the city's activities string along on

We made believe we wanted to go out and smoke. And as we left

our seats she made believe she didn't know that we were going

We made believe we wanted to go out and smoke. And as we left

our seats she made believe she didn't know that we were going

either side. It is bad for a city to grow in that elongated way just as it is bad for a human being. To either it imparts a kind of gawky awkwardness.

The development of Main Street, Buffalo, has been natural. That is just the trouble; it has been too natural. Originally it was the Iroquois trail; later the route followed by the stages coming from the East. So it has grown up from log-cabin days. It is a fine, broad street; all that it lacks is "features." It runs along its wide, monotonous way until it stops in the squalid surroundings of the river; and if the river did not happen to be there to stop it, it would go on and on developing, indefinitely, and uninterestingly, in that direction as well as in the other.

The thing which Buffalo lacks physically is a recognizable center; a point at which a stranger would stop, as he stops in Piccadilly Circus or the Place de l'Opéra, and say to himself with absolute assurance: "Now I am at the very heart of the city." Every city ought to have a center, and every center ought to signify in its spaciousness, its arrangement and its architecture, a city's dignity. Buffalo is, unfortunately, far from being alone in her need of such a thing. Where Buffalo is most at fault is that she does not even seem to be thinking of municipal distinction. And very many other cities are. Cleveland is already attaining it in a manner which will be magnificent; Chicago has long planned and is slowly executing; Denver has work upon a splendid municipal center well under way; so has San[ 24] Francisco; St. Louis, Milwaukee, and Grand Rapids have plans for excellent municipal improvements. Even St. Paul is waking up and widening an important business street.

Every one knows that what is called "a wave of reform" has swept across the country, but not every one seems to know that there is also surging over the United States a "wave" of improved public taste. I shall write more of this later. Suffice it now to say that it manifests itself in countless forms: in municipal improvements of the kind of which the Cleveland center is, perhaps, the best example in the country; in architecture of all classes; in household furniture and decoration; in the tendency of art museums to realize that modern American paintings are the finest modern paintings obtainable in the world to-day; in the tendency of private art collectors not to buy quite so much rubbish as they have bought in the past; in the Panama-Pacific Exposition, which will be the most beautiful exposition anybody ever saw; and in innumerable other ways. Indeed, public taste in the United States has, in the last ten years, taken a leap forward which the mind of to-day cannot hope to measure. The advance is nothing less than marvelous, and it is reflected, I think, in every branch of art excepting one: the literary art, which has in our day, and in our country, reached an abysmal depth of degradation.

With Cleveland so near at hand as an example, and[ 25] so many other American cities thinking about civic beauty, Buffalo ought soon to begin to rub her eyes, look about, and cast up her accounts. Perhaps her trouble is that she is a little bit too prosperous with an olden-time prosperity; a little bit too somnolent and satisfied. There is plenty to eat; business is not so bad; there are good clubs, and there is a delightful social life and a more than ordinary degree of cultivation. Furthermore, there may be a new station for the New York Central some day, for it is a fact that there are now some street cars which actually cross Main Street, instead of stopping at the Rubicon and making passengers get out, cross on foot, and take the other car on the other side! That, in itself, is a startling state of things. Evidently all that is needed now is an earthquake.

I have remarked before that cities, like people, have habits. Just as Detroit has the automobile habit, Pittsburgh the steel habit, Erie, Pa., the boiler habit, Grand Rapids the furniture habit, and Louisville the (if one may say so) whisky habit, Buffalo had in earlier times the transportation habit. The first fortunes made in Buffalo came originally from the old Central Wharf, where toll was taken of the passing commerce. Hand in hand with shipping came that business known by the unpleasant name of "jobbing." From the opening of the Erie Canal until the late seventies, jobbing flourished in Buffalo, but of recent years[ 26] her jobbing territory has diminished as competition with surrounding centers has increased.

The early profits from docks and shipping were considerable. The business was easy; it involved comparatively small investment and but little risk. So when, with the introduction of through bills of lading, this business dwindled, it was hard for Buffalo to readjust herself to more daring ventures, such as manufacturing. "For," as a Buffalo man remarked to me, "there is only one thing more timid than a million dollars, and that is two million." It was the same gentleman, I think, who, in comparing the Buffalo of to-day with the Buffalo of other days, called my attention to the fact that not one man in the city is a director of a steam railroad company.

From her geographical position with regard to ore, limestone, and coal it would seem that Buffalo might well become a great iron and steel city like Cleveland, but for some reason her ventures in this direction have been unfortunate. One steel company in which Buffalo money was invested, failed; another has been struggling along for some years and has not so far proved profitable. Some Buffalonians made money in a land boom a dozen or so years since; then came the panic, and the boom burst with a loud report, right in Buffalo's face.

Back of most of this trouble there seems to have been a streak of real ill luck.

The gentleman who favored linen mesh was a fat, prosperous-looking person,

whose gold-rimmed spectacles reflected flying lights from out of doors

The gentleman who favored linen mesh was a fat, prosperous-looking person,

whose gold-rimmed spectacles reflected flying lights from out of doors

There is a great deal of money in Buffalo, but it is wary money—financial wariness seems to be another Buffalo habit. And there are other cities with the same characteristic. You can tell them because, when you begin to ask about various enterprises, people will say: "No, we haven't this and we haven't that, but this is a safe town in times of financial panic." That is what they say in Buffalo; they also say it in St. Louis and St. Paul. But if they say it in Chicago, or Minneapolis, or Kansas City, or in those lively cities of the Pacific slope, I did not hear them. Those cities are not worrying about financial panics which may come some day, but are busy with the things which are.

If you ask a Buffalo man what is the matter with his city, he will, very likely, sit down with great solemnity and try to tell you, and even call a friend to help him, so as to be sure that nothing is overlooked. He may tell you that the city lacks one great big dominating man to lead it into action; or that there has been, until recently, lack of coöperation between the banks; or that there are ninety or a hundred thousand Poles in the city and only about the same number of people springing from what may be called "old American stock." Or he may tell you something else.

If, upon the other hand, you ask a Minneapolis man that question, what will he do? He will look at you pityingly and think you are demented. Then he will tell you very positively that there is nothing the matter with Minneapolis, but that there is something definitely the matter with any one who thinks there is! Yes, in[ 28]deed! If you want to find out what is the matter with Minneapolis, it is still necessary to go for information to St. Paul. As you proceed westward, such a question becomes increasingly dangerous.

Ask a Kansas City man what is wrong with his town and he will probably attack you; and as for Los Angeles—! Such a question in Los Angeles would mean the calling out of the National Guard, the Chamber of Commerce, the Rotary Club, and all the "boosters" (which is to say the entire population of the city); the declaring of martial law, a trial by summary court-martial, and your immediate execution. The manner of your execution would depend upon the phrasing of your question. If you had asked: "Is there anything wrong with Los Angeles?" they'd probably be content with selling you a city lot and then hanging you; but if you said: "What is wrong with Los Angeles?" they would burn you at the stake and pickle your remains in vitriol.

At this juncture I find myself oppressed with the idea that I haven't done Buffalo justice. Also, I am annoyed to discover that I have written a great deal about business. When I write about business I am almost certain to be wrong. I dislike business very much—almost as much as I dislike politics—and the idea of infringing upon the field of friends of mine like Lincoln Steffens, Ray Stannard Baker, Miss Tarbell, Samuel Hopkins Adams, Will Irwin, and others,[ 29] is extremely distasteful to me. But here is the trouble: so many writers have run a-muckraking that, now-a-days, when a writer appears in any American city, every one assumes that he is scouting around in search of "shame." The result is that you don't have to hunt for shame. People bring it to you by the cartload. They don't give you time to explain that you aren't a shame collector—that you don't even know a good piece of shame when you see it—they just drive up, dump it at your door, and go back to get another load.

My companion and I were new at the game in Buffalo. As the loads of shame began to arrive, we had a feeling that something was going wrong with our trip. We had come in search of cheerful adventure, yet here we were barricaded in by great bulwarks of shame. In a few hours there was enough shame around us to have lasted all the reformers and muckrakers I know a whole month. We couldn't see over the top of it. It hypnotized us. We began to think that probably shame was what we wanted, after all. Every one we met assumed it was what we wanted, and when enough people assume a certain thing about you it is very difficult to buck against them. By the second day we had ceased to be human and had begun to act like muckrakers. We became solemn, silent, mysterious. We would pick up a piece of shame, examine it, say "Ha!" and stick it in our pockets. When some white-faced Buffalonian would drive up with another load of shame I would go up to him, wave my finger under his nose and, trying to[ 30] look as much like Steffens as I could, say in a sepulchral voice: "Come! Out with it! What are you holding back? Tell me all! Who tore up the missing will?" Then that poor, honest, terrified Buffalonian would gasp and try to tell me all, between his chattering teeth. And when he had told me all I would continue to glare at him horribly, and ask for more. Then he would begin making up stories, inventing the most frightful and shocking lies so as not to disappoint me. I would print some of them here, but I have forgotten them. That is the trouble with the amateur muckraker or reformer. His mind isn't trained to his work. He is constantly allowing it to be diverted by some pleasant thing.

For instance, some one pointed out to me that the water front of the city, along the Niagara River, is so taken up by the railroads that the public does not get the benefit of that water life which adds so much to the charm of Cleveland and Detroit. That situation struck me as affording an excellent piece of muck to rake. For isn't it always the open season so far as railroads are concerned?

I ought to have kept my mind on that, but in my childlike way I let myself go ambling off through the parks. I found the parks delightful, and in one of them I came upon a beautiful Greek temple, built of marble and containing a collection of paintings of which any city should be proud. Now that is a disconcerting sort of thing to find when you have just abandoned your[ 31]self to the idea of becoming a muckraker! How can you muckrake a gallery like that? It can't be done.

With the possible exception of the Chicago Art Institute my companion and I did not see, upon our entire journey, any gallery of art in which such good judgment had been shown in the selection of paintings as in the Albright Gallery in Buffalo. Though the Chicago Art Institute is much the larger and richer museum, and though its collection is more comprehensive, its modern art is far more heterogeneous than that of Buffalo. One admires that Albright Gallery not only for the paintings which hang upon its walls, but also for those which do not hang there. Judgment has been shown not only in selecting paintings, but (one concludes) in rejecting gifts. I do not know that the Albright Gallery has rejected gifts, but I do know that the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Chicago Art Institute have, at times, failed to reject gifts which should have been rejected. Almost all museums fail in that respect in their early days. When a rich man offers a bad painting, or a roomful of bad paintings, the museum is afraid to say "No," because rich men must be propitiated. That has been the curse of art museums; they have to depend on rich men for support. And rich men, however generous they may be, and however much they may be interested in art, are, for the most part, lacking in any true and deep under[ 32]standing of it. That is one trouble with being rich—it doesn't give you time to be much of anything else. If rich men really did know art, there would not be so many art dealers, and so many art dealers would not be going to expensive tailors and riding in expensive limousines.

Those who control the Albright Gallery have been wise enough to specialize in modern American painting. They have not been impressed, as so many Americans still are impressed, by the sound of the word "Europe." Nor have they attempted to secure old masters.

Does it not seem a mistake for any museum not possessed of enormous wealth to attempt a collection of old masters? A really fine example of the work of an old master ties up a vast amount of money, and, however splendid it may be, it is only one canvas, after all; and one or two or three old masters do not make a representative collection. Rather, it seems to me, they tend to disturb balance in a small museum.

To many American ears "Europe" is still a magic word. It makes little difference that Europe remains the happy hunting ground of the advanced social climber; but it makes a good deal of difference that so many American students of the arts continue to believe that there is some mystic thing to be gotten over there which is unobtainable at home. Europe has done much for us and can still do much for us, but we must learn not to accept blindly as we have in the past. Until quite recently, American art museums did, for the most part,[ 33] buy European art which was in many instances absolutely inferior to the art produced at home. And unless I am very much mistaken a third-rate portrait painter, with a European name (and a clever dealer to push him) can still come over here and reap a harvest of thousands while Americans with more ability are making hundreds.

In a few hours there was enough shame around us to have lasted all the reformers and muckrakers

I know a whole month

In a few hours there was enough shame around us to have lasted all the reformers and muckrakers

I know a whole month

One of the brightest signs for American painting to-day is the fact that it is now found profitable to make and sell forgeries of the works of our most distinguished modern artists—even living ones. This is a new and encouraging situation. A few years ago it was hardly worth a forger's time to make, say, a false Hassam, when he might just as well be making a Corot—which reminds me of an amusing thing a painter said to me the other day.

We were passing through an art gallery, when I happened to see at the end of one room three canvases in the familiar manner of Corot.

"What a lot of Corots there are in this country," I remarked.

"Yes," he replied. "Of the ten thousand canvases painted by Corot, there are thirty thousand in the United States."

There are two interesting hotels in Buffalo. One, the Iroquois, is characterized by a kind of solid dignity and has for years enjoyed a high reputation. It is patronized to-day at luncheon time by many of[ 34] Buffalo's leading business men. Another, the Statler, is more "commercial" in character. My companion and I happened to stop at the latter, and we became very much interested in certain things about it. For one thing, every room in the hotel has running ice water and a bath—either a tub or a shower. Everywhere in that hotel we saw signs. At the desk, when we entered, hung a sign which read: Clerk on duty, Mr. Pratt.

There were signs in our bedrooms, too. I don't remember all of them, but there was one bearing the genial invitation: Criticize and suggest for the improvement of our service. Complaint and suggestion box in lobby.

While I was in that hotel I had nothing to "criticize and suggest," but I have been in other hotels where, if such an invitation had been extended to me, I should have stuffed the box.

Besides the signs, we found in each of our rooms the following: a clothes brush; a card bearing on one side a calendar and on the other side a list of all trains leaving Buffalo, and their times of departure; a memorandum pad and pencil by the telephone; a Bible ("Placed in this hotel by the Gideons"), and a pincushion, containing not only a variety of pins (including a large safety pin), but also needles threaded with black thread and white, and buttons of different kinds, even to a suspender button.

But aside from the prompt service we received, I think the thing which pleased us most about that hotel

My companion and I made excuses to go downstairs and wash

our hands in the public washroom, just for the pleasure of doing

so without fear of being attacked by a swarthy brigand with

a brush

My companion and I made excuses to go downstairs and wash

our hands in the public washroom, just for the pleasure of doing

so without fear of being attacked by a swarthy brigand with

a brush

[ 35] was a large sign in the public wash room, downstairs. Had I come from the West I am not sure that sign would have startled me so much, but coming from New York—! Well, this is what it said:

Believing that voluntary service in washrooms is distasteful to guests, attendants are instructed to give no service which the guest does not ask for.

Time and again, while we were in Buffalo, my companion and I made excuses to go downstairs and wash our hands in the public washroom, just for the pleasure of doing so without fear of being attacked by a swarthy brigand with a brush. We became positively fond of the melancholy washroom boy in that hotel. There was something pathetic in the way he stood around waiting for some one to say: "Brush me!" Day after day he pursued his policy of watchful waiting, hoping against hope that something would happen—that some one would fall down in the mud and really need to be brushed; that some one would take pity on him and let himself be brushed anyhow. The pathos of that boy's predicament began to affect us deeply. Finally we decided, just before leaving Buffalo, to go downstairs and let him brush us. We did so. When we asked him to do it he went very white at first. Then, with a glad cry, he leaped at us and did his work. It was a real brushing we got that day—not a mere slap on the back with a whisk broom, meaning "Stand and deliver!" but the kind of brushing[ 36] that takes the dust out of your clothes. The wash room was full of dust before he got through. Great clouds of it went floating up the stairs, filling the hotel lobby and making everybody sneeze. When he finished we were renovated. "How much do you think we ought to give him for all this?" I asked of my companion.

"If the conventional dime which we give the washroom boys in New York hotels," he replied, "is proper payment for the services they render, I should say we ought to give this boy about twenty-seven dollars."

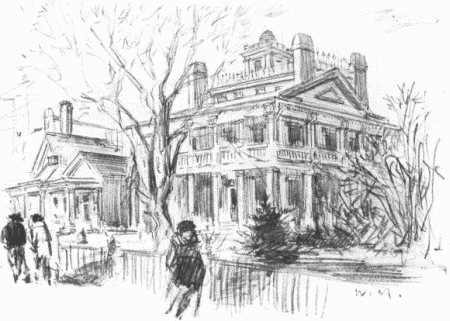

There are many other things about Buffalo which should be mentioned. There is the Buffalo Club—the dignified, solid old club of the city; and there is the Saturn Club, "where women cease from troubling and the wicked are at rest." And there is Delaware Avenue, on which stand both these clubs, and many of the city's finest homes.

Unlike certain famous old residence streets in other cities, Delaware Avenue still holds out against the encroachments of trade. It is a wide, fine street of trees and lawns and residences. Despite the fact that many of its older houses are of the ugly though substantial architecture of the sixties, seventies, and eighties, and many of its newer ones lack architectural distinction, the general effect of Delaware Avenue is still fine and American.

My impression of this celebrated street was neces[ 37]sarily hurried, having been acquired in the course of sundry dashes down its length in motor cars. I recall a number of its buildings only vaguely now, but there is one which I admired every time I saw it, and which still clings in my memory both as a building and as a sermon on the enduring beauty of simplicity and good, old-fashioned lines—the office of Spencer Kellogg & Sons, at the corner of Niagara Square.

It happened that just before we left New York there was a newspaper talk about some rich women who had organized a movement of protest against the ever-increasing American tendency toward show and extravagance. We were, therefore, doubly interested when we heard of a similar activity on the part of certain fashionable women of Buffalo.

Our hostess at a dinner party there was the first to mention it, but several other ladies added details. They had formed a few days before a society called the "Simplicity League," the members of which bound themselves to give each other moral support in their efforts to return to a more primitive mode of life. I cannot recall now whether the topic came up before or after the butler and the footman came around with caviar and cocktails, but I know that I had learned a lot about it from charming and enthusiastic ladies at either side of me before the sherry had come on; that, by the time the sauterne was served, I was deeply impressed, and that,[ 38] with the roast and the Burgundy, I was prepared to take the field against all comers, not only in favor of simplicity, but in favor of anything and everything which was favored by my hostess. Throughout the salad, the ices, the Turkish coffee, and the Corona-coronas I remained her champion, while with the port—ah! nothing, it seems to me, recommends the old order of things quite so thoroughly as old port, which has in it a sermon and a song. After dinner the ladies told us more about their league.

"We don't intend to go to any foolish extremes," said one who looked like the apotheosis of the Rue de la Paix. "We are only going to scale things down and eliminate waste. There is a lot of useless show in this country which only makes it hard for people who can't afford things. And even for those who can, it is wrong. Take the matter of dress—a dress can be simple without looking cheap. And it is the same with a dinner. A dinner can be delicious without being elaborate. Take this little dinner we had to-night—"

"What?" I cried.

"Yes," she nodded. "In future we are all going to give plain little dinners like this."

"Plain?" I gasped.

Our hostess overheard my choking cry.

"Yes," she put in. "You see, the league is going to practise what it preaches."

"But I didn't think it had begun yet! I thought this dinner was a kind of farewell feast—that it was—"

I was prepared to take the field against all comers, not only in favor of

simplicity, but in favor of anything and everything which was favored by

my hostess

I was prepared to take the field against all comers, not only in favor of

simplicity, but in favor of anything and everything which was favored by

my hostess

Our hostess looked grieved. The other ladies of the league gazed at me reproachfully.

"Why!" I heard one exclaim to another, "I don't believe he noticed!"

"Didn't you notice?" asked my hostess.

I was cornered.

"Notice?" I asked. "Notice what?"

"That we didn't have champagne!" she said.[ 40]

Before leaving home we were presented with a variety of gifts, ranging all the way from ear muffs to advice. Having some regard for the esthetic, we threw away the ear muffs, determining to buy ourselves fur caps when we should need them. But the advice we could not throw away; it stuck to us like a poor relation.

In the parlor car, on the way from Buffalo to Cleveland, our minds got running on sad subjects.

"We have come out to find interesting things—to have adventures," said my blithe companion. "Now supposing we go on and on and nothing happens. What will we do then? The publishers will have spent all this money for our traveling, and what will they get?"

I told him that, in such an event, we would make up adventures.

"What, for instance?" he demanded.

I thought for a time. Then I said:

"Here's a good scheme—we could begin now, right here in this car. You act like a crazy man. I will be your keeper. You run up and down the aisle shouting—talk wildly to these people—stamp on your hat[ 41]—do anything you like. It will interest the passengers and give us something nice to write about. And you could make a picture of yourself, too."

Instead of appreciating that suggestion he was annoyed with me, so I ventured something else.

"How would it be for you to beat a policeman on the helmet?"

He didn't care for that either.

"Why don't you think of something for yourself to do?" he said, somewhat sourly.

"All right," I returned. "I'm willing to do my share. I will poison you and get arrested for it."

"If you do that," he criticized, "who will make the pictures?"

I saw that he was in a humor to find fault with anything I proposed, so I let him ramble on. He had a regular orgy of imaginary disaster, running all the way from train wrecks, in which I was killed and he was saved only to have the bother and expense of shipping my remains home, to fires in which my notebooks were burned up, leaving on his hands a lot of superb but useless drawings.

After a time he suggested that we make up a list of the things we had been warned of. I did not wish to do it, but, acting on the theory that fever must run its course, I agreed, so we took paper and pencil and began. It required about two hours to get everything down, beginning with Aches, Actresses, Adenoids, Alcoholism, Amnesia, Arson, etc., and running on, through the[ 42] alphabet to Zero weather, Zolaism, and Zymosis.

After looking over the category, my companion said:

"The trouble with this list is that it doesn't present things in the order in which they may reasonably be expected to occur. For instance, you might get zymosis, or attempt to write like Zola, at almost any time, yet those two dangers are down at the bottom of the list. On the other hand, things like actresses, alcoholism, and arson seem remote. We must rearrange."

I thought it wise to give in to him, so we set to work again. This time we made two lists: one of general dangers—things which might overtake us almost anywhere, such as scarlet fever, hardening of the arteries, softening of the brain, and "road shows" from the New York Winter Garden; another arranged geographically, according to our route. Thus, for example, instead of listing Elbert Hubbard under the letter "H," we elevated him to first place, because he lives near Buffalo, which was our first stop.

I didn't want to put down Hubbard's name at all—I thought it would please him too much if he ever heard about it. I said to my companion:

"We have already passed Buffalo. And, besides, there are some things which the instinct of self-preservation causes one to recollect without the aid of any list."

"I know it," he returned, stubbornly, "but, in the interest of science, I wish this list to be complete."

So we put down everything: Elbert Hubbard,

Chamber of Commerce representatives were with us

all the first day and until we went to our rooms, late

at night

Chamber of Commerce representatives were with us

all the first day and until we went to our rooms, late

at night

[ 43] Herbert Kaufman, Eva Tanguay, Upton Sinclair, and all.

A few selected items from our geographical list may interest the reader as giving him some idea of the locations of certain things we had to fear. For example, west of Chicago we listed Oysters, and north of Chicago Frozen Ears and Frozen Noses—the latter two representing the dangers of the Minnesota winter. So our list ran on until it reached the point where we would cross the Great Divide, at which place the word "Boosters" was writ large.

I recall now that, according to our geographical arrangement, there wasn't much to be afraid of until we got beyond Chicago, and that the first thing we looked forward to with real dread was the cold in Minnesota. We dreaded it more than arson, because if some one sets fire to your ear or your nose, you know it right away, and can send in an alarm; but cold is sneaky. It seems, from what they say, that you can go along the street, feeling perfectly well, and with no idea that anything is going wrong with you, until some experienced resident of the place touches you upon the arm and says: "Excuse me, sir, but you have dropped something." Then you look around, surprised, and there is your ear, lying on the sidewalk. But that is not the worst of it. Before you can thank the man, or pick your ear up and dust it off, some one will very likely come along and step on it. I do not think they do it purposely; they are simply careless about where they walk. But whether it happens by[ 44] accident or design, whether the ear is spoiled or not, whether or not you be wearing your ear at the time of the occurrence—in any case there is something exceedingly offensive, to the average man, in the idea of a total stranger's walking on his ear.

I mention this to point a moral. However prepared we may be, in life, we are always unprepared. However informed we may be, we are always uninformed. We gaze up at the sky, dreading to-morrow's rain, and slip upon to-day's banana peel. We move toward Cleveland dreading the Minnesota winter which is yet far off, having no thought of the "booster," whom we believe to be still farther off. And what happens? We step from the train, all innocent and trusting, and then, ah, then——!

If it be true, indeed, that the "booster" flourishes more furiously the farther west you find him, let me say (and I say it after having visited California, Oregon, and Washington) that Cleveland must be newly located upon the map. For, if "boosting" be a western industry, Cleveland is not an Ohio city, nor even a Pacific Slope city, but is an island out in the midst of the Pacific Ocean.

Nor is this a mere opinion of my own. Upon the mastodonic brow of the Cleveland Chamber of Commerce there hangs an official laurel wreath. The New York Bureau of Municipal Research invited votes from the secretaries of Chambers of Commerce and similar or[ 45]ganizations in thirty leading cities, as to which of these bodies had accomplished most for its city, industrially, commercially, etc. Cleveland won.

No one who has caromed against the Cleveland Chamber of Commerce will wonder that Cleveland won. All other Chambers of Commerce I have met, sink into desuetude and insignificance when compared with that of Cleveland. Where others merely "boost," Cleveland "boosts" intensively. She can raise more bushels of statistics to the acre than other cities can quarts. And the more Cleveland statistics you hear, the more you become amazed that you do not live there. It seems reckless not to do so. The Cleveland Chamber of Commerce can prove this to you not merely with figures, but also with figures of speech.

Take the matter of population. Everybody knows that Cleveland is the "Sixth City" in the United States, but not everybody knows that in 1850 she was forty-third. The Chamber of Commerce told me that, but I have prepared some figures of my own which will, perhaps, give the reader some idea of Cleveland's magnitude. Cleveland is only a little smaller than Prague, while she has about 50,000 more people than Breslau.

If that does not impress you with the city's size, listen to this: Cleveland is actually twice as great, in population, as either Nagoya or Riga! Who would have believed it? The thing seems incredible! I never dreamed that such a situation existed until I looked it up in the "World Almanac." And some day, when I[ 46] have more time, I intend to look up Nagoya and Riga in the atlas and find out where they are.

A Chamber of Commerce booklet gives me the further information that "Cleveland is the fifth American city in manufactures, and that she comes first in the manufacture of steel ships, heavy machinery, wire and wire nails, bolts and nuts, vapor stoves, electric carbons, malleable castings, and telescopes"—a list which, by the way, sounds like one of Lewis Carroll's compilations.

The information that Cleveland is also the first city in the world in its record, per capita, for divorce, does not come to me from the Chamber of Commerce booklet—but probably the fact was not known when the booklet was printed.

Besides being first in so many interesting fields, Cleveland is the second of the Great Lake cities, and is also second in "the value of its product of women's outer wearing apparel and fancy knit goods."

It is, furthermore, "the cheapest market in the North for pig iron."

It is an Elizabethan building, with a heavy timbered

front, suggesting some ancient, hospitable, London coffee

house where wits of old were used to meet

It is an Elizabethan building, with a heavy timbered

front, suggesting some ancient, hospitable, London coffee

house where wits of old were used to meetThere are other figures I could give (saving myself a lot of trouble, at the same time, because I only have to copy them from a book), but I want to stop and let that pig-iron statement sink into you as it sank into me when I first read it. I wonder if you knew it before? I am ashamed to admit it, but I did not. I didn't consider where I could get my pig iron the cheapest. When I wanted pig iron I simply went out and bought it, at the nearest place, right in New York. That is, I bought it in New York unless I happened to be traveling when the craving came upon me. In that case I would buy a small supply wherever I happened to be—just enough to last me until I could get home again. I don't know how pig iron affects you, but with me it acts peculiarly. Sometimes I go along for weeks without even thinking of it; then, suddenly, I feel that I must have some at once—even if it is the middle of the night. Of course a man doesn't care what he pays for his pig iron when he feels like that. But in my soberer moments I now realize that it is best to be economical in such matters. The wisest plan is to order enough pig iron from Cleveland to keep you for several months, being careful to notice when the supply is running low, so that you can order another case.

Apropos of this let me say here, in response to many inquiries as to what the nature of this work of mine would be, that I intend it to be "useful as well as ornamental"—to quote the happy phrase, coined by James Montgomery Flagg. That is, I intend not only to entertain and instruct the reader but, where opportunity offers, to give him the benefit of good sound advice, such as I have just given with regard to the purchasing of pig iron.[ 48]

Because I have told you so much about the Chamber of Commerce you must not assume that the Chamber of Commerce was with us constantly while we were in Cleveland, for that is not the case. True, Chamber of Commerce representatives were with us all the first day and until we went to our rooms, late at night. But at our rooms they left us, merely taking the precaution to lock us in. No attempt was made to assist us in undressing or to hear our prayers or tuck us into bed. Once in our rooms we were left to our own devices. We were allowed to read a little, if we wished, to whisper together, or even to amuse ourselves by playing with the fixtures in the bathroom.

On the morning of the second day they came and let us out, and took us to see a lot of interesting and edifying sights, but by afternoon they had acquired sufficient confidence in us to turn us loose for a couple of hours, allowing us to roam about, at large, while they attended to their mail.

We made use of the freedom thus extended to us by presenting several letters of introduction to Cleveland gentlemen, who took us to various clubs.[ 49]

Almost every large city in the country has one solid, dignified old club, occupying a solid, dignified old building on a corner near the busy part of town. The building is always recognizable, even to a stranger. It suggests a fine cuisine, an excellent wine cellar, and a great variety of good cigars in prime condition. In the front of such a club there are large windows of plate glass, back of which the passer-by may catch a glimpse of a trim white mustache and a silk hat. Looking at the outside of the building, you know that there is a big, high-ceiled room, at the front, dark in color and containing spacious leather chairs, which should (and often do) contain aristocratic gentlemen who have attained years of discretion and positions of importance. One feels cheated if, on entering, one fails to encounter a member carrying a malacca stick and wearing waxed mustaches, spats, and a gardenia. The Union Club of New York is such a club; so is the Pacific Union of San Francisco; so is the Chicago Club; and so, I fancy, from my glimpse of it, is the Union Club of Cleveland.