The Project Gutenberg EBook of Their Pilgrimage, by Charles Dudley Warner This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Their Pilgrimage Author: Charles Dudley Warner Release Date: August 22, 2006 [EBook #3102] Last Updated: February 24, 2018 Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THEIR PILGRIMAGE *** Produced by David Widger

CONTENTS

I. FORTRESS MONROE

II. CAPE MAY, ATLANTIC CITY

III. THE CATSKILLS

IV. NEWPORT

V. NARRAGANSETT PIER AND NEWPORT AGAIN;

MARTHA'S VINEYARD AND PLYMOUTH

VI. MANCHESTER-BY-THE-SEA, ISLES OF SHOALS

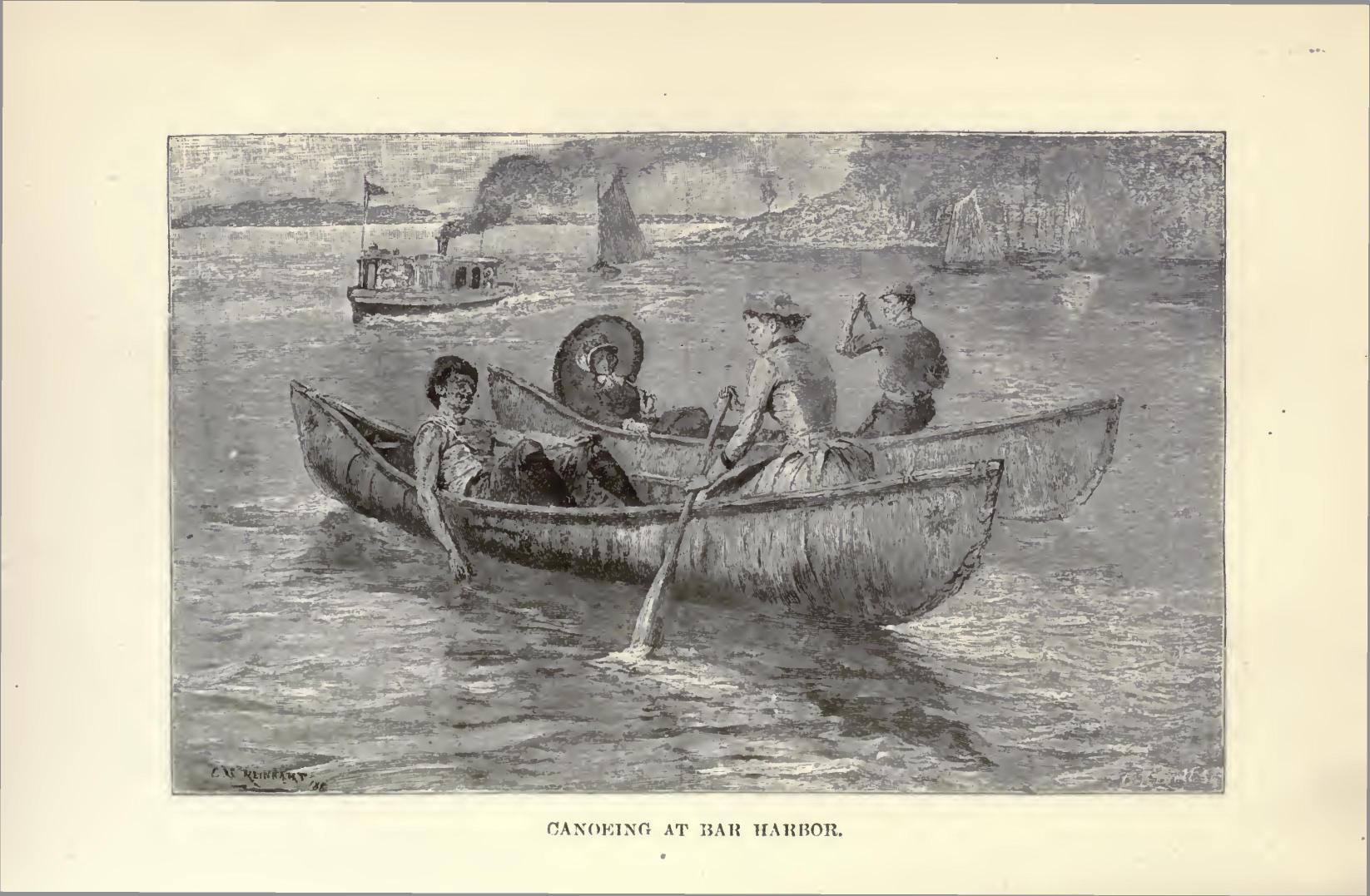

VII. BAR HARBOR

VIII. NATURAL BRIDGE, WHITE SULFUR

IX. OLD SWEET AND WHITE SULFUR

X. LONG BRANCH, OCEAN GROVE

XI. SARATOGA

XII. LAKE GEORGE, AND SARATOGA AGAIN

XIII. RICHFIELD SPRINGS, COOPERSTOWN

XIV. NIAGARA

XV. THE THOUSAND ISLES

XVI. WHITE MOUNTAINS, LENNOX

When Irene looked out of her stateroom window early in the morning of the twentieth of March, there was a softness and luminous quality in the horizon clouds that prophesied spring. The steamboat, which had left Baltimore and an arctic temperature the night before, was drawing near the wharf at Fortress Monroe, and the passengers, most of whom were seeking a mild climate, were crowding the guards, eagerly scanning the long facade of the Hygeia Hotel.

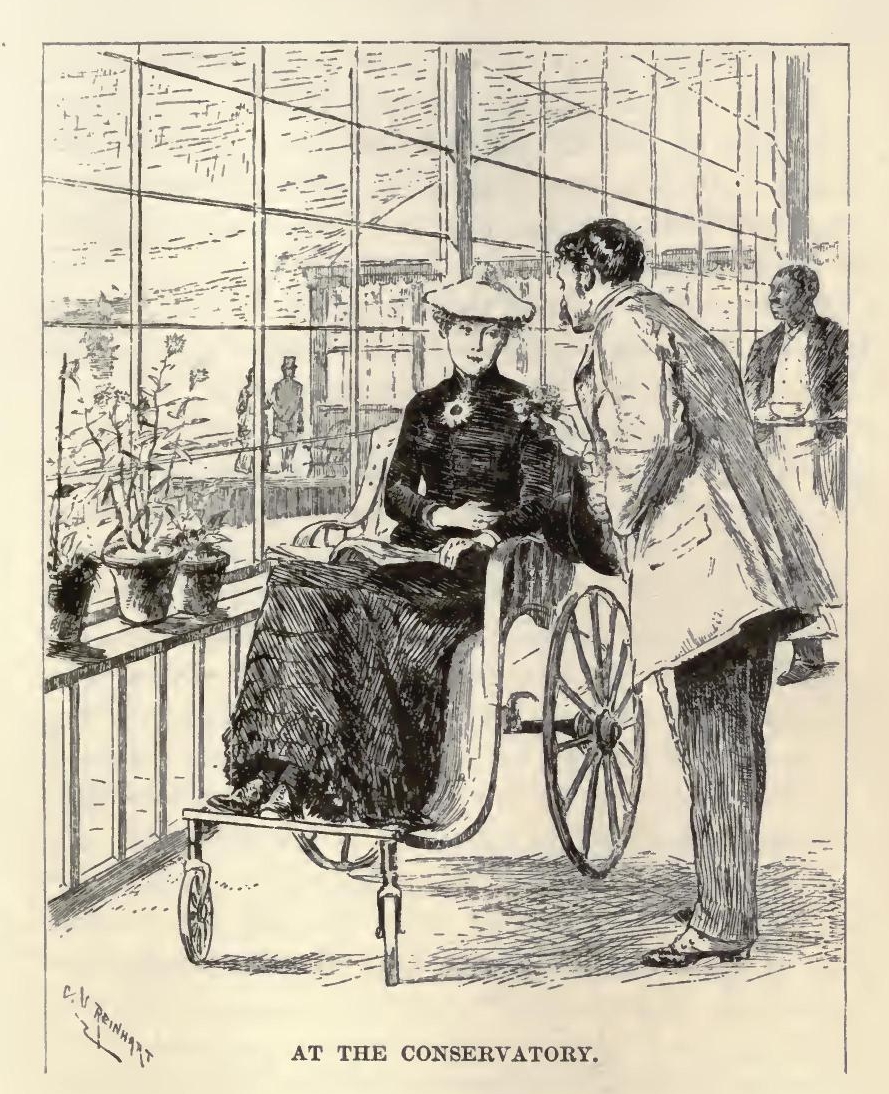

“It looks more like a conservatory than a hotel,” said Irene to her father, as she joined him.

“I expect that's about what it is. All those long corridors above and below enclosed in glass are to protect the hothouse plants of New York and Boston, who call it a Winter Resort, and I guess there's considerable winter in it.”

“But how charming it is—the soft sea air, the low capes yonder, the sails in the opening shining in the haze, and the peaceful old fort! I think it's just enchanting.”

“I suppose it is. Get a thousand people crowded into one hotel under glass, and let 'em buzz around—that seems to be the present notion of enjoyment. I guess your mother'll like it.”

And she did. Mrs. Benson, who appeared at the moment, a little flurried with her hasty toilet, a stout, matronly person, rather overdressed for traveling, exclaimed: “What a homelike looking place! I do hope the Stimpsons are here!”

“No doubt the Stimpsons are on hand,” said Mr. Benson. “Catch them not knowing what's the right thing to do in March! They know just as well as you do that the Reynoldses and the Van Peagrims are here.”

The crowd of passengers, alert to register and secure rooms, hurried up the windy wharf. The interior of the hotel kept the promise of the outside for comfort. Behind the glass-defended verandas, in the spacious office and general lounging-room, sea-coal fires glowed in the wide grates, tables were heaped with newspapers and the illustrated pamphlets in which railways and hotels set forth the advantages of leaving home; luxurious chairs invited the lazy and the tired, and the hotel-bureau, telegraph-office, railway-office, and post-office showed the new-comer that even in this resort he was still in the centre of activity and uneasiness. The Bensons, who had fortunately secured rooms a month in advance, sat quietly waiting while the crowd filed before the register, and took its fate from the courteous autocrat behind the counter. “No room,” was the nearly uniform answer, and the travelers had the satisfaction of writing their names and going their way in search of entertainment. “We've eight hundred people stowed away,” said the clerk, “and not a spot left for a hen to roost.”

At the end of the file Irene noticed a gentleman, clad in a perfectly-fitting rough traveling suit, with the inevitable crocodile hand-bag and tightly-rolled umbrella, who made no effort to enroll ahead of any one else, but having procured some letters from the post-office clerk, patiently waited till the rest were turned away, and then put down his name. He might as well have written it in his hat. The deliberation of the man, who appeared to be an old traveler, though probably not more than thirty years of age, attracted Irene's attention, and she could not help hearing the dialogue that followed.

“What can you do for me?”

“Nothing,” said the clerk.

“Can't you stow me away anywhere? It is Saturday, and very inconvenient for me to go any farther.”

“Cannot help that. We haven't an inch of room.”

“Well, where can I go?”

“You can go to Baltimore. You can go to Washington; or you can go to Richmond this afternoon. You can go anywhere.”

“Couldn't I,” said the stranger, with the same deliberation—“wouldn't you let me go to Charleston?”

“Why,” said the clerk, a little surprised, but disposed to accommodate—“why, yes, you can go to Charleston. If you take at once the boat you have just left, I guess you can catch the train at Norfolk.”

As the traveler turned and called a porter to reship his baggage, he was met by a lady, who greeted him with the cordiality of an old acquaintance and a volley of questions.

“Why, Mr. King, this is good luck. When did you come? have you a good room? What, no, not going?”

Mr. King explained that he had been a resident of Hampton Roads just fifteen minutes, and that, having had a pretty good view of the place, he was then making his way out of the door to Charleston, without any breakfast, because there was no room in the inn.

“Oh, that never'll do. That cannot be permitted,” said his engaging friend, with an air of determination. “Besides, I want you to go with us on an excursion today up the James and help me chaperon a lot of young ladies. No, you cannot go away.”

And before Mr. Stanhope King—for that was the name the traveler had inscribed on the register—knew exactly what had happened, by some mysterious power which women can exercise even in a hotel, when they choose, he found himself in possession of a room, and was gayly breakfasting with a merry party at a little round table in the dining-room.

“He appears to know everybody,” was Mrs. Benson's comment to Irene, as she observed his greeting of one and another as the guests tardily came down to breakfast. “Anyway, he's a genteel-looking party. I wonder if he belongs to Sotor, King and Co., of New York?”

“Oh, mother,” began Irene, with a quick glance at the people at the next table; and then, “if he is a genteel party, very likely he's a drummer. The drummers know everybody.”

And Irene confined her attention strictly to her breakfast, and never looked up, although Mrs. Benson kept prattling away about the young man's appearance, wondering if his eyes were dark blue or only dark gray, and why he didn't part his hair exactly in the middle and done with it, and a full, close beard was becoming, and he had a good, frank face anyway, and why didn't the Stimpsons come down; and, “Oh, there's the Van Peagrims,” and Mrs. Benson bowed sweetly and repeatedly to somebody across the room.

To an angel, or even to that approach to an angel in this world, a person who has satisfied his appetite, the spectacle of a crowd of people feeding together in a large room must be a little humiliating. The fact is that no animal appears at its best in this necessary occupation. But a hotel breakfast-room is not without interest. The very way in which people enter the room is a revelation of character. Mr. King, who was put in good humor by falling on his feet, as it were, in such agreeable company, amused himself by studying the guests as they entered. There was the portly, florid man, who “swelled” in, patronizing the entire room, followed by a meek little wife and three timid children. There was the broad, dowager woman, preceded by a meek, shrinking little man, whose whole appearance was an apology. There was a modest young couple who looked exceedingly self-conscious and happy, and another couple, not quite so young, who were not conscious of anybody, the gentleman giving a curt order to the waiter, and falling at once to reading a newspaper, while his wife took a listless attitude, which seemed to have become second nature. There were two very tall, very graceful, very high-bred girls in semi-mourning, accompanied by a nice lad in tight clothes, a model of propriety and slender physical resources, who perfectly reflected the gracious elevation of his sisters. There was a preponderance of women, as is apt to be the case in such resorts. A fact explicable not on the theory that women are more delicate than men, but that American men are too busy to take this sort of relaxation, and that the care of an establishment, with the demands of society and the worry of servants, so draw upon the nervous energy of women that they are glad to escape occasionally to the irresponsibility of hotel life. Mr. King noticed that many of the women had the unmistakable air of familiarity with this sort of life, both in the dining-room and at the office, and were not nearly so timid as some of the men. And this was very observable in the case of the girls, who were chaperoning their mothers—shrinking women who seemed a little confused by the bustle, and a little awed by the machinery of the great caravansary.

At length Mr. King's eye fell upon the Benson group. Usually it is unfortunate that a young lady should be observed for the first time at table. The act of eating is apt to be disenchanting. It needs considerable infatuation and perhaps true love on the part of a young man to make him see anything agreeable in this performance. However attractive a girl may be, the man may be sure that he is not in love if his admiration cannot stand this test. It is saying a great deal for Irene that she did stand this test even under the observation of a stranger, and that she handled her fork, not to put too fine a point upon it, in a manner to make the fastidious Mr. King desirous to see more of her. I am aware that this is a very unromantic view to take of one of the sweetest subjects in life, and I am free to confess that I should prefer that Mr. King should first have seen Irene leaning on the balustrade of the gallery, with a rose in her hand, gazing out over the sea with “that far-away look in her eyes.” It would have made it much easier for all of us. But it is better to tell the truth, and let the girl appear in the heroic attitude of being superior to her circumstances.

Presently Mr. King said to his friend, Mrs. Cortlandt, “Who is that clever-looking, graceful girl over there?”

“That,” said Mrs. Cortlandt, looking intently in the direction indicated—“why, so it is; that's just the thing,” and without another word she darted across the room, and Mr. King saw her in animated conversation with the young lady. Returning with satisfaction expressed in her face, she continued, “Yes, she'll join our party—without her mother. How lucky you saw her!”

“Well! Is it the Princess of Paphlagonia?”

“Oh, I forgot you were not in Washington last winter. That's Miss Benson; just charming; you'll see. Family came from Ohio somewhere. You'll see what they are—but Irene! Yes, you needn't ask; they've got money, made it honestly. Began at the bottom—as if they were in training for the presidency, you know—the mother hasn't got used to it as much as the father. You know how it is. But Irene has had every advantage—the best schools, masters, foreign travel, everything. Poor girl! I'm sorry for her. Sometimes I wish there wasn't any such thing as education in this country, except for the educated. She never shows it; but of course she must see what her relatives are.”

The Hotel Hygeia has this advantage, which is appreciated, at least by the young ladies. The United States fort is close at hand, with its quota of young officers, who have the leisure in times of peace to prepare for war, domestic or foreign; and there is a naval station across the bay, with vessels that need fashionable inspection. Considering the acknowledged scarcity of young men at watering-places, it is the duty of a paternal government to place its military and naval stations close to the fashionable resorts, so that the young women who are studying the german [(dance) D.W.] and other branches of the life of the period can have agreeable assistants. It is the charm of Fortress Monroe that its heroes are kept from ennui by the company assembled there, and that they can be of service to society.

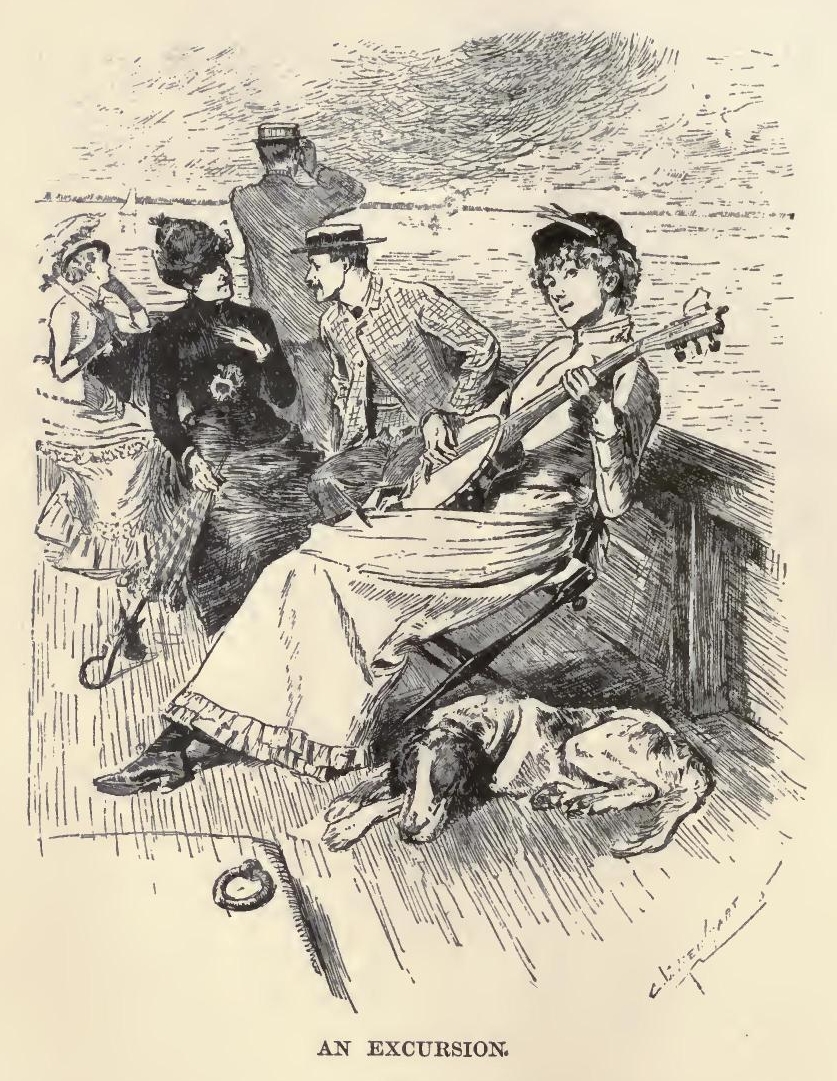

When Mrs. Cortlandt assembled her party on the steam-tug chartered by her for the excursion, the army was very well represented. With the exception of the chaperons and a bronzed veteran, who was inclined to direct the conversation to his Indian campaigns in the Black Hills, the company was young, and of the age and temper in which everything seems fair in love and war, and one that gave Mr. King, if he desired it, an opportunity of studying the girl of the period—the girl who impresses the foreigner with her extensive knowledge of life, her fearless freedom of manner, and about whom he is apt to make the mistake of supposing that this freedom has not perfectly well-defined limits. It was a delightful day, such as often comes, even in winter, within the Capes of Virginia; the sun was genial, the bay was smooth, with only a light breeze that kept the water sparkling brilliantly, and just enough tonic in the air to excite the spirits. The little tug, which was pretty well packed with the merry company, was swift, and danced along in an exhilarating manner. The bay, as everybody knows, is one of the most commodious in the world, and would be one of the most beautiful if it had hills to overlook it. There is, to be sure, a tranquil beauty in its wooded headlands and long capes, and it is no wonder that the early explorers were charmed with it, or that they lost their way in its inlets, rivers, and bays. The company at first made a pretense of trying to understand its geography, and asked a hundred questions about the batteries, and whence the Merrimac appeared, and where the Congress was sunk, and from what place the Monitor darted out upon its big antagonist. But everything was on a scale so vast that it was difficult to localize these petty incidents (big as they were in consequences), and the party soon abandoned history and geography for the enjoyment of the moment. Song began to take the place of conversation. A couple of banjos were produced, and both the facility and the repertoire of the young ladies who handled them astonished Irene. The songs were of love and summer seas, chansons in French, minor melodies in Spanish, plain declarations of affection in distinct English, flung abroad with classic abandon, and caught up by the chorus in lilting strains that partook of the bounding, exhilarating motion of the little steamer. Why, here is material, thought King, for a troupe of bacchantes, lighthearted leaders of a summer festival. What charming girls, quick of wit, dashing in repartee, who can pick the strings, troll a song, and dance a brando!

“It's like sailing over the Bay of Naples,” Irene was saying to Mr. King, who had found a seat beside her in the little cabin; “the guitar-strumming and the impassioned songs, only that always seems to me a manufactured gayety, an attempt to cheat the traveler into the belief that all life is a holiday. This is spontaneous.”

“Yes, and I suppose the ancient Roman gayety, of which the Neapolitan is an echo, was spontaneous once. I wonder if our society is getting to dance and frolic along like that of old at Baiae!”

“Oh, Mr. King, this is an excursion. I assure you the American girl is a serious and practical person most of the time. You've been away so long that your standards are wrong. She's not nearly so knowing as she seems to be.”

The boat was preparing to land at Newport News—a sand bank, with a railway terminus, a big elevator, and a hotel. The party streamed along in laughing and chatting groups, through the warehouse and over the tracks and the sandy hillocks to the hotel. On the way they captured a novel conveyance, a cart with an ox harnessed in the shafts, the property of an aged negro, whose white hair and variegated raiment proclaimed him an ancient Virginian, a survival of the war. The company chartered this establishment, and swarmed upon it till it looked like a Neapolitan 'calesso', and the procession might have been mistaken for a harvest-home—the harvest of beauty and fashion. The hotel was captured without a struggle on the part of the regular occupants, a dance extemporized in the dining-room, and before the magnitude of the invasion was realized by the garrison, the dancing feet and the laughing girls were away again, and the little boat was leaping along in the Elizabeth River towards the Portsmouth Navy-yard.

It isn't a model war establishment this Portsmouth yard, but it is a pleasant resort, with its stately barracks and open square and occasional trees. In nothing does the American woman better show her patriotism than in her desire to inspect naval vessels and understand dry-docks under the guidance of naval officers. Besides some old war hulks at the station, there were a couple of training-ships getting ready for a cruise, and it made one proud of his country to see the interest shown by our party in everything on board of them, patiently listening to the explanation of the breech-loading guns, diving down into the between-decks, crowded with the schoolboys, where it is impossible for a man to stand upright and difficult to avoid the stain of paint and tar, or swarming in the cabin, eager to know the mode of the officers' life at sea. So these are the little places where they sleep? and here is where they dine, and here is a library—a haphazard case of books in the saloon.

It was in running her eyes over these that a young lady discovered that the novels of Zola were among the nautical works needed in the navigation of a ship of war.

On the return—and the twenty miles seemed short enough—lunch was served, and was the occasion of a good deal of hilarity and innocent badinage. There were those who still sang, and insisted on sipping the heel-taps of the morning gayety; but was King mistaken in supposing that a little seriousness had stolen upon the party—a serious intention, namely, between one and another couple? The wind had risen, for one thing, and the little boat was so tossed about by the vigorous waves that the skipper declared it would be imprudent to attempt to land on the Rip-Raps. Was it the thought that the day was over, and that underneath all chaff and hilarity there was the question of settling in life to be met some time, which subdued a little the high spirits, and gave an air of protection and of tenderness to a couple here and there? Consciously, perhaps, this entered into the thought of nobody; but still the old story will go on, and perhaps all the more rapidly under a mask of raillery and merriment.

There was great bustling about, hunting up wraps and lost parasols and mislaid gloves, and a chorus of agreement on the delight of the day, upon going ashore, and Mrs. Cortlandt, who looked the youngest and most animated of the flock, was quite overwhelmed with thanks and congratulations upon the success of her excursion.

“Yes, it was perfect; you've given us all a great deal of pleasure, Mrs. Cortlandt,” Mr. King was saying, as he stood beside her, watching the exodus.

Perhaps Mrs. Cortlandt fancied his eyes were following a particular figure, for she responded, “And how did you like her?”

“Like her—Miss Benson? Why, I didn't see much of her. I thought she was very intelligent—seemed very much interested when Lieutenant Green was explaining to her what made the drydock dry—but they were all that. Did you say her eyes were gray? I couldn't make out if they were not rather blue after all—large, changeable sort of eyes, long lashes; eyes that look at you seriously and steadily, without the least bit of coquetry or worldliness; eyes expressing simplicity and interest in what you are saying—not in you, but in what you are saying. So few women know how to listen; most women appear to be thinking of themselves and the effect they are producing.”

Mrs. Cortlandt laughed. “Ah; I see. And a little 'sadness' in them, wasn't there? Those are the most dangerous eyes. The sort that follow you, that you see in the dark at night after the gas is turned off.”

“I haven't the faculty of seeing things in the dark, Mrs. Cortlandt. Oh, there's the mother!” And the shrill voice of Mrs. Benson was heard, “We was getting uneasy about you. Pa says a storm's coming, and that you'd be as sick as sick.”

The weather was changing. But that evening the spacious hotel, luxurious, perfectly warmed, and well lighted, crowded with an agreeable if not a brilliant company—for Mr. King noted the fact that none of the gentlemen dressed for dinner—seemed all the more pleasant for the contrast with the weather outside. Thus housed, it was pleasant to hear the waves dashing against the breakwater. Just by chance, in the ballroom, Mr. King found himself seated by Mrs. Benson and a group of elderly ladies, who had the perfunctory air of liking the mild gayety of the place. To one of them Mr. King was presented, Mrs. Stimpson—a stout woman with a broad red face and fishy eyes, wearing an elaborate head-dress with purple flowers, and attired as if she were expecting to take a prize. Mrs. Stimpson was loftily condescending, and asked Mr. King if this was his first visit. She'd been coming here years and years; never could get through the spring without a few weeks at the Hygeia. Mr. King saw a good many people at this hotel who seemed to regard it as a home.

“I hope your daughter, Mrs. Benson, was not tired out with the rather long voyage today.”

“Not a mite. I guess she enjoyed it. She don't seem to enjoy most things. She's got everything heart can wish at home. I don't know how it is. I was tellin' pa, Mr. Benson, today that girls ain't what they used to be in my time. Takes more to satisfy 'em. Now my daughter, if I say it as shouldn't, Mr. King, there ain't a better appearin,' nor smarter, nor more dutiful girl anywhere—well, I just couldn't live without her; and she's had the best schools in the East and Europe; done all Europe and Rome and Italy; and after all, somehow, she don't seem contented in Cyrusville—that's where we live in Ohio—one of the smartest places in the state; grown right up to be a city since we was married. She never says anything, but I can see. And we haven't spared anything on our house. And society—there's a great deal more society than I ever had.”

Mr. King might have been astonished at this outpouring if he had not observed that it is precisely in hotels and to entire strangers that some people are apt to talk with less reserve than to intimate friends.

“I've no doubt,” he said, “you have a lovely home in Cyrusville.”

“Well, I guess it's got all the improvements. Pa, Mr. Benson, said that he didn't know of anything that had been left out, and we had a man up from Cincinnati, who did all the furnishing before Irene came home.”

“Perhaps your daughter would have preferred to furnish it herself?”

“Mebbe so. She said it was splendid, but it looked like somebody else's house. She says the queerest things sometimes. I told Mr. Benson that I thought it would be a good thing to go away from home a little while and travel round. I've never been away much except in New York, where Mr. Benson has business a good deal. We've been in Washington this winter.”

“Are you going farther south?”

“Yes; we calculate to go down to the New Orleans Centennial. Pa wants to see the Exposition, and Irene wants to see what the South looks like, and so do I. I suppose it's perfectly safe now, so long after the war?”

“Oh, I should say so.”

“That's what Mr. Benson says. He says it's all nonsense the talk about what the South 'll do now the Democrats are in. He says the South wants to make money, and wants the country prosperous as much as anybody. Yes, we are going to take a regular tour all summer round to the different places where people go. Irene calls it a pilgrimage to the holy places of America. Pa thinks we'll get enough of it, and he's determined we shall have enough of it for once. I suppose we shall. I like to travel, but I haven't seen any place better than Cyrusville yet.”

As Irene did not make her appearance, Mr. King tore himself away from this interesting conversation and strolled about the parlors, made engagements to take early coffee at the fort, to go to church with Mrs. Cortlandt and her friends, and afterwards to drive over to Hampton and see the copper and other colored schools, talked a little politics over a late cigar, and then went to bed, rather curious to see if the eyes that Mrs. Cortlandt regarded as so dangerous would appear to him in the darkness.

When he awoke, his first faint impressions were that the Hygeia had drifted out to sea, and then that a dense fog had drifted in and enveloped it. But this illusion was speedily dispelled. The window-ledge was piled high with snow. Snow filled the air, whirled about by a gale that was banging the window-shutters and raging exactly like a Northern tempest.

It swirled the snow about in waves and dark masses interspersed with rifts of light, dark here and luminous there. The Rip-Raps were lost to view. Out at sea black clouds hung in the horizon, heavy reinforcements for the attacking storm. The ground was heaped with the still fast-falling snow—ten inches deep he heard it said when he descended. The Baltimore boat had not arrived, and could not get in. The waves at the wharf rolled in, black and heavy, with a sullen beat, and the sky shut down close to the water, except when a sudden stronger gust of wind cleared a luminous space for an instant. Stormbound: that is what the Hygeia was—a winter resort without any doubt.

The hotel was put to a test of its qualities. There was no getting abroad in such a storm. But the Hygeia appeared at its best in this emergency. The long glass corridors, where no one could venture in the arctic temperature, gave, nevertheless, an air of brightness and cheerfulness to the interior, where big fires blazed, and the company were exalted into good-fellowship and gayety—a decorous Sunday gayety—by the elemental war from which they were securely housed.

If the defenders of their country in the fortress mounted guard that morning, the guests at the Hygeia did not see them, but a good many of them mounted guard later at the hotel, and offered to the young ladies there that protection which the brave like to give the fair. Notwithstanding this, Mr. Stanhope King could not say the day was dull. After a morning presumably spent over works of a religious character, some of the young ladies, who had been the life of the excursion the day before, showed their versatility by devising serious amusements befitting the day, such as twenty questions on Scriptural subjects, palmistry, which on another day is an aid to mild flirtation, and an exhibition of mind-reading, not public—oh, dear, no—but with a favored group in a private parlor. In none of these groups, however, did Mr. King find Miss Benson, and when he encountered her after dinner in the reading-room, she confessed that she had declined an invitation to assist at the mind-reading, partly from a lack of interest, and partly from a reluctance to dabble in such things.

“Surely you are not uninterested in what is now called psychical research?” he asked.

“That depends,” said Irene. “If I were a physician, I should like to watch the operation of the minds of 'sensitives' as a pathological study. But the experiments I have seen are merely exciting and unsettling, without the least good result, with a haunting notion that you are being tricked or deluded. It is as much as I can do to try and know my own mind, without reading the minds of others.”

“But you cannot help the endeavor to read the mind of a person with whom you are talking.”

“Oh, that is different. That is really an encounter of wits, for you know that the best part of a conversation is the things not said. What they call mindreading is a vulgar business compared to this. Don't you think so, Mr. King?”

What Mr. King was actually thinking was that Irene's eyes were the most unfathomable blue he ever looked into, as they met his with perfect frankness, and he was wondering if she were reading his present state of mind; but what he said was, “I think your sort of mind-reading is a good deal more interesting than the other,” and he might have added, dangerous. For a man cannot attempt to find out what is in a woman's heart without a certain disturbance of his own. He added, “So you think our society is getting too sensitive and nervous, and inclined to make dangerous mental excursions?”

“I'm afraid I do not think much about such things,” Irene replied, looking out of the window into the storm. “I'm content with a very simple faith, even if it is called ignorance.”

Mr. King was thinking, as he watched the clear, spirited profile of the girl shown against the white tumult in the air, that he should like to belong to the party of ignorance himself, and he thought so long about it that the subject dropped, and the conversation fell into ordinary channels, and Mrs. Benson appeared. She thought they would move on as soon as the storm was over. Mr. King himself was going south in the morning, if travel were possible. When he said good-by, Mrs. Benson expressed the pleasure his acquaintance had given them, and hoped they should see him in Cyrusville. Mr. King looked to see if this invitation was seconded in Irene's eyes; but they made no sign, although she gave him her hand frankly, and wished him a good journey.

The next morning he crossed to Norfolk, was transported through the snow-covered streets on a sledge, and took his seat in the cars for the most monotonous ride in the country, that down the coast-line.

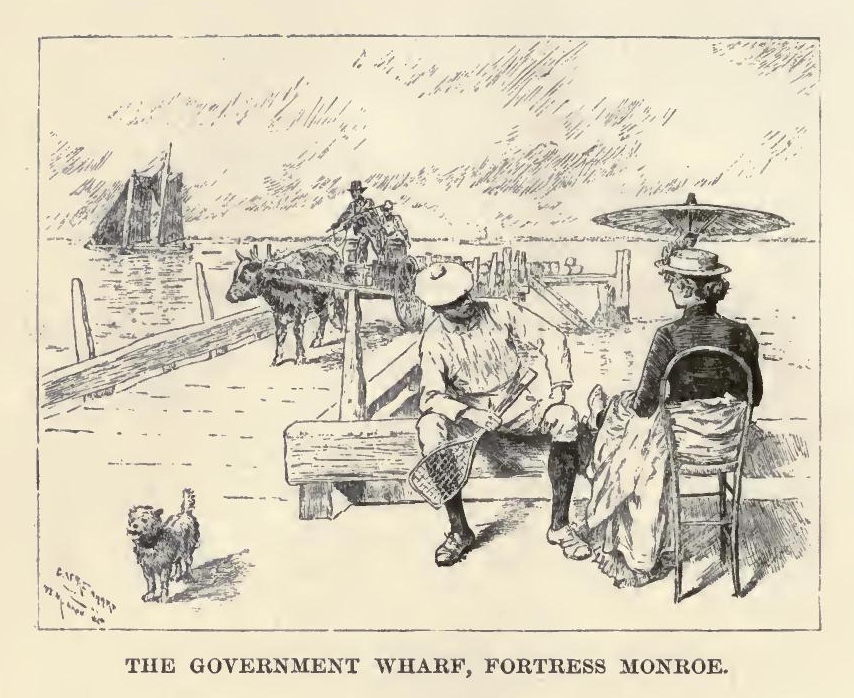

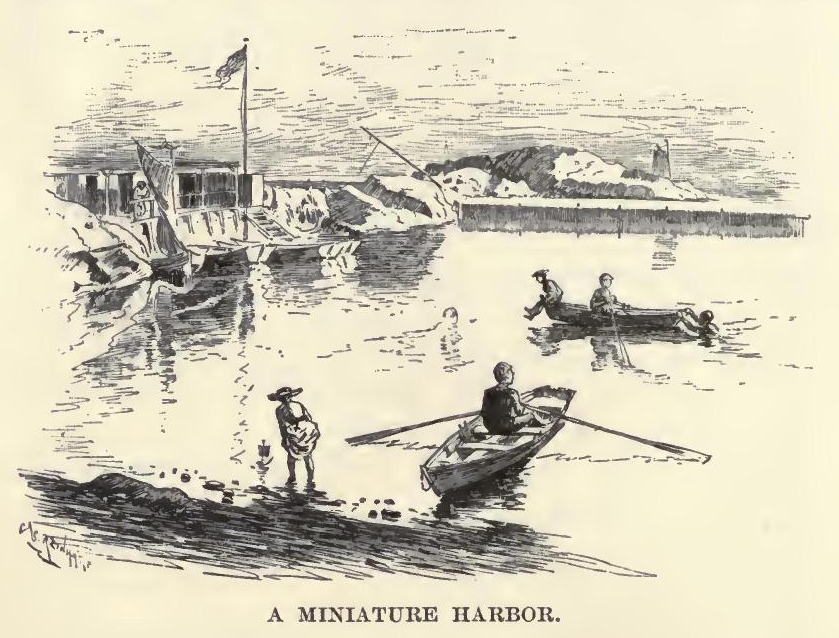

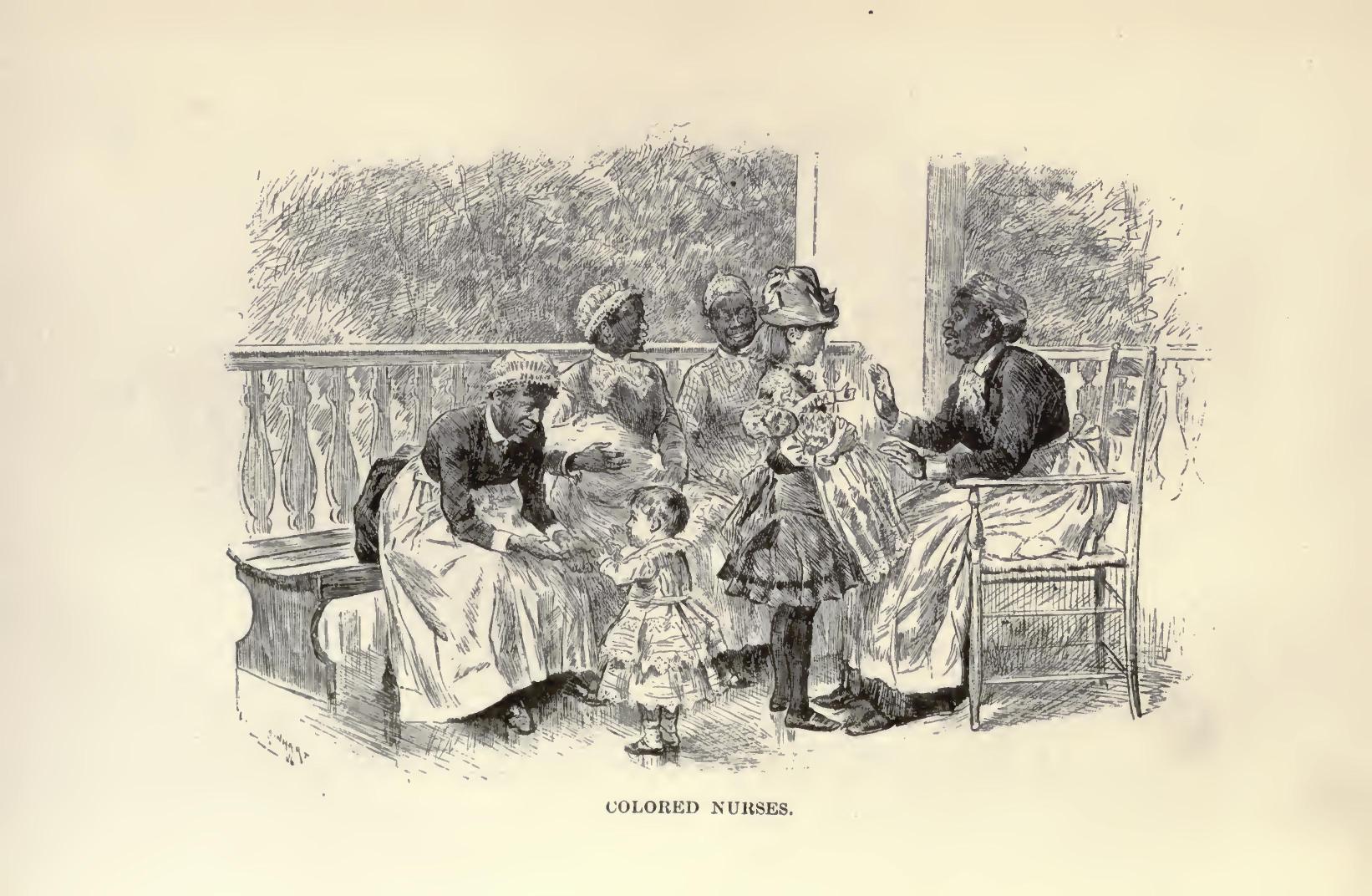

When next Stanhope King saw Fortress Monroe it was in the first days of June. The summer which he had left in the interior of the Hygeia was now out-of-doors. The winter birds had gone north; the summer birds had not yet come. It was the interregnum, for the Hygeia, like Venice, has two seasons, one for the inhabitants of colder climes, and the other for natives of the country. No spot, thought our traveler, could be more lovely. Perhaps certain memories gave it a charm, not well defined, but still gracious. If the house had been empty, which it was far from being, it would still have been peopled for him. Were they all such agreeable people whom he had seen there in March, or has one girl the power to throw a charm over a whole watering-place? At any rate, the place was full of delightful repose. There was movement enough upon the water to satisfy one's lazy longing for life, the waves lapped soothingly along the shore, and the broad bay, sparkling in the sun, was animated with boats, which all had a holiday air. Was it not enough to come down to breakfast and sit at the low, broad windows and watch the shifting panorama? All about the harbor slanted the white sails; at intervals a steamer was landing at the wharf or backing away from it; on the wharf itself there was always a little bustle, but no noise, some pretense of business, and much actual transaction in the way of idle attitudinizing, the colored man in castoff clothes, and the colored sister in sun-bonnet or turban, lending themselves readily to the picturesque; the scene changed every minute, the sail of a tiny boat was hoisted or lowered under the window, a dashing cutter with its uniformed crew was pulling off to the German man-of-war, a puffing little tug dragged along a line of barges in the distance, and on the horizon a fleet of coasters was working out between the capes to sea. In the open window came the fresh morning breeze, and only the softened sounds of the life outside. The ladies came down in cool muslin dresses, and added the needed grace to the picture as they sat breakfasting by the windows, their figures in silhouette against the blue water.

No wonder our traveler lingered there a little! Humanity called him, for one thing, to drive often with humanely disposed young ladies round the beautiful shore curve to visit the schools for various colors at Hampton. Then there was the evening promenading on the broad verandas and out upon the miniature pier, or at sunset by the water-batteries of the old fort—such a peaceful old fortress as it is. All the morning there were “inspections” to be attended, and nowhere could there be seen a more agreeable mingling of war and love than the spacious, tree-planted interior of the fort presented on such occasions. The shifting figures of the troops on parade; the martial and daring manoeuvres of the regimental band; the groups of ladies seated on benches under the trees, attended by gallants in uniform, momentarily off duty and full of information, and by gallants not in uniform and never off duty and desirous to learn; the ancient guns with French arms and English arms, reminiscences of Yorktown, on one of which a pretty girl was apt to be perched in the act of being photographed—all this was enough to inspire any man to be a countryman and a lover. It is beautiful to see how fearless the gentle sex is in the presence of actual war; the prettiest girls occupied the front and most exposed seats; and never flinched when the determined columns marched down on them with drums beating and colors flying, nor showed much relief when they suddenly wheeled and marched to another part of the parade in search of glory. And the officers' quarters in the casemates—what will not women endure to serve their country! These quarters are mere tunnels under a dozen feet of earth, with a door on the parade side and a casement window on the outside—a damp cellar, said to be cool in the height of summer. The only excuse for such quarters is that the women and children will be comparatively safe in case the fortress is bombarded.

The hotel and the fortress at this enchanting season, to say nothing of other attractions, with laughing eyes and slender figures, might well have detained Mr. Stanhope King, but he had determined upon a sort of roving summer among the resorts of fashion and pleasure. After a long sojourn abroad, it seemed becoming that he should know something of the floating life of his own country. His determination may have been strengthened by the confession of Mrs. Benson that her family were intending an extensive summer tour. It gives a zest to pleasure to have even an indefinite object, and though the prospect of meeting Irene again was not definite, it was nevertheless alluring. There was something about her, he could not tell what, different from the women he had met in France. Indeed, he went so far as to make a general formula as to the impression the American women made on him at Fortress Monroe—they all appeared to be innocent.

“Of course you will not go to Cape May till the season opens. You might as well go to a race-track the day there is no race.” It was Mrs. Cortlandt who was speaking, and the remonstrance was addressed to Mr. Stanhope King, and a young gentleman, Mr. Graham Forbes, who had just been presented to her as an artist, in the railway station at Philadelphia, that comfortable home of the tired and bewildered traveler. Mr. Forbes, with his fresh complexion, closely cropped hair, and London clothes, did not look at all like the traditional artist, although the sharp eyes of Mrs. Cortlandt detected a small sketch-book peeping out of his side pocket.

“On the contrary, that is why we go,” said Mr. King. “I've a fancy that I should like to open a season once myself.”

“Besides,” added Mr. Forbes, “we want to see nature unadorned. You know, Mrs. Cortlandt, how people sometimes spoil a place.”

“I'm not sure,” answered the lady, laughing, “that people have not spoiled you two and you need a rest. Where else do you go?”

“Well, I thought,” replied Mr. King, “from what I heard, that Atlantic City might appear best with nobody there.”

“Oh, there's always some one there. You know, it is a winter resort now. And, by the way—But there's my train, and the young ladies are beckoning to me.” (Mrs. Cortlandt was never seen anywhere without a party of young ladies.) “Yes, the Bensons passed through Washington the other day from the South, and spoke of going to Atlantic City to tone up a little before the season, and perhaps you know that Mrs. Benson took a great fancy to you, Mr. King. Good-by, au revoir,” and the lady was gone with her bevy of girls, struggling in the stream that poured towards one of the wicket-gates.

“Atlantic City? Why, Stanhope, you don't think of going there also?”

“I didn't think of it, but, hang it all, my dear fellow, duty is duty. There are some places you must see in order to be well informed. Atlantic City is an important place; a great many of its inhabitants spend their winters in Philadelphia.”

“And this Mrs. Benson?”

“No, I'm not going down there to see Mrs. Benson.”

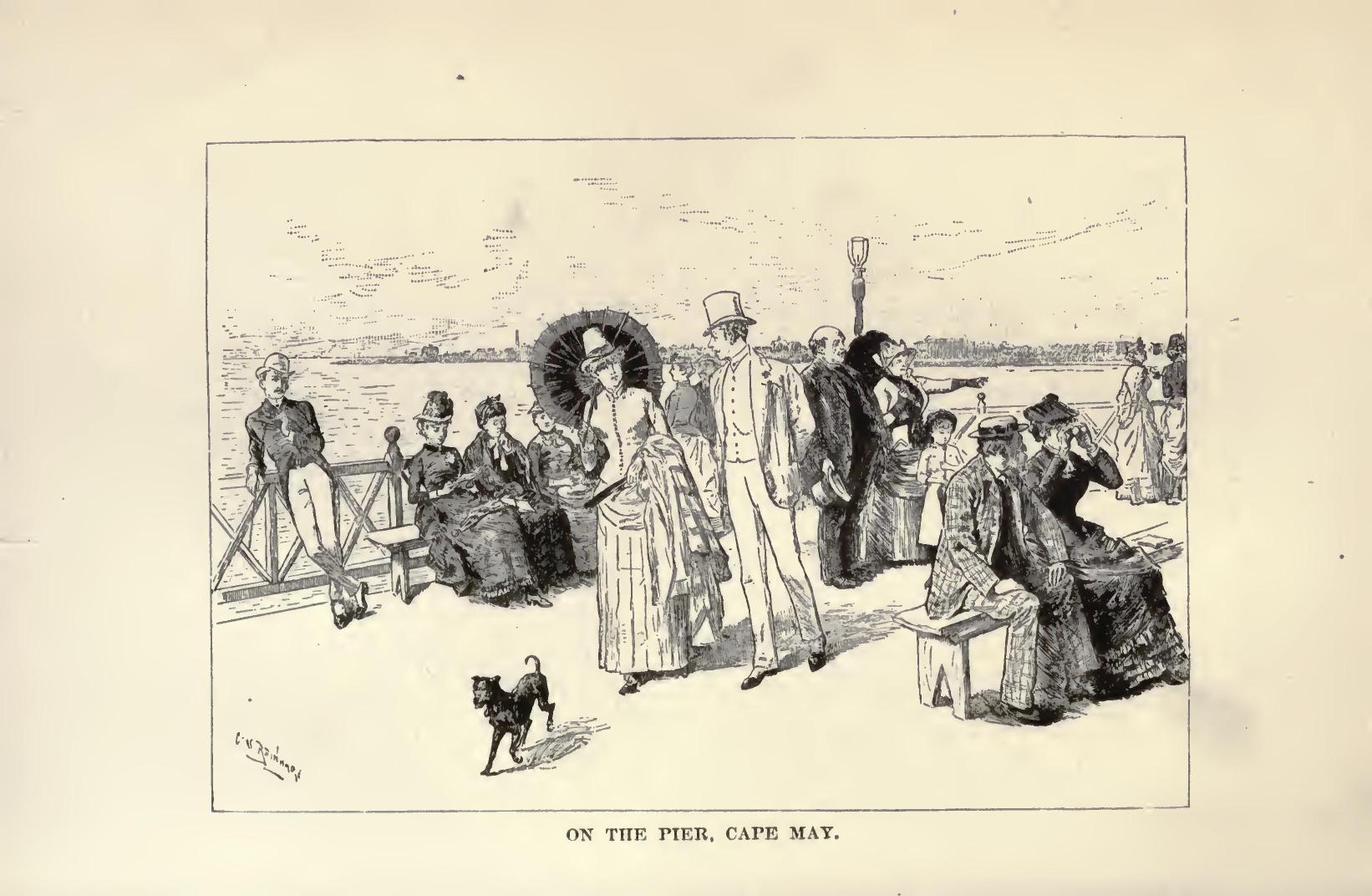

Expectancy was the word when our travelers stepped out of the car at Cape May station. Except for some people who seemed to have business there, they were the only passengers. It was the ninth of June. Everything was ready—the sea, the sky, the delicious air, the long line of gray-colored coast, the omnibuses, the array of hotel tooters. As they stood waiting in irresolution a grave man of middle age and a disinterested manner sauntered up to the travelers, and slipped into friendly relations with them. It was impossible not to incline to a person so obliging and well stocked with local information. Yes, there were several good hotels open. It didn't make much difference; there was one near at hand, not pretentious, but probably as comfortable as any. People liked the table; last summer used to come there from other hotels to get a meal. He was going that way, and would walk along with them. He did, and conversed most interestingly on the way. Our travelers felicitated themselves upon falling into such good hands, but when they reached the hotel designated it had such a gloomy and in fact boardinghouse air that they hesitated, and thought they would like to walk on a little farther and see the town before settling. And their friend appeared to feel rather grieved about it, not for himself, but for them. He had moreover, the expression of a fisherman who has lost a fish after he supposed it was securely hooked. But our young friends had been angled for in a good many waters, and they told the landlord, for it was the landlord, that while they had no doubt his was the best hotel in the place, they would like to look at some not so good. The one that attracted them, though they could not see in what the attraction lay, was a tall building gay with fresh paint in many colors, some pretty window balconies, and a portico supported by high striped columns that rose to the fourth story. They were fond of color, and were taken by six little geraniums planted in a circle amid the sand in front of the house, which were waiting for the season to open before they began to grow. With hesitation they stepped upon the newly varnished piazza and the newly varnished office floor, for every step left a footprint. The chairs, disposed in a long line on the piazza, waiting for guests, were also varnished, as the artist discovered when he sat in one of them and was held fast. It was all fresh and delightful. The landlord and the clerks had smiles as wide as the open doors; the waiters exhibited in their eagerness a good imitation of unselfish service.

It was very pleasant to be alone in the house, and to be the first-fruits of such great expectations. The first man of the season is in such a different position from the last. He is like the King of Bavaria alone in his royal theatre. The ushers give him the best seat in the house, he hears the tuning of the instruments, the curtain is about to rise, and all for him. It is a very cheerful desolation, for it has a future, and everything quivers with the expectation of life and gayety. Whereas the last man is like one who stumbles out among the empty benches when the curtain has fallen and the play is done. Nothing is so melancholy as the shabbiness of a watering-place at the end of the season, where is left only the echo of past gayety, the last guests are scurrying away like leaves before the cold, rising wind, the varnish has worn off, shutters are put up, booths are dismantled, the shows are packing up their tawdry ornaments, and the autumn leaves collect in the corners of the gaunt buildings.

Could this be the Cape May about which hung so many traditions of summer romance? Where were those crowds of Southerners, with slaves and chariots, and the haughtiness of a caste civilization, and the belles from Baltimore and Philadelphia and Charleston and Richmond, whose smiles turned the heads of the last generation? Had that gay society danced itself off into the sea, and left not even a phantom of itself behind? As he sat upon the veranda, King could not rid himself of the impression that this must be a mocking dream, this appearance of emptiness and solitude. Why, yes, he was certainly in a delusion, at least in a reverie. The place was alive. An omnibus drove to the door (though no sound of wheels was heard); the waiters rushed out, a fat man descended, a little girl was lifted down, a pretty woman jumped from the steps with that little extra bound on the ground which all women confessedly under forty always give when they alight from a vehicle, a large woman lowered herself cautiously out, with an anxious look, and a file of men stooped and emerged, poking their umbrellas and canes in each other's backs. Mr. King plainly saw the whole party hurry into the office and register their names, and saw the clerk repeatedly touch a bell and throw back his head and extend his hand to a servant. Curious to see who the arrivals were, he went to the register. No names were written there. But there were other carriages at the door, there was a pile of trunks on the veranda, which he nearly stumbled over, although his foot struck nothing, and the chairs were full, and people were strolling up and down the piazza. He noticed particularly one couple promenading—a slender brunette, with a brilliant complexion; large dark eyes that made constant play—could it be the belle of Macon?—and a gentleman of thirty-five, in black frock-coat, unbuttoned, with a wide-brimmed soft hat-clothes not quite the latest style—who had a good deal of manner, and walked apart from the young lady, bending towards her with an air of devotion. Mr. King stood one side and watched the endless procession up and down, up and down, the strollers, the mincers, the languid, the nervous steppers; noted the eye-shots, the flashing or the languishing look that kills, and never can be called to account for the mischief it does; but not a sound did he hear of the repartee and the laughter. The place certainly was thronged. The avenue in front was crowded with vehicles of all sorts; there were groups strolling on the broad beach-children with their tiny pails and shovels digging pits close to the advancing tide, nursery-maids in fast colors, boys in knickerbockers racing on the beach, people lying on the sand, resolute walkers, whose figures loomed tall in the evening light, doing their constitutional. People were passing to and fro on the long iron pier that spider-legged itself out into the sea; the two rooms midway were filled with sitters taking the evening breeze; and the large ball and music room at the end, with its spacious outside promenade-yes, there were dancers there, and the band was playing. Mr. King could see the fiddlers draw their bows, and the corneters lift up their horns and get red in the face, and the lean man slide his trombone, and the drummer flourish his sticks, but not a note of music reached him. It might have been a performance of ghosts for all the effect at this distance.

Mr. King remarked upon this dumb-show to a gentleman in a blue coat and white vest and gray hat, leaning against a column near him. The gentleman made no response. It was most singular. Mr. King stepped back to be out of the way of some children racing down the piazza, and, half stumbling, sat down in the lap of a dowager—no, not quite; the chair was empty, and he sat down in the fresh varnish, to which his clothes stuck fast. Was this a delusion? No. The tables were filled in the dining-room, the waiters were scurrying about, there were ladies on the balconies looking dreamily down upon the animated scene below; all the movements of gayety and hilarity in the height of a season. Mr. King approached a group who were standing waiting for a carriage, but they did not see him, and did not respond to his trumped-up question about the next train. Were these, then, shadows, or was he a spirit himself? Were these empty omnibuses and carriages that discharged ghostly passengers? And all this promenading and flirting and languishing and love-making, would it come to nothing-nothing more than usual? There was a charm about it all—the movement, the color, the gray sand, and the rosy blush on the sea—a lovely place, an enchanted place. Were these throngs the guests that were to come, or those that had been herein other seasons? Why could not the former “materialize” as well as the latter? Is it not as easy to make nothing out of what never yet existed as out of what has ceased to exist? The landlord, by faith, sees all this array which is prefigured so strangely to Mr. King; and his comely young wife sees it and is ready for it; and the fat son at the supper table—a living example of the good eating to be had here—is serene, and has the air of being polite and knowing to a houseful. This scrap of a child, with the aplomb of a man of fifty, wise beyond his fatness, imparts information to the travelers about the wine, speaks to the waiter with quiet authority, and makes these mature men feel like boys before the gravity of our perfect flower of American youth who has known no childhood. This boy at least is no phantom; the landlord is real, and the waiters, and the food they bring.

“I suppose,” said Mr. King to his friend, “that we are opening the season. Did you see anything outdoors?”

“Yes; a horseshoe-crab about a mile below here on the smooth sand, with a long dotted trail behind him, a couple of girls in a pony-cart who nearly drove over me, and a tall young lady with a red parasol, accompanied by a big black-and-white dog, walking rapidly, close to the edge of the sea, towards the sunset. It's just lovely, the silvery sweep of coast in this light.”

“It seems a refined sort of place in its outlines, and quietly respectable. They tell me here that they don't want the excursion crowds that overrun Atlantic City, but an Atlantic City man, whom I met at the pier, said that Cape May used to be the boss, but that Atlantic City had got the bulge on it now—had thousands to the hundreds here. To get the bulge seems a desirable thing in America, and I think we'd better see what a place is like that is popular, whether fashion recognizes it or not.”

The place lost nothing in the morning light, and it was a sparkling morning with a fresh breeze. Nature, with its love of simple, sweeping lines, and its feeling for atmospheric effect, has done everything for the place, and bad taste has not quite spoiled it. There is a sloping, shallow beach, very broad, of fine, hard sand, excellent for driving or for walking, extending unbroken three miles down to Cape May Point, which has hotels and cottages of its own, and lifesaving and signal stations. Off to the west from this point is the long sand line to Cape Henlopen, fourteen miles away, and the Delaware shore. At Cape May Point there is a little village of painted wood houses, mostly cottages to let, and a permanent population of a few hundred inhabitants. From the pier one sees a mile and a half of hotels and cottages, fronting south, all flaming, tasteless, carpenter's architecture, gay with paint. The sea expanse is magnificent, and the sweep of beach is fortunately unencumbered, and vulgarized by no bath-houses or show-shanties. The bath-houses are in front of the hotels and in their enclosures; then come the broad drive, and the sand beach, and the sea. The line is broken below by the lighthouse and a point of land, whereon stands the elephant. This elephant is not indigenous, and he stands alone in the sand, a wooden sham without an explanation. Why the hotel-keeper's mind along the coast regards this grotesque structure as a summer attraction it is difficult to see. But when one resort had him, he became a necessity everywhere. The travelers walked down to this monster, climbed the stairs in one of his legs, explored the rooms, looked out from the saddle, and pondered on the problem. This beast was unfinished within and unpainted without, and already falling into decay. An elephant on the desert, fronting the Atlantic Ocean, had, after all, a picturesque aspect, and all the more so because he was a deserted ruin.

The elephant was, however, no emptier than the cottages about which our friends strolled. But the cottages were all ready, the rows of new chairs stood on the fresh piazzas, the windows were invitingly open, the pathetic little patches of flowers in front tried hard to look festive in the dry sands, and the stout landladies in their rocking-chairs calmly knitted and endeavored to appear as if they expected nobody, but had almost a houseful.

Yes, the place was undeniably attractive. The sea had the blue of Nice; why must we always go to the Mediterranean for an aqua marina, for poetic lines, for delicate shades? What charming gradations had this picture-gray sand, blue waves, a line of white sails against the pale blue sky! By the pier railing is a bevy of little girls grouped about an ancient colored man, the very ideal old Uncle Ned, in ragged, baggy, and disreputable clothes, lazy good-nature oozing out of every pore of him, kneeling by a telescope pointed to a bunch of white sails on the horizon; a dainty little maiden, in a stiff white skirt and golden hair, leans against him and tiptoes up to the object-glass, shutting first one eye and then the other, and making nothing out of it all. “Why, ov co'se you can't see nuffln, honey,” said Uncle Ned, taking a peep, “wid the 'scope p'inted up in the sky.”

In order to pass from Cape May to Atlantic City one takes a long circuit by rail through the Jersey sands. Jersey is a very prolific State, but the railway traveler by this route is excellently prepared for Atlantic City, for he sees little but sand, stunted pines, scrub oaks, small frame houses, sometimes trying to hide in the clumps of scrub oaks, and the villages are just collections of the same small frame houses hopelessly decorated with scroll-work and obtrusively painted, standing in lines on sandy streets, adorned with lean shade-trees. The handsome Jersey people were not traveling that day—the two friends had a theory about the relation of a sandy soil to female beauty—and when the artist got out his pencil to catch the types of the country, he was well rewarded. There were the fat old women in holiday market costumes, strong-featured, positive, who shook their heads at each other and nodded violently and incessantly, and all talked at once; the old men in rusty suits, thin, with a deprecatory manner, as if they had heard that clatter for fifty years, and perky, sharp-faced girls in vegetable hats, all long-nosed and thin-lipped. And though the day was cool, mosquitoes had the bad taste to invade the train. At the junction, a small collection of wooden shanties, where the travelers waited an hour, they heard much of the glories of Atlantic City from the postmistress, who was waiting for an excursion some time to go there (the passion for excursions seems to be a growing one), and they made the acquaintance of a cow tied in the room next the ticket-office, probably also waiting for a passage to the city by the sea.

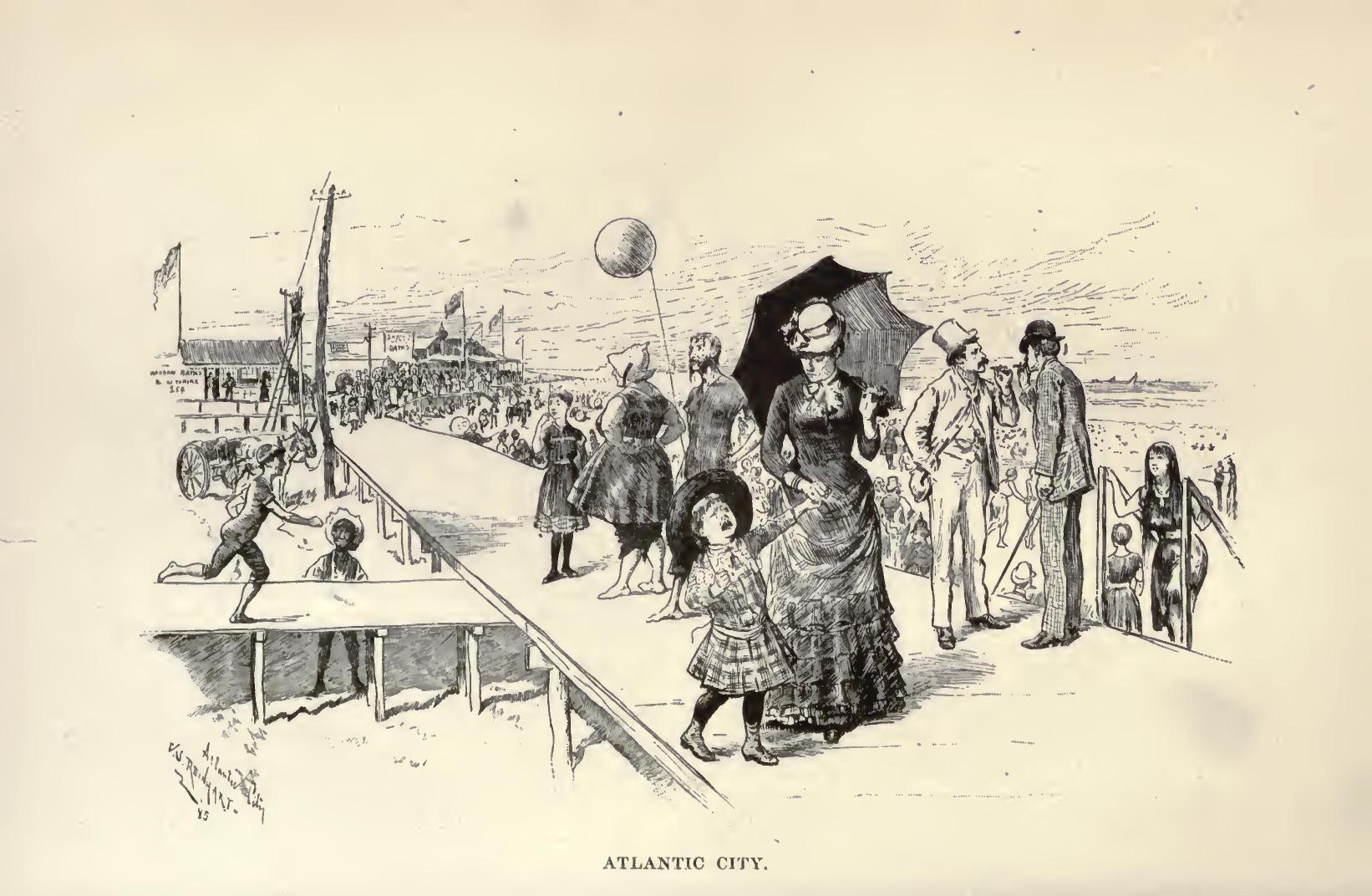

And a city it is. If many houses, endless avenues, sand, paint, make a city, the artist confessed that this was one. Everything is on a large scale. It covers a large territory, the streets run at right angles, the avenues to the ocean take the names of the states. If the town had been made to order and sawed out by one man, it could not be more beautifully regular and more satisfactorily monotonous. There is nothing about it to give the most commonplace mind in the world a throb of disturbance. The hotels, the cheap shops, the cottages, are all of wood, and, with three or four exceptions in the thousands, they are all practically alike, all ornamented with scroll-work, as if cut out by the jig-saw, all vividly painted, all appealing to a primitive taste just awakening to the appreciation of the gaudy chromo and the illuminated and consoling household motto. Most of the hotels are in the town, at considerable distance from the ocean, and the majestic old sea, which can be monotonous but never vulgar, is barricaded from the town by five or six miles of stark-naked plank walk, rows on rows of bath closets, leagues of flimsy carpentry-work, in the way of cheap-John shops, tin-type booths, peep-shows, go-rounds, shooting-galleries, pop-beer and cigar shops, restaurants, barber shops, photograph galleries, summer theatres. Sometimes the plank walk runs for a mile or two, on its piles, between rows of these shops and booths, and again it drops off down by the waves. Here and there is a gayly-painted wooden canopy by the shore, with chairs where idlers can sit and watch the frolicking in the water, or a space railed off, where the select of the hotels lie or lounge in the sand under red umbrellas. The calculating mind wonders how many million feet of lumber there are in this unpicturesque barricade, and what gigantic forests have fallen to make this timber front to the sea. But there is one thing man cannot do. He has made this show to suit himself, he has pushed out several iron piers into the sea, and erected, of course, a skating rink on the end of one of them. But the sea itself, untamed, restless, shining, dancing, raging, rolls in from the southward, tossing the white sails on its vast expanse, green, blue, leaden, white-capped, many-colored, never two minutes the same, sounding with its eternal voice I knew not what rebuke to man.

When Mr. King wrote his and his friend's name in the book at the Mansion House, he had the curiosity to turn over the leaves, and it was not with much surprise that he read there the names of A. J. Benson, wife, and daughter, Cyrusville, Ohio.

“Oh, I see!” said the artist; “you came down here to see Mr. Benson!”

That gentleman was presently discovered tilted back in a chair on the piazza, gazing vacantly into the vacant street with that air of endurance that fathers of families put on at such resorts. But he brightened up when Mr. King made himself known.

“I'm right glad to see you, sir. And my wife and daughter will be. I was saying to my wife yesterday that I couldn't stand this sort of thing much longer.”

“You don't find it lively?”

“Well, the livelier it is the less I shall like it, I reckon. The town is well enough. It's one of the smartest places on the coast. I should like to have owned the ground and sold out and retired. This sand is all gold. They say they sell the lots by the bushel and count every sand. You can see what it is, boards and paint and sand. Fine houses, too; miles of them.”

“And what do you do?”

“Oh, they say there's plenty to do. You can ride around in the sand; you can wade in it if you want to, and go down to the beach and walk up and down the plank walk—walk up and down—walk up and down. They like it. You can't bathe yet without getting pneumonia. They have gone there now. Irene goes because she says she can't stand the gayety of the parlor.”

From the parlor came the sound of music. A young girl who had the air of not being afraid of a public parlor was drumming out waltzes on the piano, more for the entertainment of herself than of the half-dozen ladies who yawned over their worsted-work. As she brought her piece to an end with a bang, a pretty, sentimental miss with a novel in her hand, who may not have seen Mr. King looking in at the door, ran over to the player and gave her a hug. “That's beautiful! that's perfectly lovely, Mamie!”—“This,” said the player, taking up another sheet, “has not been played much in New York.” Probably not, in that style, thought Mr. King, as the girl clattered through it.

There was no lack of people on the promenade, tramping the boards, or hanging about the booths where the carpenters and painters were at work, and the shop men and women were unpacking the corals and the sea-shells, and the cheap jewelry, and the Swiss wood-carving, the toys, the tinsel brooches, and agate ornaments, and arranging the soda fountains, and putting up the shelves for the permanent pie. The sort of preparation going on indicated the kind of crowd expected. If everything had a cheap and vulgar look, our wandering critics remembered that it is never fair to look behind the scenes of a show, and that things would wear a braver appearance by and by. And if the women on the promenade were homely and ill-dressed, even the bonnes in unpicturesque costumes, and all the men were slouchy and stolid, how could any one tell what an effect of gayety and enjoyment there might be when there were thousands of such people, and the sea was full of bathers, and the flags were flying, and the bands were tooting, and all the theatres were opened, and acrobats and spangled women and painted red-men offered those attractions which, like government, are for the good of the greatest number? What will you have? Shall vulgarity be left just vulgar, and have no apotheosis and glorification? This is very fine of its kind, and a resort for the million. The million come here to enjoy themselves. Would you have an art-gallery here, and high-priced New York and Paris shops lining the way?

“Look at the town,” exclaimed the artist, “and see what money can do, and satisfy the average taste without the least aid from art. It's just wonderful. I've tramped round the place, and, taking out a cottage or two, there isn't a picturesque or pleasing view anywhere. I tell you people know what they want, and enjoy it when they get it.”

“You needn't get excited about it,” said Mr. King. “Nobody said it wasn't commonplace, and glaringly vulgar if you like, and if you like to consider it representative of a certain stage in national culture, I hope it is not necessary to remind you that the United States can beat any other people in any direction they choose to expand themselves. You'll own it when you've seen watering-places enough.”

After this defense of the place, Mr. King owned it might be difficult for Mr. Forbes to find anything picturesque to sketch. What figures, to be sure! As if people were obliged to be shapely or picturesque for the sake of a wandering artist! “I could do a tree,” growled Mr. Forbes, “or a pile of boards; but these shanties!”

When they were well away from the booths and bath-houses, Mr. King saw in the distance two ladies. There was no mistaking one of them—the easy carriage, the grace of movement. No such figure had been afield all day. The artist was quick to see that. Presently they came up with them, and found them seated on a bench, looking off upon Brigantine Island, a low sand dune with some houses and a few trees against the sky, the most pleasing object in view.

Mrs. Benson did not conceal the pleasure she felt in seeing Mr. King again, and was delighted to know his friend; and, to say the truth, Miss Irene gave him a very cordial greeting.

“I'm 'most tired to death,” said Mrs. Benson, when they were all seated. “But this air does me good. Don't you like Atlantic City?”

“I like it better than I did at first.” If the remark was intended for Irene, she paid no attention to it, being absorbed in explaining to Mr. Forbes why she preferred the deserted end of the promenade.

“It's a place that grows on you. I guess it's grown the wrong way on Irene and father; but I like the air—after the South. They say we ought to see it in August, when all Philadelphia is here.”

“I should think it might be very lively.”

“Yes; but the promiscuous bathing. I don't think I should like that. We are not brought up to that sort of thing in Ohio.”

“No? Ohio is more like France, I suppose?”

“Like France!” exclaimed the old lady, looking at him in amazement—“like France! Why, France is the wickedest place in the world.”

“No doubt it is, Mrs. Benson. But at the sea resorts the sexes bathe separately.”

“Well, now! I suppose they have to there.”

“Yes; the older nations grow, the more self-conscious they become.”

“I don't believe, for all you say, Mr. King, the French have any more conscience than we have.”

“Nor do I, Mrs. Benson. I was only trying to say that they pay more attention to appearances.”

“Well, I was brought up to think it's one thing to appear, and another thing to be,” said Mrs. Benson, as dismissing the subject. “So your friend's an artist? Does he paint? Does he take portraits? There was an artist at Cyrusville last winter who painted portraits, but Irene wouldn't let him do hers. I'm glad we've met Mr. Forbes. I've always wanted to have—”

“Oh, mother,” exclaimed Irene, who always appeared to keep one ear for her mother's conversation, “I was just saying to Mr. Forbes that he ought to see the art exhibitions down at the other end of the promenade, and the pictures of the people who come here in August. Are you rested?”

The party moved along, and Mr. King, by a movement that seemed to him more natural than it did to Mr. Forbes, walked with Irene, and the two fell to talking about the last spring's trip in the South.

“Yes, we enjoyed the exhibition, but I am not sure but I should have enjoyed New Orleans more without the exhibition. That took so much time. There is nothing so wearisome as an exhibition. But New Orleans was charming. I don't know why, for it's the flattest, dirtiest, dampest city in the world; but it is charming. Perhaps it's the people, or the Frenchiness of it, or the tumble-down, picturesque old creole quarter, or the roses; I didn't suppose there were in the world so many roses; the town was just wreathed and smothered with them. And you did not see it?”

“No; I have been to exhibitions, and I thought I should prefer to take New Orleans by itself some other time. You found the people hospitable?”

“Well, they were not simply hospitable; they were that, to be sure, for father had letters to some of the leading men; but it was the general air of friendliness and good-nature everywhere, of agreeableness—it went along with the roses and the easy-going life. You didn't feel all the time on a strain. I don't suppose they are any better than our people, and I've no doubt I should miss a good deal there after a while—a certain tonic and purpose in life. But, do you know, it is pleasant sometimes to be with people who haven't so many corners as our people have. But you went south from Fortress Monroe?”

“Yes; I went to Florida.”

“Oh, that must be a delightful country!”

“Yes, it's a very delightful land, or will be when it is finished. It needs advertising now. It needs somebody to call attention to it. The modest Northerners who have got hold of it, and staked it all out into city lots, seem to want to keep it all to themselves.”

“How do you mean 'finished'?”

“Why, the State is big enough, and a considerable portion of it has a good foundation. What it wants is building up. There's plenty of water and sand, and palmetto roots and palmetto trees, and swamps, and a perfectly wonderful vegetation of vines and plants and flowers. What it needs is land—at least what the Yankees call land. But it is coming on. A good deal of the State below Jacksonville is already ten to fifteen feet above the ocean.”

“But it's such a place for invalids!”

“Yes, it is a place for invalids. There are two kinds of people there—invalids and speculators. Thousands of people in the bleak North, and especially in the Northwest, cannot live in the winter anywhere else than in Florida. It's a great blessing to this country to have such a sanitarium. As I said, all it needs is building up, and then it wouldn't be so monotonous and malarious.”

“But I had such a different idea of it!”

“Well, your idea is probably right. You cannot do justice to a place by describing it literally. Most people are fascinated by Florida: the fact is that anything is preferable to our Northern climate from February to May.”

“And you didn't buy an orange plantation, or a town?”

“No; I was discouraged. Almost any one can have a town who will take a boat and go off somewhere with a surveyor, and make a map.”

The truth is—the present writer had it from Major Blifill, who runs a little steamboat upon one of the inland creeks where the alligator is still numerous enough to be an entertainment—that Mr. King was no doubt malarious himself when he sailed over Florida. Blifill says he offended a whole boatfull one day when they were sailing up the St. John's. Probably he was tired of water, and swamp and water, and scraggy trees and water. The captain was on the bow, expatiating to a crowd of listeners on the fertility of the soil and the salubrity of the climate. He had himself bought a piece of ground away up there somewhere for two hundred dollars, cleared it up, and put in orange-trees, and thousands wouldn't buy it now. And Mr. King, who listened attentively, finally joined in with the questioners, and said, “Captain, what is the average price of land down in this part of Florida by the—gallon?”

They had come down to the booths, and Mrs. Benson was showing the artist the shells, piles of conchs, and other outlandish sea-fabrications in which it is said the roar of the ocean can be heard when they are hundreds of miles away from the sea. It was a pretty thought, Mr. Forbes said, and he admired the open shells that were painted on the inside—painted in bright blues and greens, with dabs of white sails and a lighthouse, or a boat with a bare-armed, resolute young woman in it, sending her bark spinning over waves mountain-high.

“Yes,” said the artist, “what cheerfulness those works of art will give to the little parlors up in the country, when they are set up with other shells on the what-not in the corner! These shells always used to remind me of missionaries and the cause of the heathen; but when I see them now I shall think of Atlantic City.”

“But the representative things here,” interrupted Irene, “are the photographs, the tintypes. To see them is just as good as staying here to see the people when they come.”

“Yes,” responded Mr. King, “I think art cannot go much further in this direction.”

If there were not miles of these show-cases of tintypes, there were at least acres of them. Occasionally an instantaneous photograph gave a lively picture of the beach, when the water was full of bathers-men, women, children, in the most extraordinary costumes for revealing or deforming the human figure—all tossing about in the surf. But most of the pictures were taken on dry land, of single persons, couples, and groups in their bathing suits. Perhaps such an extraordinary collection of humanity cannot be seen elsewhere in the world, such a uniformity of one depressing type reduced to its last analysis by the sea-toilet. Sometimes it was a young man and a maiden, handed down to posterity in dresses that would have caused their arrest in the street, sentimentally reclining on a canvas rock. Again it was a maiden with flowing hair, raised hands clasped, eyes upturned, on top of a crag, at the base of which the waves were breaking in foam. Or it was the same stalwart maiden, or another as good, in a boat which stood on end, pulling through the surf with one oar, and dragging a drowning man (in a bathing suit also) into the boat with her free hand. The legend was, “Saved.” There never was such heroism exhibited by young women before, with such raiment, as was shown in these rare works of art.

As they walked back to the hotel through a sandy avenue lined with jig-saw architecture, Miss Benson pointed out to them some things that she said had touched her a good deal. In the patches of sand before each house there was generally an oblong little mound set about with a rim of stones, or, when something more artistic could be afforded, with shells. On each of these little graves was a flower, a sickly geranium, or a humble marigold, or some other floral token of affection.

Mr. Forbes said he never was at a watering-place before where they buried the summer boarders in the front yard. Mrs. Benson didn't like joking on such subjects, and Mr. King turned the direction of the conversation by remarking that these seeming trifles were really of much account in these days, and he took from his pocket a copy of the city newspaper, 'The Summer Sea-Song,' and read some of the leading items: “S., our eye is on you.” “The Slopers have come to their cottage on Q Street, and come to stay.” “Mr. E. P. Borum has painted his front steps.” “Mr. Diffendorfer's marigold is on the blow.” And so on, and so on. This was probably the marigold mentioned that they were looking at.

The most vivid impression, however, made upon the visitor in this walk was that of paint. It seemed unreal that there could be so much paint in the world and so many swearing colors. But it ceased to be a dream, and they were taken back into the hard, practical world, when, as they turned the corner, Irene pointed out her favorite sign:

Silas Lapham, mineral paint.

Branch Office.

The artist said, a couple of days after this morning, that he had enough of it. “Of course,” he added, “it is a great pleasure to me to sit and talk with Mrs. Benson, while you and that pretty girl walk up and down the piazza all the evening; but I'm easily satisfied, and two evenings did for me.”

So that, much as Mr. King was charmed with Atlantic City, and much as he regretted not awaiting the arrival of the originals of the tintypes, he gave in to the restlessness of the artist for other scenes; but not before he had impressed Mrs. Benson with a notion of the delights of Newport in July.

The view of the Catskills from a certain hospitable mansion on the east side of the Hudson is better than any mew from those delectable hills. The artist said so one morning late in June, and Mr. King agreed with him, as a matter of fact, but would have no philosophizing about it, as that anticipation is always better than realization; and when Mr. Forbes went on to say that climbing a mountain was a good deal like marriage—the world was likely to look a little flat once that cerulean height was attained—Mr. King only remarked that that was a low view to take of the subject, but he would confess that it was unreasonable to expect that any rational object could fulfill, or even approach, the promise held out by such an exquisite prospect as that before them.

The friends were standing where the Catskill hills lay before them in echelon towards the river, the ridges lapping over each other and receding in the distance, a gradation of lines most artistically drawn, still further refined by shades of violet, which always have the effect upon the contemplative mind of either religious exaltation or the kindling of a sentiment which is in the young akin to the emotion of love. While the artist was making some memoranda of these outlines, and Mr. King was drawing I know not what auguries of hope from these purple heights, a young lady seated upon a rock near by—a young lady just stepping over the border-line of womanhood—had her eyes also fixed upon those dreamy distances, with that look we all know so well, betraying that shy expectancy of life which is unconfessed, that tendency to maidenly reverie which it were cruel to interpret literally. At the moment she is more interesting than the Catskills—the brown hair, the large eyes unconscious of anything but the most natural emotion, the shapely waist just beginning to respond to the call of the future—it is a pity that we shall never see her again, and that she has nothing whatever to do with our journey. She also will have her romance; fate will meet her in the way some day, and set her pure heart wildly beating, and she will know what those purple distances mean. Happiness, tragedy, anguish—who can tell what is in store for her? I cannot but feel profound sadness at meeting her in this casual way and never seeing her again. Who says that the world is not full of romance and pathos and regret as we go our daily way in it? You meet her at a railway station; there is the flutter of a veil, the gleam of a scarlet bird, the lifting of a pair of eyes—she is gone; she is entering a drawing-room, and stops a moment and turns away; she is looking from a window as you pass—it is only a glance out of eternity; she stands for a second upon a rock looking seaward; she passes you at the church door—is that all? It is discovered that instantaneous photographs can be taken. They are taken all the time; some of them are never developed, but I suppose these impressions are all there on the sensitive plate, and that the plate is permanently affected by the impressions. The pity of it is that the world is so full of these undeveloped knowledges of people worth knowing and friendships worth making.

The comfort of leaving same things to the imagination was impressed upon our travelers when they left the narrow-gauge railway at the mountain station, and identified themselves with other tourists by entering a two-horse wagon to be dragged wearily up the hill through the woods. The ascent would be more tolerable if any vistas were cut in the forest to give views by the way; as it was, the monotony of the pull upward was only relieved by the society of the passengers. There were two bright little girls off for a holiday with their Western uncle, a big, good-natured man with a diamond breast-pin, and his voluble son, a lad about the age of his little cousins, whom he constantly pestered by his rude and dominating behavior. The boy was a product which it is the despair of all Europe to produce, and our travelers had great delight in him as an epitome of American “smartness.” He led all the conversation, had confident opinions about everything, easily put down his deferential papa, and pleased the other passengers by his self-sufficient, know-it-all air. To a boy who had traveled in California and seen the Alps it was not to be expected that this humble mountain could afford much entertainment, and he did not attempt to conceal his contempt for it. When the stage reached the Rip Van Winkle House, half-way, the shy schoolgirls were for indulging a little sentiment over the old legend, but the boy, who concealed his ignorance of the Irving romance until his cousins had prattled the outlines of it, was not to be taken in by any such chaff, and though he was a little staggered by Rip's own cottage, and by the sight of the cave above it which is labeled as the very spot where the vagabond took his long nap, he attempted to bully the attendant and drink-mixer in the hut, and openly flaunted his incredulity until the bar-tender showed him a long bunch of Rip's hair, which hung like a scalp on a nail, and the rusty barrel and stock of the musket. The cabin is, indeed, full of old guns, pistols, locks of hair, buttons, cartridge-boxes, bullets, knives, and other undoubted relics of Rip and the Revolution. This cabin, with its facilities for slaking thirst on a hot day, which Rip would have appreciated, over a hundred years old according to information to be obtained on the spot, is really of unknown antiquity, the old boards and timber of which it is constructed having been brought down from the Mountain House some forty years ago.

The old Mountain House, standing upon its ledge of rock, from which one looks down upon a map of a considerable portion of New York and New England, with the lake in the rear, and heights on each side that offer charming walks to those who have in contemplation views of nature or of matrimony, has somewhat lost its importance since the vast Catskill region has come to the knowledge of the world. A generation ago it was the centre of attraction, and it was understood that going to the Catskills was going there. Generations of searchers after immortality have chiseled their names in the rock platform, and one who sits there now falls to musing on the vanity of human nature and the transitoriness of fashion. Now New York has found that it has very convenient to it a great mountain pleasure-ground; railways and excellent roads have pierced it, the varied beauties of rocks, ravines, and charming retreats are revealed, excellent hotels capable of entertaining a thousand guests are planted on heights and slopes commanding mountain as well as lowland prospects, great and small boarding-houses cluster in the high valleys and on the hillsides, and cottages more thickly every year dot the wild region. Year by year these accommodations will increase, new roads around the gorges will open more enchanting views, and it is not improbable that the species of American known as the “summer boarder” will have his highest development and apotheosis in these mountains.